FIRST PEOPLES

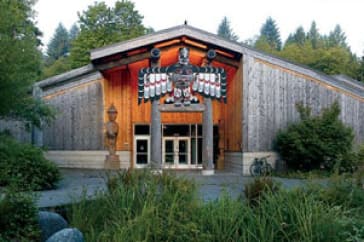

The Evergreen Longhouse – A Prehistory

How I Got to Fulfill My Last Assignment from Mary Ellen Hillaire,

The Evergreen State College Campus Came to Fund a Longhouse,

To See It Built, and Open It In 1995

By Colleen Jollie

Turtle Mountain Chippewa

In 2020, as we celebrated the twenty-five year history of The Evergreen State College Longhouse, the House of Welcome, I was aware that my historic perspective might be more of a creation story or a pre-history. There was certainly a lot of magic that fueled the creative process to make this event possible. For me this story began when I entered Mary Ellen Hillaire’s program at Evergreen to continue my work as a student of Northwest Coast Indian Art and Architecture in 1975. Before I came to Evergreen, I was already deeply involved in a project to build a tribal facility in the form of a traditional style longhouse for the Nisqually Indian tribe.

My involvement in building a longhouse on campus lasted from 1975 until we opened what was then called the Longhouse Education and Research Center in September of 1995. When the Longhouse opened, the original office had several computer hookups the college gave us to serve as an internet research lab that students could use. After the legislature passed the budget that funded the building of the Longhouse, I became the project coordinator during design and construction, and oversaw the first quarter of operation during its opening year.

When I first showed up in Mary Ellen Hillaire’s office, I had recently graduated from Fort Steilacoom Community College where I had begun my study of Northwest Coast Native art, a topic I loved. Studying that topic at Fort Steilacoom was not always easy. When I proposed to carve a Native Northwest-style mask as an art project for an upcoming quarter, my art professor told me that Northwest carving was “just folk art, not real art.” Clearly, he was trying to discourage me from learning both the technical skills and the design skills I needed in order to understand the complexities of Northwest Coast Native art, and he lacked the knowledge, interest, or skills to teach me.

Since I knew nothing about carving, or the traditional tools used, and had no teacher, I produced a clumsy attempt at a moon mask and ended up with Band-Aids on every finger. I knew I had to do what I could to transform the way people taught courses on Native art at the community college. Before I left Fort Steilacoom, I put together an independent project, a weeklong art event featuring historic Northwest Native art, active art demonstrations, and a multi-media juried show. I invited my art professor to be one of the judges along with my boss, Del McBride, from the State Capitol Museum, and my anthropology professor. It had the desired effect on my art professor as he learned more about this magnificent cultural form.

In January of 1976, I was a student at The Evergreen State College (TESC), and I was required to keep a journal that would become part of my evaluation at the end of the quarter. My first journal entry declared, “I am now part of a notorious group known as the Evergreen student body.” At Evergreen we were committed to doing interdisciplinary studies and my responsibilities as a student in the Native American Studies Program centered on three overlapping areas: I served as the museum planner for the Nisqually Tribe; I concurrently worked as museum assistant at the State Capitol Museum; and I attended program activities on campus where I was encouraged to develop curriculum and projects that helped me to learn about longhouses, smokehouses, pit houses, and other traditional Indigenous architecture and art with Mary Ellen Hillaire. My work in the Native American Studies Program allowed me to continue work I had started doing at Fort Steilacoom Community College, combining resources in the community with academic courses. But at TESC I could combine the work in the community with work overseen by a Native faculty from the Lummi Nation who had real expertise and an interest in the information I wanted to learn. Who could imagine that I would find a program anywhere that would let me specialize in developing skills seldom taught in American colleges? At Evergreen I was encouraged to create a curriculum that would allow me to learn and do things that deeply mattered to me.

When I began my work with Mary Ellen Hillaire, she asked me the four questions she asked every student with whom she worked. She expected us to formulate our work by answering: “1) What do I want to do? 2) How do I want to do it? 3) What do I want to learn? 4) What difference does it make?” These questions drove Mary Ellen’s students to define work that was meaningful to them and to try to make a real difference in the world. At the end of each quarter I reflected on what I did and evaluated my work. In her office, Mary Ellen had placards on her walls that identified her as a different kind of teacher. Looking around, one could read, “Bloom Where You Are Planted” or “You Have Touched Me—I Have Grown.” She told me, “We are all teachers and learners here.” She was welcoming and hospitable which felt reassuring and encouraging. At the time, I was not a young student right out of high school. At the age of twenty-nine, I was a seasoned civil rights activist and a single mother with a six-year-old daughter. I needed to get my degree and to get to work.

In the Native American Studies Program, I learned first hand that Native students needed a hospitable learning environment, and Native arts deserved “real” recognition. I was personally determined to promote Native art at every opportunity. Mary Ellen Hillaire taught me about both personal authority and mutually-shared authority. From her I learned lessons about issues of identity, self-knowledge, self-control, and self-esteem. She taught each student to pursue their own aspirations. This “longhouse philosophy” taught me the guiding principles I would need as I dedicated myself to what she called “lifelong learning.” I would need and rely on these principles many years later when I returned to TESC for my graduate degree and came to focus my thesis on the Longhouse that still had not been built on campus.

Certainly, my education at Evergreen during the 1970s prepared me for the graduate work I would do during the 1990s. When I first came to Evergreen, I was working at Nisqually with Chairwoman Zelma McCloud, Historian Cecilia Carpenter, and Councilman George Kalama. Assigned to the planning department, I was asked to develop a community center that would start with building a longhouse, then a restaurant, and finally a tribal museum. I knew nothing about any of these things and was just beginning to learn to write grants, to plan projects, and to get stuff done. During this time, I worked with a young man named Joe Cushman who told me that none of the planning courses he took at the University of Washington in Seattle had prepared him for this job, so I didn’t feel bad about the fact I was doing on-the-job training. Doing this job, Joe and I learned how to procure funds to purchase land on the Nisqually Reservation so the tribe could build their first tribal administration building, a smoke shop, and HUD housing. I also learned to collect materials to build the Nisqually Longhouse from logging companies around the area using a cutting list I made from my plans. After I graduated from Evergreen, I resigned my position with the Tribe in the spring of 1978, and I transferred my responsibilities to the new head of the Nisqually planning department.

Mary Ellen talked the administration at TESC into letting her hire me as an adjunct faculty. When I was her student, she had immediately developed an interest in what I was doing at Nisqually building a longhouse for the Tribe to use, and wanted to build a longhouse to use as an educational facility for Native American Studies at Evergreen. She asked me to focus my work on developing a proposal for building a longhouse on campus. Mary Ellen and I traveled together across the state to smokehouse activities and community events. We discussed our plans with people in various Indigenous communities and then with students when we returned. I was happily working with a kindred spirit. She clearly wanted the Longhouse to be a modern college facility that would be second to none. As she put it, she didn’t want “a little outhouse.”

I researched longhouses, drew on my work with the Nisqually Tribe, and drafted a proposal. I developed presentations and exhibits, and I wrote a letter to Dan Evans who was then the president of the college to invite his participation in our development process. Mary Ellen and I met with him, and he created a special fund for the Longhouse, putting one thousand dollars from his discretionary budget for planning into it. It seemed we had his support for the project. I would later learn, however, that the usual way to get the college to fund a new facility was to get it in the capital budget through the state legislature. Indeed, I had no idea how to convince the college to fund the building of a longhouse educational facility until I learned the funding process as a graduate student in the Master of Public Administration program in 1992.

In retrospect after reading all the documents and interviewing the stakeholders, I realized several administrators were not interested in using state funds to build a longhouse, and a few did not understand the value of designing educational programs that supported the needs of the Indigenous Nations until years later. Mary Ellen had a vision about what the Indian community needed, and she had the support of a small group of faculty colleagues and a number of Native and non-Native students, but it took years of struggle to make others appreciate the value of having a longhouse on campus. Before it was built, only a few of the administrators and faculty understood that the Longhouse could become a focus for programs serving the educational needs of Native American people.

At the end of the 1978 – 79 school year, the college ended funding for my position and I found another job. A few years later, I was surprised by a visit from Del McBride, my former boss at the State Capitol Museum, and Mary Ellen Hillaire. I was excited to see them, but Mary Ellen had bad news. She told me she had cancer and was not long for this world, and she was busy giving out assignments. She said, “If the Longhouse is going to get built, it will be up to you.” I assured her I would do whatever I could. It was a promise I meant but, at that time, I had no idea what I could do that had not already been tried. I was working as a counselor at a local business college interviewing thousands of students. When there were Native students among them, I would tell them about Evergreen’s Native Studies Program and the plans to build a longhouse on the campus.

Mary Ellen continued to work on the project as much as she could until she died in October 1982. For the next decade, students, faculty, and the greater Native community continued to put approximately a thousand dollars a year into a special fund that Dan Evans had started for the Longhouse. As a result, the idea for a TESC Longhouse gained traction as others worked to keep Mary Ellen Hillaire’s vision alive. During this period, the yearly dinners at the Squaxin Island gymnasium and Tribal office were held by David Whitener Sr., Chairman of the Squaxin Tribe who was also a faculty member in the Native American Studies Program at TESC. Dave worked hard to keep the dream of the Longhouse alive, and invited his friends John and Edie Hottowe and Hamilton and Mary Green from the Makah Nation in Neah Bay to be masters of ceremony at these events. There was always a blanket dance to raise money for the Longhouse. Because of Dave’s commitment, students from campus and members of the Native American community continued to support Mary Ellen Hillaire’s vision of a longhouse on campus throughout the 1980s.

In 1990, I returned to TESC and enrolled in the graduate program in Public Administration to earn my master’s degree. When I got back to campus, I asked, “Where is the Longhouse?” I fully expected to see it somewhere and was curious to know how it had progressed. I quickly discovered that the Longhouse project was dormant. A report had been written that stated, “The vision of the Longhouse was blurred, and it should be dropped.” Clearly when it came to the Longhouse the college bureaucracy had become infected with a case of “governmentium,” that absurd scientific element that can make any project inert. It was discouraging news.

The graduate program curriculum was rigorous, and I worked hard to gain the skills I would need to be an effective public administrator. Lucia Harrison, the MPA director, knew I was disappointed that no Longhouse Educational Center had been built. When it was time to produce my master’s thesis, she suggested that doing it on the Longhouse project might produce positive results. Initially I resisted. I wanted to focus my work on something that might have a chance to succeed. Director Harrison, who wanted to see the Longhouse built, said she wanted me to try “one more time” (a phrase Mary Ellen used to say) and I remembered my commitment to her. We signed up two more students for the Longhouse Team, Judith Brainerd and Lawanna Bradley, whose name has since become Bonnie Sanchez. To her credit as an MPA student, Lawanna drove from the Quinault Reservation in Taholah to Evergreen twice a week for two years for evening classes—a two-hour commute each way which she did after working all day.

The three of us studied action research, agenda setting, women’s leadership, and a particularly revealing process whereby projects needed by minority groups are handed off to those groups to make them happen once it is discovered how expensive they will be. We dug through the Longhouse history files. We found that the Longhouse had never been put on the Capital Facilities Agenda that mapped out the master plan and priorities for campus development, and so it had never had a chance to be part of the list of capital projects submitted to the state legislature for funding. We also learned there was very real administrative resistance to asking the state to fund the Longhouse project on campus.

In addition to the demands we held in common—all the research, the literature review, digging through historic files, plus our weekly meetings to share and compare notes—we divided up important tasks so we could complete our work on time. We created a questionnaire survey instrument. It became my job to interview past stakeholders, faculty, students, and community members, and to delineate the story. I captured the oral history of the Longhouse by asking detailed questions of stakeholders who had information about the obstacles that had blocked the project and who could share their ideas about how those obstacles could be dismantled. I had a brand-new tape recorder and taped everything that people were willing to say on the record. But every so often my tape recorder would short out and shut itself off. That’s then the stories would come out about the subtle resistance to the project. I listened. I would shake the tape recorder and it would magically start taping again and the tenor of the conversations changed back. In that way, the complexities of the story were voiced and heard. This information helped us to formulate strategies to successfully argue the case for funding.

Judith Brainerd was our terrifically talented writer. She worked at the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries as the administrative assistant to the Secretary during the day, a demanding job. At night she crunched massive amounts of notes and transcribed stories that I had collected into our thesis document. At the same time, we were all reading volumes of literature on the subject of public administration. At the end of this process, we published our findings in our master’s thesis, The Gatekeepers: The Longhouse Project at The Evergreen State College.

When we defended our thesis, we chose to be first on the review committee’s agenda. We incorporated art and music into our presentation, a strategy that Native American Studies faculty member David Whitener suggested when I interviewed him. He told me, “Be like Spider Woman creating the world with a song.” We acquired two traditional Makah songs from Native culture keeper John Hottowe, who gave us the Dog Spirit song and a love song that had come to him for one of Dave Whitener’s Longhouse dinners. As talented as Judith was in writing, Lawanna had equal measure in music. She played piano and guitar and sang beautifully, in fact, she had softened our intense study sessions with her music on several occasions. She opened our thesis presentation with the first stanza of a song called Love Can Build a Bridge by The Judds. Judith followed with the framework of our thesis. I recounted the stories from stakeholders. Lawanna closed with the last stanza of the song. There wasn’t a dry eye in the audience, we emotionally moved everyone who listened. Lawanna had heard that particular song by the Judds sung by Maori travelers from New Zealand when they visited the Quinault Indian Nation on a tour to connect with Indigenous people of the Pacific Rim. (It is also worth noting that the Maori connections to the Longhouse have become stronger over the years.)

Our defense presentation was a success, incorporating not only scholarship and our findings, but also history, music, and art. We designed matching sweatshirts and had them imprinted with what would become the Longhouse logo. Having successfully completed our thesis, together, we marched in the 1992 commencement ceremonies. To decompress after commencement was over, I drove for three days with my sister all the way to the reservation of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians in the middle of North Dakota to visit our family. I am a descendant of the Tribe. I felt like I had been shot from a gun.

When I returned to Washington, I received a call from Dr. Thomas L. “Les” Purce, acting president of the college at that time. He called me in for a meeting with Jon Collier, the campus architect, to discuss possible locations for the Longhouse. Because many Salish villages were built on inlets of what was then still called Puget Sound and is now called the Salish Sea, there were some people who wanted the building located on a relatively undeveloped part of the campus on Eld Inlet which was a long way from the rest of the campus. As a result, the location of the building had been one of the biggest obstacles.

I had already envisioned where the Longhouse should be. One day when I was having lunch upstairs at the student union, I looked out the window. I could see past the library, down that drum-roll of trees to the space at the far end of the walk. And there it was, the Longhouse, looking right back at me. I almost choked. After lunch, I ran to the model of the campus kept on the fourth floor of the library. There was a space reserved in the campus master plan for classrooms on Dogtooth Lane, located near where the dog kennels used to be. The area on Dogtooth Lane had all the stub-outs for utilities. John Hottowe’s Dog Spirit song was opening the way. It also turned out there was standing water adjacent to the site that could be turned into a small brook and channeled into a waterway to join Eld Inlet. When we met, Jon Collier said that was where he wanted to build the Longhouse. Both of us came to the same conclusion about where to build. President Purce said, “Well, let’s do it!” His booming voice and laughter sparked my joy and confidence that this time we could do it.

President Purce asked if we could repeat our thesis presentation for the TESC Board of Trustees. It became clear to me that he wanted to see a longhouse built on the campus. Lawanna had to work, but Dave Whitener, Judith, and I made the presentation with John Hottowe’s songs playing in the background. When it was pointed out that the college had a $13,000 fund and had been collecting donations for 13 years but that the building had never been listed on the capital facilities plan, not even at the bottom of the agenda, there was a pregnant pause, and the Board of Trustees directed that the Longhouse be made part of the college’s capital budget request. Lucia Harrison was right: the agenda was set.

Later in the summer of 1992, Jane Jervis was hired as president of college. She attended her first budget meeting and noticed that the Longhouse was part of the capital budget request for the next biennium, but it was down on the list after the repair of the roofs. She insisted the Longhouse be moved to the number one spot on the list, and the trustees agreed. President Jervis gave Dr. Purce, now executive vice president for finance and administration, the task of getting the funding for the project from the state legislature.

Dr. Purce insisted that I be hired to help with the legislative process. I worked with the college graphics department to design a brochure, and then lined up Native speakers to give endorsements while documenting widespread support. By this time, many legislative staff members, and even some legislators, knew about the Longhouse and had made personal contributions over the years. People wanted to see it happen. I will never forget that sine die when the legislature adjourned in 1993, and the Longhouse had been given $2.2 million dollars as part of the governor’s budget. On a hunch, I called my voicemail at work. There were five or six messages, all left by people who were at the signing—they were letting me know that we got the funding! I sat down and cried like a baby.

Now that there was real money involved, everyone had an opinion. We had to design and build the Longhouse in one biennium—two years. I remember, when we started the design process, my boss, Interim Academic Vice President and Provost Russ Lidmann, told me to “go see what other colleges have done, we don’t have to invent one.” I did not have the heart to tell him what I already knew, that in fact we were about to design the first such facility on a college campus in the United States. We had to quickly convene a rock-solid planning committee. Every member brought something special to the work from across a broad spectrum of interests. Dave Whitener, NAS convener, had kept the dream alive with the patience of a Native fisherman. Jon Collier brought his expertise as the campus architect. Del McBride, Cowlitz/Nisqually artist and retired museum curator joined the team, as did Mary Ellen Hillaire’s sister, historian Pauline Hillaire, who possessed the strong cultural knowledge of the Lummi Nation. Sid White, a founding TESC faculty member who ran the college art gallery, a gentleman and a scholar, represented the college staff and faculty. John and Edie Hottowe brought the voice of tribal elders and culture keepers from the Makah Nation. Staff members from the facilities department participated so they could remind us of the practical side of managing a building.

We immediately worked on describing the architectural program by defining what we wanted to do in the building. We thought about how many square feet we needed and how that space could be structured. The committee hired Jones and Jones—architects, landscape architects, and planners—led by Johnpaul Jones, a Choctaw man and a true visionary. We met, held public meetings, and gathered input. After these meetings, Johnpaul would go back to his office and return with drawings that captured the ideas we discussed. He illustrated solutions and delivered what would become an award-winning design.

In what was perhaps our most difficult meeting, we had to decide about fireplaces. There must have been thirty or so people in attendance. Fire, a symbol for learning, was a main element in traditional Salish longhouses (also known as smokehouses). The problem was the smoke. Many people on the TESC campus are sensitive to air pollutants, fragrances and the like, and several of them were in that meeting. The discussion became intense, with people talking over each other. To facilitate the discussion, we decided on a longhouse procedure of taking turns talking and listening. Faculty member Rainer Haasenstab had a feather in his wallet that we used in place of a talking stick. Each participant weighed in with their concerns. People spoke with care and listened with equal care.

Pauline Hillaire encouraged me during the stressful times. “Trust in the culture, Colleen, it will always support you.” Her advice has served me well in many situations. The Longhouse was already doing its work. The fireplace discussion took what felt like forever, but in the end, we built three fire pits: one would use natural gas in the center of the Welcome Hall; the second would be a circular image, a symbol of a firepit; and the third would burn actual wood in what was becoming the most traditional room of the building, the Cedar Room. I carved Mary Ellen Hillaire’s initials into the concrete of that firepit in the Cedar Room the day it was cast: MEH, my dear friend and colleague.

The design team met regularly throughout the process, and reported back to the greater community, to the students, and to the Board of Trustees. It was a thrill to participate as the committee went from conversations about vague concepts and ideas to well thought out plans about how we could use the building. From drawings to detailed designs and blueprints we could approve, from the placement of the large cedar logs that would make the building’s frame to a finished building we could stand inside. A place that would shelter us, where faculty could facilitate learning and students could do their work and learn. We designed a space where we could invite artists and activists from the Native communities and support intercultural activities. During that experience, I felt an actual change in my brain. Working on the Longhouse design was an art, the creative process actualized.

When the walkway was finally poured joining the Longhouse to the rest of the TESC campus, I went out the next morning to do my daily check and found a coyote footprint pressed into the walkway surface. According to John Hottowe, the dog or wolf spirit is a Creator in Northwest Native traditions. In the Cedar Room, their spirits are depicted on the woven cedar bark panels made by Tawana artist, Bruce Subiyay Miller, to honor their power. The Dog Spirit song came to me, and I felt like the Creator had put his signature right there, cast in concrete. Success!

When I finally attended the first Native American Studies Program meeting in the Cedar Room, with a fire burning, I fell asleep (swooned, actually). I went home and slept for three days. My assignment was delivered.

Going through my student journals, I found a question I had written twenty years previously when I was a museum intern considering modern uses of historic buildings: ‘How might a longhouse be used in a modern way?’ I had my answer now, and Mary Ellen had her “place of hospitality where Indians could come and study, not a place to study Indians,” and certainly, not an “out house.” The Longhouse was second to none; in fact, it was a first such building on a college campus in the nation. Now that the Longhouse, our “House of Welcome” was built it was clear we had forged a new path. Now it was time to officially open the Longhouse and invite people into the place of hospitality. We needed to celebrate.

In October 1994, the new Provost Barbara Leigh Smith set up a Longhouse Program Planning Disappearing Task Force (DTF) chaired by Masao Sugiyama. Many of the members of the DTF were Native faculty who had long advocated for a longhouse as well as staff from other areas of the college who would be involved in building and supporting it. I worked closely with Masao and wrote the final report.

The DTF was asked to address three major issues: 1) guidelines for future programming and relations to other campus services and cultural events; 2) principles of shared use for space management; and 3) planning for the opening and use of the Evans Chair including appropriate Evans Chair scholars. The DTF recommended that a permanent program manager be hired for the Longhouse and that an advisory board be established to provide guidance and representation. Programmatic recommendations included supporting all Native programs at Evergreen, developing Native connections to Evergreen’s three graduate programs, connecting to other external Native cultural groups and organizations, and providing funds for Native students (i.e. scholarships, special needs, student originated studies and individual contracts).

I was given a three hundred dollar budget to plan the grand opening celebration. Clearly the budget was too small. I decided to get creative. We had enough money to print t-shirts with the same Longhouse design (the one we printed on the sweatshirts we made to wear at our thesis defense for the MPA program). I sold t-shirts at every special event all summer. I consulted with friends in the Indian community as we planned and they supported the event. The Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission gave us salmon. Mel Moon secured several five-gallon buckets of berries from his parent’s berry farm in Puyallup. Others gave us bushels of fresh corn. We had clams gifted to us. I don’t remember where the potatoes came from. Dave Whitener hired a tribal cook. Even businesses in the area helped. Costco gave us paper plates and utensils. We fed three thousand people that day. People opened the Longhouse properly and state and local officials spoke. Bruce Subiyay Miller’s Twana drum group filled the house with traditional prayers, music, and dances. Governor Mike Lowery addressed the crowd. Buffy Sainte-Marie gave us a concert. Attracted by what we were doing, above the building eagles circled overhead. It was a party, a potlatch, a sacred moment.

The opening of the Longhouse in 1995 coincided with the launch of the Evans Chair scholar program started to honor Daniel J. Evans, former three-term Washington State Governor, former U.S. Senator, and past president at The Evergreen State College. A committee was formed that included several Native faculty members, and it was given the money set aside to pay the salary of a visiting scholar to teach or lecture at the college. Rather than hire a single scholar, it was decided that the committee should divide the money and hire a group of Indigenous scholars, making sure that the group was gender balanced and represented experts on Indigenous arts and culture from various age groups from young people to elders. Buffy Sainte-Marie—multi-talented, award-winning Cree musician, composer, artist, educator, television and film star—was part of that cohort and came to teach on campus for a short time. The other Evans Chair scholars who came to campus during 1995 included Billy Frank Jr.—Nisqually fishing rights activist, head of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission and a national leader protecting the environment, salmon, and Indian treaty rights; Vi Hilbert—Upper Skagit linguist, and University of Washington professor who was fluent in, and taught, Lushootseed Salish, wrote bilingual and Salish language books full of traditional stories, and founded the Lushootseed Research Center to keep the language alive; John Hottowe—Makah leader who preserved and taught the traditional ceremonial songs of his people, composed new songs in the Makah language and worked to preserve and teach his people about Makah culture; Hazel Pete—Chehalis founder of the Hazel Pete Institute of Chehalis Basketry who preserved and passed down the weaving traditions of her people; and Sherman Alexie—Spokane/Coeur d’Alene poet, novelist, screenwriter, and filmmaker, the youngest member of the group. These scholars made presentations to a variety of classes across the campus, to both Native and non-Native students in undergraduate and graduate programs in true interdisciplinary Evergreen style. As part of her residency, Buffy Sainte-Marie, besides giving the concert at the Longhouse opening, taught computer generated art and donated one of her large artworks as a gift to the Longhouse. That work is still on display in the building. This roster of superstars foretold a bright future for the Longhouse and the Evans Chair scholar program. It was certainly a high note upon which to complete my last assignment from Mary Ellen Hillaire who believed that Native people with traditional cultural knowledge who passed down Native values to other Indigenous people were important to keeping Native culture alive. She saw the kind of culture-based information they possessed as equivalent to any advanced academic degree.

As soon as we opened the Longhouse it was in constant use. Faculty taught regular Evergreen programs in Native American Studies and other disciplines there, and we used the facility to host the Evans Chair scholars. The initial major art event we held at the Longhouse was the first ever Northwest Native Basketweavers Gathering which was co-sponsored with the Washington State Arts Commission. It took place two weeks after the Longhouse opened. We had booked the event the previous winter, while snow was falling on the great house posts. At the time, it never occurred to me that we might miss the opening date, and we didn’t. We stayed on budget and on schedule, even though we had to re-advertise because the construction bids came in way over the budget. Some elements in the building plans had to be cut to bring the cost down, but when the time came, the basket weavers were able to meet.

That gathering of basket weavers would become a blessing to me. They gave me my next big challenge and became my friends for life. When they allowed me to become the founding executive director of the Northwest Native American Basketweavers Association (NNABA) I had a chance to put my graduate degree to work again. We held the second annual gathering of the association in the Longhouse in 1996. Twenty-five years later, approximately a thousand weavers still gather annually at this event as the venues are moved across the northwest region. Events have spread throughout the Northwest in a great circular motion, like a coiled basket. There is something beautiful about weavers teaching weavers to preserve and promote their art.

As coordinator of the Longhouse during that first year, I continually asked myself the question, “How can the Longhouse provide a public service to the Native nations in Washington State?” All of my studies about Native art led me to ask artists in the Indigenous communities what we could do to help. I wanted to create a hospitable place for Native artists to learn and teach. I got input from artists across the state. An artist from the Makah Nation wanted to see an art market at Christmastime that had the potential to support artists economically. I worked with John McCann in the provost’s office and we wrote a $322,000 grant proposal to the Northwest Area Foundation in partnership with the South Puget Intertribal Planning Agency (SPIPA), which was a partnership of six local tribes. The three-year Native Economic Development Arts grant would run from 1996 through 1999 and fund the Longhouse project coordinator. Five program components were also funded: annual Native art sales, mini-grants, an artist-in-residence program, and business and marketing services. After my success coordinating design, construction and operation of the Longhouse during its first year, I was eager to continue my career in public administration.

Over the years I have had several occasions to revisit the Longhouse. When I worked as the deputy director in the Governor’s Office of Indian Affairs, I witnessed the Longhouse doing its work as a meeting place for tribal chairs from the twenty nine federally-recognized tribes together along with Governor Gary Locke, and later Governor Christine Gregoire, for annual Centennial Accord meetings. Clearly, the Longhouse serves the Indigenous community in many ways, and I am very proud to have played an important part in making that happen. It has been a deeply satisfying part of my life working with Mary Ellen Hillaire, Lucia Harrison, Thomas “Les” Purce, David Whitener, Jane Jervis and others who saw what a valuable resource Evergreen’s House of Welcome would be. Still, given my love of Indian art, my favorite events will always be the winter art fairs, when I do my best Christmas shopping. It is so satisfying to be surrounded by people buying “real” art made by extremely talented Indigenous people and to know that the culture will live on because artists in the community will receive a direct economic benefit from the work they do.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer