ACTIVISM

Women’s Shelter and Support Services Task Force – 1975

By Susan Davenport

In 1975, one of the social spots for young adults and students was, oddly, the local Crisis Clinic. Many Evergreen and Saint Martin’s students who were looking for ways to connect in the Olympia community volunteered there. Word of mouth got around that they offered exceptional training in communication skills, crisis intervention, suicide prevention, and de-escalation of acute mental health episodes, along with expansive knowledge about local agencies, resources, contact numbers, and their eligibility criteria. This was a treasure trove for students in sociology and psychology studies and those interested in internships or social-issue policy work.

Another draw was that the founding executive director of the Crisis Clinic, Kathy McKinnon, was the designer and instructor of the training and an excellent mentor to young women who volunteered. She was a force to be reckoned with, who held her mentees to a high level of accountability. She taught grant writing, organizational development, and facilitation skills informally to those who sought out her guidance.

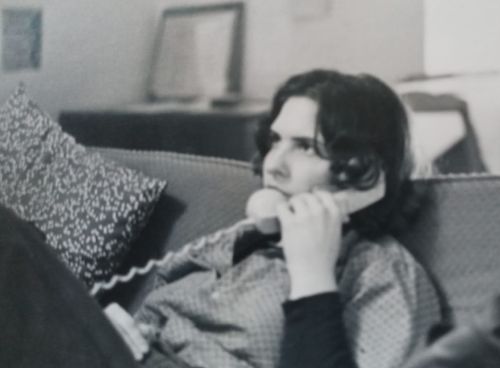

Two best friends, Colleen Spencer and I, decided to take the graveyard shift to have a weekly opportunity for a girls’ night sleepover in the midst of our work/school week. The Crisis Clinic had two twin beds adjacent to the phone room for resting during the night shift. Two people were required to take turns—one to be the awake and alert responder for calls. Not much rest or sleeping occurred for us as we talked the night away.

Kathy McKinnon came in one morning and asked us if we had ever responded to calls from battered women. Both Colleen and I had. She asked what we had done about this. We responded with the Crisis Clinic protocol we’d been taught: get her permission to call the police, get the address, put the woman on hold, call the police, and then get back to the woman to support her until the police got there. Sometimes we did follow-up calls on our next shift if the woman asked for this.

Kathy had just gotten through reading a book called Battered Wives based on research by J.J. Gayford. Another book had come out called Scream Quietly or the Neighbors Will Hear. There had also been a recent article about battered women in the New York Times. In the 1970s this was some of the first public examination of “wife abuse” as a social problem, brought to light by feminist activists. Battered women were essentially invisible up to now. Kathy knew this was an issue from our work on the phone lines. Colleen Spencer and I knew because we were both survivors of domestic violence and sexual assault.

Kathy gave us and the rest of the volunteers the assignment to log these calls with “women in crisis” under the new title “battered women” in our record book. One morning she came in after our overnight shift and showed us the total for eight weeks. She looked at us and asked simply, “Would you be interested in starting a women’s shelter for our community?” She said she knew without a doubt this was an essential service needed in our area, but she could not take on such a project and wanted to support us to do it.

Kathy, in her wisdom, encouraged us by laying out the first steps we would have to take to get established as a task force, and the type of supporting data we would have to collect to justify the need and apply for grants. To get us started, she handed us a grant application packet for a community needs assessment put out by the Law Enforcement Association of America. She also gave us guidance on how to write it. The FBI reported at that time that a quarter of all law enforcement fatalities were due to “domestic disturbances.” We were briefly put off by the idea of working with the FBI and law enforcement, but being pragmatic community activists, we forged on.

The justification for the grant was our experience at the Crisis Clinic. The grant was to pay for a comprehensive community needs assessment, including data from law enforcement, hospitals, doctors, dentists (tooth loss due to beatings), the community mental health center, the Department of Social and Health Services, and other agencies related to child and family services, such as Head Start.

In order to make ourselves viable to receive the grant we had to have an administrating body to accept the funds. Kathy couldn’t take this on, so she suggested we go to Ethel Roesch at the YWCA. Colleen and I had no experience with this type of ask. We went into the meeting raw and unpolished, speaking from the heart. Ethel was an old-school, refined, charitable agency administrator. She gave our young hippie student selves a once over, saying this was a “highly unusual request.” She also said “Yes” and gave us the attic in the YW building at Union and Franklin for an office.

Coincidentally, I was enrolled in the Community Advocacy program at Evergreen (1975-76) with faculty Russ Fox and Hap Freund. Our class assignment was to do a community needs assessment and write a fictional program proposal to meet this need. We were to form teams for this purpose. I presented the idea for our shelter project as “unformed and fitting the criteria for the assignment,” gathering other students to help with the needs assessment paid for by the grant.

Russ Fox was not pleased when he discovered my subterfuge. As an experienced community organizer, he knew what we were getting ourselves into and saw it as conflicting with the work he wanted from us in the academic program. It was not just a short term, one quarter, fictional assignment. It was the real deal, and our team would be committed to seeing it through on the twelve-month grant timeline. I got credit for the course, and a terse note in my evaluation about not following instructions for a one quarter project.

The women who chose to work with us were also all survivors of child abuse, sexual abuse, rape, or domestic violence. We were committed to seeing the shelter happen. We formed the Women’s Shelter and Support Services Task Force under the mentorship of Ethel Roesch at the YW with Kathy McKinnon in the background feeding us high-level community contacts essential for moving the project forward. Our team was Sarah Albertus, age 23; Lisa Pontoppidan, 19; Lauren Herbert, 19; Kathy Haviland, 21; Colleen Spencer, 21; and me Susan Davenport, 19. We embarked on an amazing journey, rowing upstream in 1970s provincial Thurston County to bring the issue of battering to light and accountability.

Our group did one-on-one contacts with community leaders to educate them on the issues. We did “dog and pony shows” to the local civic groups. We did additional grant research and examined models for shelter programs. We found one such program through Radical Women in Seattle. It was run by Coyote, a Portland-based prostitutes’ union. Colleen and I travelled to Portland to talk with representatives and attend their meeting about rape and violence against women. We looked at their “safe house” model that took women off the street and away from violent pimps. The women were sheltered in private homes in a network across the West that got them out of state and safe. We thought this might be a model for our project prior to finding a facility that would be the formal shelter.

Colleen and I kept our shift at the Crisis Clinic and on occasion actually arranged to help women get out of their homes to stay with people in our personal network. Any domestic violence worker in this day and age will faint hearing that. All the “safety rules” would forbid anything like that ever happening now—one woman helping another unencumbered by agency policy.

My role on the Task Force was collecting raw data from hospitals and law enforcement. There were no computers back then. Records were kept in huge eleven-by-seventeen-inch ledgers like something from the 1800s. Hospital ER logs described injuries and I found a pattern of “doorknob bruises” (black eyes the women claimed were from falling against a doorknob), kitchen counter bruises (bruised ribs), falling down stairs bruises (sometimes internal injuries), and various red marks or bloodied noses with no explanation. The mental health admissions were even more vague. None were ever listed as domestic violence. The term was not used. It had not come into common legal usage yet.

In speaking with the municipal police departments and sheriff’s offices, I learned they had a designation called “domestic disturbance” which was more specific for our data gathering. In one municipality of Thurston County the police chief told me, “There is no need to look over our ledger because that’s not a problem in this town.” Most of the police and sheriffs reported the same approach to these calls. They described taking the perpetrator out of the home to “walk him around the block” or “sit and cool off in the squad car” with admonitions to “stop doing that”—whatever that was—and send them back into the house warning they better not hear about his happening again. No one went to jail in those years unless there was extreme assaultive behavior requiring hospitalization. Some of us on the Task Force actually thought we should become policewomen to work on this from within law enforcement.

When our report was completed, we were well established as a program of the YWCA. Eventually we merged with the local Rape Relief program, also under the YW umbrella. Local women politicians and community leaders opted to get in on this growing part of the women’s movement. The Task Force was disbanded when the shelter project became “legit.” A new name was attached: “SafePlace.”

As funding rolled in for the shelter and an actual facility was established, women committed to feminism and anti-oppression kept SafePlace operating as a collective, non-hierarchical, anti-oppression organization for over twenty-five years. When the shelter movement began morphing into a program beholden to governmental agencies and grant funders, the element of the work being social justice activism shifted to standard social service agency policies and procedures. Eventually, the board for SafePlace hired an executive director and the collective model was disbanded. The end of an era.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer