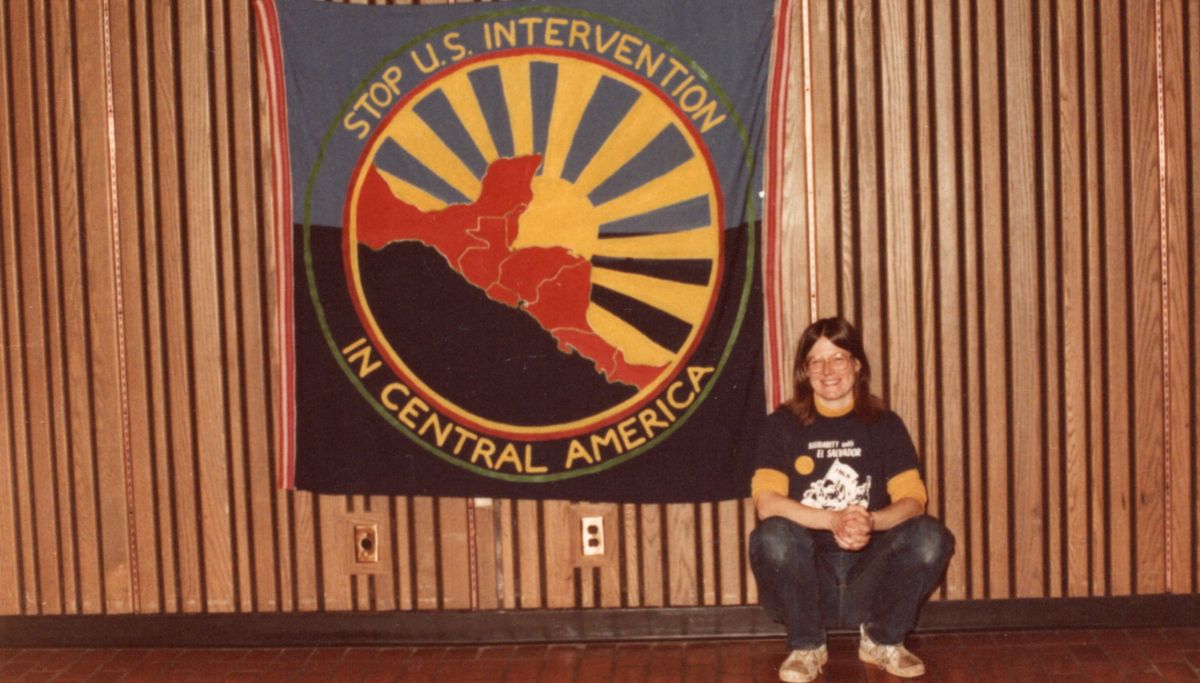

ACTIVISM

Construction Brigades in Nicaragua During Reagan’s War

By Jean Eberhardt

I resisted going to Central America in the 1980s because I believed that we all needed to stay right here in the US, in the belly of the beast, to fight imperialism. Mira Brown, a 1984 Evergreen graduate, heard me out and said I should still go to Nicaragua and see what was going on with my own eyes. She indicated it would deepen my understanding of our country’s extensive aggressions against the global south. Specifically, I would learn more about the cross-class struggle to overthrow the forty-three-year Somoza family dictatorship and the Sandinista government’s efforts to eradicate poverty and illiteracy. She had traveled there, as the heinous counter-revolutionary war of Reagan and Bush was well underway, to look into alternative energy generation.

Most of Nicaragua’s energy came from burning imported fossil fuel, and the new government wanted to develop sustainable options. I asked Mira what I could possibly offer that would be of use during the war. She mentioned coffee and cotton picking brigades, which I scoffed at as I imagined dragging myself through the fields. I had been a slow apple picker on tall three-legged ladders in Hood River Valley a few years earlier, not holding a candle to the speed of the Mexican pickers from Guerrero. Then she mentioned she’d heard of a construction brigade from San Francisco working alongside Nicaraguans to build housing for refugees, or a health clinic, or something useful while our government was funding the killing of civilians and the destruction of infrastructure. The idea of building something piqued my interest, as I had become a carpenter in Olympia six years earlier, and I could see myself traveling in that context.

During the counter-revolutionary war—a right-wing terror campaign waged by ex-national guard mercenaries, called the contra, of Nicaragua’s ousted dictator and funded by the U.S.—over a hundred thousand people from the U.S. visited Nicaragua. Many of us traveled and volunteered with purpose. For example, delegations of elected officials mobilized by progressive organizations, ecumenical study tour groups, long-term volunteers with Witness for Peace, caravans carrying material aid with Pastors for Peace, medical teams, coffee and cotton harvest brigades, and journalists. Construction brigades were self-organized to build in Nicaragua while our government financed undeclared wars of “low-intensity conflict” across Central America. These wars were low on US military deaths, but “high-intensity” with incalculable death and terror on everyone else.

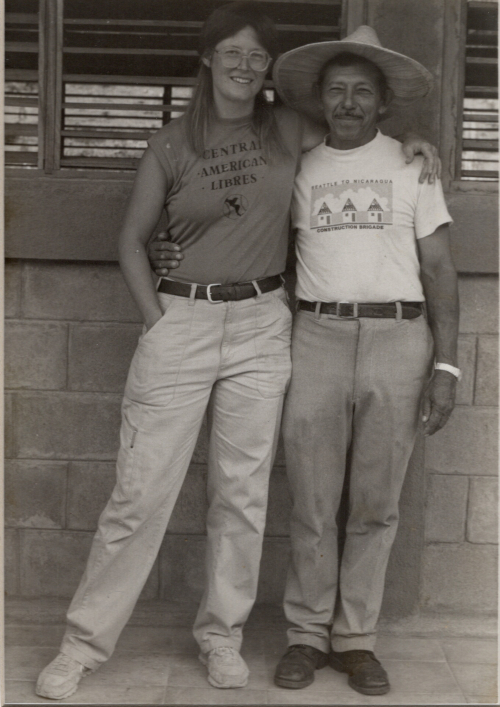

Mira found a flier posted on a telephone pole in Seattle in the spring of 1985 advertising the first construction brigade being organized from that city and handed it to me back in Olympia. My fate was sealed when I joined that group of tradespeople, spending many weekends with them in Seattle as we took on fundraising activities and events together. I was in Nicaragua by December of 1985. That three month experience profoundly changed my life.

Padre Ignacio González, a Colombian priest and liberation theologist living and working in Nicaragua at the time, found a way to complete construction on a rural school building that had been abandoned as the war escalated and defense of the country took priority for resources. Our group, via El Centro de La Raza in Seattle, learned of Padre Ignacio through the Fundación Augusto César Sandino in Managua. We committed to the project of working on that school. Because of the US trade embargo against Nicaragua and resultant shortages of goods, our group hauled building materials and tools across the border to Vancouver, Canada and shared the expense with Farmers For Peace of a shipping container to the Port of Corinto in Nicaragua.

We were called brigadistas, continuing the legacy of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade from the US that went to fight fascism in Spain’s civil war in the late 1930s. I traveled with Doug Baker from Seattle one month before the arrival of the rest of our brigade, to arrange transport out to the school building site with the contents of our shipping container, which included school desks and baseball equipment. Sixteen tradespeople from the Pacific Northwest lived and worked with dairy farming families in a rural community called Tierra Blanca near the town of Santo Tomás, Chontales. The priest, Padre Ignacio, would drop by in his pickup truck to visit and take small groups of us out to the camps of desplazados (displaced people), the people who had lost everything, including their families, to contra violence. For the first time in my life I saw naked children with parasite-filled, distended bellies living with their mothers, or other surviving relatives, under shelters made of black plastic sheets with nearby open fire cooking pits. The priest was determined that we should return to the U.S. even more deeply committed to ending our government’s brutal foreign policies and its horrific impacts on humanity.

Back on site, we worked hard alongside community members for six weeks to enclose the framework of a two-room school, laying floor tile and installing galvanized roofing, building doors and wooden louvered window coverings, piping potable water from a spring, and building latrines. We inaugurated the finished building to much fanfare and a huge barbecue, dancing well into our last night under new lights powered by the generator we’d brought. I promised my host family I’d return someday, which they didn’t believe and told me as much.

Our group of sixteen then headed off to the airport to resume our efforts in the US to stop future funding of the contra. Congress continued to approve “humanitarian assistance” but with restrictions on funding the contra, which angered the Reagan administration. In 1987, Oliver North and the National Security Council were exposed as having done an end run around Congress to get money from Saudi Arabia and Iran for the overthrow of the Nicaraguan government. It was known as the Iran-Contra Affair. Lies and deceit went unpunished while 43,000 Nicaraguans (their population was four million in 1988) were killed because of our government’s obsession with a so-called communist invasion that in truth was a widely-supported political and economic reform movement critically needed in Central America.

One month after we left, the contra entered the rural valley and attacked my host family. Don Gregorio Ruíz Borge was stabbed repeatedly in the throat until they believed he was dead. Luckily, they missed cutting his aorta and he miraculously survived, spent weeks in a hospital, and eventually moved his family to town, abandoning their dairy farm and home.

A bit of history about our brigade and the families we came to know is documented in the film “Vamos a Hacer un País” by Moving Images (https://vimeo.com/103289705).

I found out about the attempt on Gregorio’s life weeks later from a letter sent by Padre Ignacio. I was desperate to return and do something, anything, to make it better, which was an impossible proposition. I fell into depression, alternating with seething anger.

By the next year, a group of local folks and I created the Olympia Construction Brigade, with the intention of following Padre Ignacio’s lead on another project of necessity. We were stunned by the news on April 28, 1987 of the assassination of Ben Linder, a mechanical engineer from the Pacific Northwest, along with colleagues Sergio Hernández and Pablo Rosales. The ambush happened outside of the tiny northern town of San José de Bocay as Ben and his Nicaraguan colleagues measured a stream for a small off-the-grid hydroelectric dam that would power the community. Mira Brown had come back to Olympia with Ben just a few months before to raise funds for the micro-hydro project. Ben stayed in my home. On that same visit, he told his parents in Portland that if he was killed in Nicaragua, they were to understand it was our government that was culpable. We were all to understand that his life was not worth more than Nicaraguan lives, who were being killed by US bullets and landmines. Mira was determined to keep working in the war zone of northern Nicaragua which she did for several more years. Our group decided to move forward with preparations to go to south-central Nicaragua.

With the tremendous support of many people from Thurston County and beyond, we launched a 14-person construction brigade from Olympia to Santo Tomás. We raised over $30,000 through many creative fundraisers in our community and carried it in cash to Nicaragua. These funds financed most of the materials for a two-story building to house a humble, powerful group of women who formed a sewing cooperative and sewing school. Supporting these women and their new workshop was the project Padre Ignacio chose for us to undertake.

During the 1987 Lakefair Parade, we marched with banners and wheelbarrows full of tools, handing out “Friends of Nicaragua” balloons along the parade route to make clear that we stood with Nicaragua and not with the US position. This parade was the largest single event in Olympia until the Procession of the Species was launched in 1995. Though there were mixed reactions from spectators along Capitol Way, we received a standing ovation from a large sister city delegation from Japan in the bleachers set up on the State Capitol grounds. We understood this to mean they knew that what we were doing was on the right side of history, given their own experiences with the U.S. nuclear bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and US Executive Order 9066—the incarceration of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Georgina Warmoth, originally from Torreón, Coahuila, México, and I traveled to Nicaragua in January 1988 to prepare for the arrival of the rest of the Olympia construction brigade in February. It was three months after a major contra attack on the town. On the day we landed in Santo Tomás, Georgina and I met the women of the sewing cooperative in a very small room next to the Comedor Infantil (the children’s free lunch program). The space was packed with treadle machines. The women’s feet rocked back and forth, their hands pushed fabric as needles pumped up and down. After introductions, the conversation quickly went to the war and first-hand accounts of their terror. Each costurera (seamstress) recounted where she was when the attack began on October 15, 1987. They scrambled to get their children to safety. They told of brave townspeople, young and old, who fought back against three hundred contra, street by street, until they were free of the invasion. The costureras named the men who died defending the town. One died right in front of the building site where we would be working. Soon enough, we were all crying together in the helpless horror of it all.

I was reunited with my host family later that night at the Ruiz home. It was windy and the mangos rained down on the sheet metal roof over our heads, sounding like small bombs and startling me and Georgina, she didn’t sleep. She became deeply distressed about being in a war zone and putting her children at risk of losing their mother. Over time, it dawned on me that the two parents in the construction brigade felt the danger in a different way than did the rest of us brigadistas who were childless. It was Georgina’s first and last night in Santo Tomás. She returned to Managua the next day and joined Seattle’s third construction brigade on a project more removed from the war zone.

Upon the group’s arrival a few weeks later, Jeff, Bob, Shoshana, Peter, Kari, Steve, Ted, Carolyn, Donn and I met with the Sandinista political secretary of Santo Tomás. He laid out possible risks to us. He could not guarantee our safety, but promised to notify us if the contra came close to town again, in hopes of helping us evacuate should we decide to leave. We were told to stay away from the edge of town at night and certainly never to break curfew and travel on the highway after dark. There had been many ambushes on the highway and we’d seen burned out vehicles off the sides of the road coming into town. “Understood.” We scattered across town to live with the costureras and their families. I stayed with my host family who had moved to Santo Tomás for its relative safety. Don Gregorio’s visible scars and persistent clearing of his throat reminded me how close he had come to dying two years before. We shared meals of thick handmade tortillas de maiz, (corn tortillas) and homemade cuajada (cheese), eaten with boiled frijoles (beans), boiled green bananas, yuca (cassava), or quequisque (taro).

The U.S.-imposed trade embargo, as well as Nicaragua’s hyperinflation and their priority for defending the country against military aggression, manifested in shortages of cooking oil, soap, car parts, medical exam gloves, syringes, toilet paper, school pencils, and many other things. Some tomasinos and tomasinas (residents of Santo Tomás) complained of having to eat boiled beans and rice, without the benefit of enjoying them fried. Beans, rice, corn, cooking oil, sugar, and coffee were rationed and there was never enough to last until the next month’s ration. The refrain in stores, when searching for goods to buy, was “no hay” (there isn’t any). Over and over. I remember seeing used latex gloves washed and hung to dry on laundry lines outside the mini-hospital. There just weren’t any more and they had to reuse the gloves for other surgeries .

All men between the ages of 15 and 40 in the town were organized by the local committees for community defense of the Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN, the Sandinista National Liberation Front). They took shifts pick-axing through three feet of rock, creating an extensive system of defense trenches on the periphery of Santo Tomás. Vigilancia (armed night duty), listened and looked for contra movement. This was done by the same volunteers, ready to jump into those trenches with Russian-made AK-47s and to wake the town in the event of another attack. The local masons we worked with would often come to the sewing co-op building site without having slept the night before. We found an exhausted people, a country full of post-traumatic stress survivors, sapped of energy that could have/should have been going into producing a viable economy. We became acutely aware of the US government’s role in the deaths of so many people, and the destruction of countless schools, clinics, bridges, passenger buses, grain silos, houses, etc.

The sewing school and the sewing cooperative provided women with the opportunity to learn a trade and support their families. Rosaura Robleto, one of the hard-working costureras, lived with her three children in a bamboo-walled home. She was proud of her own piece of land. Parcels were given to landless people by the FSLN mayor of Santo Tomás. She looked forward to making improvements on her house as her finances improved. Rosaura had a clay-domed, wood-fired oven that she used every weekend to produce traditional corn-based Nicaraguan baked goods: rosquillas, empanadas, and viejitas. She also attended high school as an adult student, along with many others struggling to get out of poverty. Years later, she would leave for Costa Rica to find steady work.

Kari Bown remembers becoming accustomed to hearing machine gun and mortar fire at unpredictable times of day and night. When George, Jody, and Sheryl arrived several weeks later as the final members of our brigade, Kari remembers them ducking for cover when hearing gunfire somewhere within audible range of our job site. The rest of us kept working. We knew from our Nicaraguan co-workers that we were okay and the danger was not close by because they didn’t miss a beat of what they were doing at the moment. Together we dug the building’s foundation trenches, laid piedra cantera (hewn blocks of rock), cut and tied steel rebar, formed the columns, and mixed concrete on the ground to haul by buckets to the right place. Day in and day out, we worked with several of the costureras and albañiles (masons) to complete the foundation and enclose the first-floor walls. There were no such things as concrete delivery trucks there in 1988, at least not where we were. On days when we ran out of materials, we shifted our labor to the farm project, which produced food for the Comedor Infantil and still does.

One night some contra came into town and used plastic explosives to blow up a light post attached to a home, cutting off power to the town for two days, and making everyone’s nights much more tense. No one died from the blast, but someone in that home had been specifically targeted. I was six blocks away and it was the loudest explosion I’ve ever heard. Our group had an emergency meeting the next day to decide if we would stay or leave. It was obvious the contra were too close for anyone’s comfort. I stewed over the choice we’d made to walk into a war zone and wondered if we would leave unscathed. If we were able to get out of this intact, what did it mean that our friends in Santo Tomás did not have that option? We chose to remain.

During our brigade’s six-week stay, we were able to get the walls of the 2,000-square-foot building up to chest height. Because of the war and material shortages, it would take the albañiles another year and a half to complete the building. Daniel Ortega, the president of Nicaragua, joined the costureras for the inauguration of the Casa de Costura Etelvina Vigil, named after a local woman who was killed in the fight against the National Guard of the Somoza family dictatorship in the 1970s.

The Thurston-Santo Tomás Sister County Association (our outdated website: oly-wa.us/tstsca) was formed in 1989 as part of the decentralized national movement to put faces on the US wars in Central America to help make the impact real for people here, and to push for foreign policy change. Since then, 12 Nicaraguan delegations have come north to visit and volunteer in Olympia and many Evergreen students and Olympia community delegations have traveled south to visit and volunteer in our sister town. Every group that has been to Santo Tomás visited the Casa de Costura and many of us have bought handmade clothing there. Hundreds of women from town and surrounding rural communities have graduated from the year-long sewing program. The sewing cooperative eventually folded due to competition with used clothing cast-offs from the US that flooded the markets after the FSLN lost the elections to a coalition party in 1990. The coalition party was orchestrated and financed by the US and when they came to power the trade embargo was lifted. The sewing school still occupies the top floor, while the first floor is now being used as a free rehabilitation and treatment center for persons with disabilities.

Within this long-term sister community organization, we’ve supported over 50 young people from Santo Tomás to earn degrees in higher education and become professionals in their community. A few have since left the country, a few have not been able to find work in their field, but most have persisted and changed their destiny and that of their community for the better. We also fund three nominal salaries for the coordinator of the children’s lunch program and a modest public library, keeping the doors open to kids who need food and access to books. Since 1989, the TSTSCA has raised and sent financial support for numerous community building repairs, innovative farm projects, books for the library, and medical equipment for the clinic. We’ve supported dozens of delgations to come to visit both communities. For 25 years, Lincoln Elementary School in Olympia has sistered with the Rubén Darío School in Santo Tomás.

I have left unsaid how I see things unfolding in Nicaragua at this time and, for that matter, in my own country. This written reflection is about a time and place in my past that continues to inform my present.

Through my relationship and solidarity with Nicaragua, I learned to more deeply see the connections across struggles for self-determination of other countries impacted by U.S. imperialism over the centuries, as well as from the imperialist domination by other world powers. I grew to understand how my country’s bloody expansionist history and domestic policies are intertwined within an international framework of colonization and subjugation: land theft and genocide of Native Americans, the enslavement of Africans that built the wealth of this country and the extreme resistance to reparations for Black Americans, the villianization of immigrants from the global South, and the exploitation of farmworkers. I think back to telling Mira Brown in 1985 that, “we all need to stay right here in the U.S., in the belly of the beast, to fight imperialism.” There is truth in that statement, yet I believe I finally woke up in Nicaragua with the courageous people I met there, to connect global and local struggles for sovereignty and justice. I have shifted my focus to supporting the rights of immigrants here in the U.S. and the right of Palestinians to live and have self-determination in their homeland.

Update: After 35 years and much deliberation, those of us still active with TSTSCA have decided to move towards a thoughtful and well-planned end to our official sister relationship and our 501(c)3 non-profit status. We’ve given three years of notice to our sister organization to fund the remaining university scholarship students thorugh graduation, and salary support for the comedor infantil until 2027.

Thank you Olympia, and beyond, for supporting our profound relationship with a community in Nicaragua over these many years.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer