HOUSEHOLDS

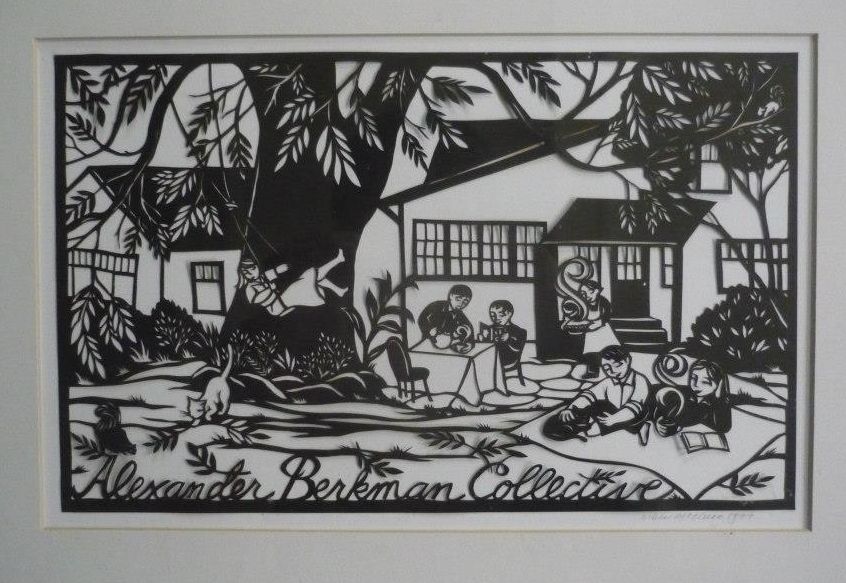

Alexander Berkman Collective

Becomes Black Walnut Association Land Trust

1974 – 76

By Susan Davenport

My neighbor and I decided to find a place to live together as newly enrolled students at the Evergreen State College. I’d already been to Olympia as a delivery person for the Little Bread Company of the Seattle Worker’s Brigade and loved the small-town feel. I had lived on Capitol Hill in Seattle for a couple years. My neighbor, Tessa Martinez happened to know my partner, Raoul Montoya. They went to the same high school at Los Alamos, New Mexico. Weird coincidence. Tessa’s roommate was a member of a women’s plumbing collective, a group allied with the Brigade.

Tess and I made a couple trips to Olympia looking at places. Olympia was semi-rural as close as two miles out of the Westside and Evergreen was essentially in the woods. We were interviewed by some landlords and potential housemates that just didn’t click for either of us. Our last stop was one recommended by Don Martin who knew a household that was having an exodus of roommates. They would have openings. It was Alexander Berkman Collective, “sister house” to the Emma Goldman Collective. I worked with Don at the Cooperating Community Grains warehouse, also part of the Seattle Worker’s Brigade, when he was interning there from Evergreen. Don lived at Emma Goldman and would also help found the Hard Rain Printing Collective that initially moved their equipment into the garage of the Alexander Berkman house.

Tess and I pulled up to of the Sherman Street address which had an attractive arch of tree limbs across the driveway. There was a big set of concrete stairs leading to an impressive 1920s vintage Craftsman-style covered porch. A tall, bearded man came out onto the porch limping, with a big boot on his foot. We introduced ourselves and why we were there. He welcomed us and apologized for not being able to give us a full tour of the house because he couldn’t get up the stairs. People were carrying things out of the rooms upstairs. The roommates laboring in the background did not engage with us and I sensed tension thick in the house.

Our interviewer was William Knowles. He vaguely mentioned the household had fallen apart due to internal conflicts, and that some did not want to purchase the home as a group, which was his intention and hope. We came to learn later that he was a brilliant, most challenging, charismatic personality. An intellectual labor activist and carpenter. He held the lease. We chatted and it was not more than twenty minutes before he asked us when we could move in. That was August 1974 and school started in September, so we were in by the first of the month.

Tess, Bill, and I selected the rest of the roommates. Household culture was to interview potential housemates as a group and decide as a group who was selected. It was a fun process mostly because each of the applicants that we interviewed we liked. It was a big house and we ended up accepting John Day, an instructor with Outward Bound; Tom Clingman, raised in a cooperative community in California; Kathy Haviland, a working-class woman from Shoreline; and Nancer Lemoins, a wild artist. Not long after, Nancer moved out and Lanny Aronoff, a true New Yorker, joined us.

The collective bonded as a group over the idea of buying the house. We accomplished that in our second year of living together. It was a beautiful, exceptionally well-built home on four city lots that made the back yard the size of a small park. Bill had leased it from the Sisters of Providence who once used it as a priory next to the old Saint Peter Hospital across the street. Bill was negotiating a purchase price of $35,000 which we all knew was a deal we could not pass up.

Our collective household somehow got the confidence to move forward and buy the house. It seemed we got along well, worked together well, were strong enough as individuals and as a group to overcome Bill’s sometimes overpowering personality. True to the 1970s radical culture in the spirit of political correctness, there was some intense calling one another to account. We navigated school, work, and relationships, even as some intense disagreements arose. Mutual support for each other got us through deep emotional experiences, our community involvement, and shared political activism. We cooked and ate together, tried experiments in shared (platonic) sleeping quarters, and worked on the house and its beautiful yard.

I had grown up in a cooperative community of which my parents were founding members. My mother, Elaine (Davenport) Stannard, was also a proponent of the community land trust model of the Institute for Community Economics, described by Paul Swann, a progressive economist. My mother shared bylaws of the May Valley Cooperative as an example and some seminal writing by Paul Swann. She directed us to the Evergreen Land Trust in Seattle as another model of ownership. Tom Clingman, who had also lived in a cooperative in Grass Valley, California, researched other land trust models as well.

Bill and Tom set out to find a bank that would give us a mortgage. We were expecting a challenge given our unusual approach of purchase by a non-profit – with no track record – and our limited incomes (we were all students except Bill.) But after the second bank turned us down, we realized our challenge was the old age of the house, not the young age of the purchasers. Old houses were not attractive to banks. Areas of Olympia that are now “historic districts” with restrictive design standards were zoned for “redevelopment” into multifamily structures. (Look at the scattering of apartment buildings in the otherwise-historic Bigelow neighborhood.) We found a much more welcoming attitude at Olympia Federal Savings and Loan, where we obtained a mortgage to purchase the house from the Sisters of Charity. The price of $35,000 was undoubtedly attractive to Oly Federal.

The first name proposed was the Red Cedar Land Trust. We soon all agreed to change it to the Black Walnut Association Land Trust in honor of the gorgeous ancient tree overarching the back yard.

We had so many conversations about the vision, mission, purpose, and operating bylaws. I enlisted pro-bono help to review our incorporating documents from an attorney who was a neighbor. Turned out he was a very conservative Republican, but he liked the idea of the community land trust. Each of us ponied up what we could for the down payment and used a local bank, Olympia Federal, as our mortgagee. They held the portfolio and were willing to do this because of the intrinsic value of the house and property. The incorporating documents sit in Secretary of State nonprofit records under the Black Walnut Association Land Trust for anyone who is interested.

Shared work on our shared home was joyful. As a group, we enjoyed the “fruits of our labor” with the intention of sharing the space with our community. ABC House, as it has come to be known, has housed many people, supports meetings of many activist groups, and still serves as a petri dish for social experimentation and plain fun as a venue for gatherings, music, and other performances. It is the peoples’ resource created by our labor, combined finances, and a shared vision.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer

Sixth paragraph: Bill had a lease-option from the Sisters of Charity. It stipulated a purchase price of $35,000.

Next to last paragraph, I would like to offer a bit on our search for a mortgage for the Alex house. It had a twist that says something about the character of the Olympia institutions in those days. Something along these lines:

Bill and Tom set out to find a bank that would give us a mortgage. We were expecting a challenge given our unusual approach of purchase by a non-profit – with no track record – and our limited incomes (we were all students except Bill.) But after the second bank turned us down, we realized our challenge was the old age of the house, not the young age of the purchasers. Old houses were not attractive to banks. Areas of Olympia that are now “historic districts” with restrictive design standards were zoned for “redevelopment” into multifamily structures. (Look at the scattering of apartment buildings in the otherwise-historic Bigelow neighborhood.) We found a much more welcoming attitude at Olympia Federal Savings and Loan, where we obtained a mortgage to purchase the house from the Sisters of Charity. The price of $35,000 was undoubtedly attractive to Oly Federal.