WORK

Hard Rain Printing Collective – Part 2: 1978-1985

By Don Orr Martin

We had been in the Division Street shop for a couple of years. Struggling, cold, and damp. Honing our skills. Learning from mistakes. We learned about printing standards and the allowable percentage of flawed prints or undercounts. We paid dues to the Graphic Arts International Union, in support of workers in the trade. It meant we could print a “union bug” on our work. Union affiliation was important in the political arena of the state capital (we did jobs for Dan Evans, Mike Lowry, initiative campaigns, and various local politicians). As employees we negotiated with ourselves as our bosses for a union contract. We never got much of a wage, but we were in total control of the working conditions, such as hours, health benefits, vacation time, sick leave, and the airing of grievances, which we did a lot.

I can’t remember now exactly why we had to move again, but I think Rick O’Reilly, our landlord, needed a parking lot for the restaurant and wanted to tear down our little hut. We decided we needed a business plan. There were endless meetings and arguments. We felt we should be downtown. We learned of a vacant space above a travel agency on the corner of State and Washington next door to Olympic Outfitters. The six rooms would be spacious and would put us in that core area of alternative downtown businesses. We were confident we could afford the lease and it seemed like an ideal location from the standpoint of walk-in traffic.

Except it was up a flight and a half of stairs. With no service elevator.

If we thought it was tough hauling heavy printing equipment up the driveway at Alexander Berkman Collective, this was way steeper and a truly daunting task. Mic Harper built a ramp up half of the seven-foot-wide staircase. Nancy Laich wanted to hook up a pulley system with ropes tied to a car down on the street (it might have worked, there was a straight shot down to the sidewalk and out to Washington Street but it would have meant blocking traffic for several minutes for each big piece of equipment). In the end we just heaved everything up the ramp on dollies with come-alongs and plenty of safety lines. Again, like before, women took charge of the move and did it safely.

Still, it was stressful for a number of reasons, not the least of which was our simultaneous and controversial political work with prisoners at the maximum-security penitentiary in Walla Walla who were helping Theatre of the Unemployed write a play about prison conditions. Several of the Hard Rain gang were driving across the state and going into the prison to meet with a group of inmates on a regular basis, then driving back and packing up parts of the printshop a carload at a time. I remember it was a few days after the Fourth of July, 1978. A group of young men drove past the printshop on Division and threw a string of firecrackers at us as we were loading equipment into a U-Haul. We were jumpy from our experiences with prison guards and Walla Walla police. The exploding firecrackers scared the shit out of us. Jean Eberhardt, who was helping with the move, got furious. She ran after their truck toward the light at Harrison, and with her big old, steel-toed construction boots put a good-sized dent in their tailgate. They were mad as hell, but knew they could get in big trouble, so they took off.

Downtown Olympia 1978 to 1984

Having a new downtown space excited us. The top of the stairs opened up to a large reception area. We installed a long counter with a glass top under which we displayed samples of our printing. We also did folding, collating, and stapling in the main room, and had our stereo system and reference books there. Loud music made the work easier. We often sang along to women’s music, like Holly Near, Meg Christian, Sweet Honey and the Rock, and of course Broadway musicals.

One windowless room housed the only working offset press, our platemaking equipment, and eventually our Compugraphic typesetter. Another room was dedicated to the light tables for doing layout, hanging files for regular customers’ jobs, paper storage, and the big paper cutter. The corner room with window ventilation on two sides was our silkscreening area. It had a large work table and clothes-pin wires strung the length of room used for drying the prints. We also had an employee lounge with a couch, coffeemaker, and refrigerator, and at the top of the stairs a large bathroom and a utility closet that we converted a semi-darkroom with a stand-up sink for cleaning silkscreen frames.

Nancy Laich started operating the offset press along with Grace and Greg, usually during a night shift. She had previously worked at Warren’s Quick Print, one of the bigger printshops in town, but like many women in male-dominated trades, was not treated well (she and Greg both did stints with the state printer). Nancy’s main interest, however, was alternative agriculture. She owned a farm called Common Ground and raised goats and sheep. Nancy is one of the most resourceful people I know. Down-to-earth and direct. I don’t think we paid her much, if anything, but she had full access to the facility which she used in off-hours for various personal and political projects. She and Steven Kant, for example, produced a regular newsletter mailed to prisoners in Washington along with free books for them to read. The newsletter contained information they might not otherwise have had access to.

******

I always considered myself a hack designer. I made art from an early age, but I got no formal art training. I understood various techniques and did okay, but I never mastered them. My images were often stark and flat, photographic in that 1970s high-contrast style. I was influenced by the political art of labor movements in the Americas, the pen and ink of Art Nouveau, and the geometry of Art Deco. Later, I admired R. Crumb, Andy Warhol, and Keith Haring. My goal wasn’t to create bourgeois beauty, but rather to capture regular folks and a world of contrasts and contradictions. I wanted to see more people of color in popular media. (Here is a link on this website to a gallery of silkscreened posters that includes many of my designs).

The collective considered ourselves “ad-busters,” a term that came along later and essentially meant counter-advertising or political take-offs on corporate marketing. We had a sense of humor. It was great fun doing spoofs of popular culture, political figures, and corrupt corporations. Hard Rain’s bumperstickers and broadsides were renowned:

- For “Live Without Trident,” a protest organization against the nuclear submarine base at Bangor, we did both fliers and stickers. The group used a cartoon character by Ray Collins called Dipstick Duck as its logo. Ray’s work was popular in Seattle newspapers.

- When Barney Clark became the first successful artificial heart transplant we did a bumpersticker that simply said “I ❤️ Barney Clark.” The heart had a cord and plug attached.

- When Nelson Rockefeller died (Rockefeller was the non-elected vice president under appointed president Gerald Ford following Watergate), we did a flier with a picture of his wife that said, “Rocky’s dead and I’m Happy” (his wife’s name was Happy Rockefeller). It listed wealthy Mr. Rockefeller’s corrupt policies. We plastered it around town.

- Red ink fades notoriously fast in sunlight, but our STOP VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN bumperstickers lasted for decades thanks to vinyl ink pigments.

- Perhaps most famous was our bumpersticker with the tag line of Lily Tomlin’s phone-operator persona Ernestine, “We don’t care. We don’t have to” followed by the monopoly phone company logo. Our friends would sneak around town and attach the bumperstickers to company vehicles and construction equipment. It was a scream and really pissed off Pa Bell. At one point, corporate representatives from Bell Telephone (AT&T) came to the printshop to intimidate us, but they didn’t sue or anything. After Lily Tomlin performed in Olympia during the women’s marathon Olympic trials in 1983, we met her backstage and got her to sign one of our bumperstickers (I think Marge Brown arranged that). I still have the autographed sticker.

Our political antics made us the target of occasional federal surveillance. Grace remembers an incident where we made a special order for some 100% cotton paper for a customer’s fancy wedding invitations (we did a lot of wedding invitations). At the time, US money was minted on paper with high cotton content. A couple of Treasury men showed up one day to investigate whether we were counterfeiters.

Our regular customer base expanded to include not only social service groups and alternative businesses like Blue Heron Bakery, Radiance, and the Olympia Food Co-op, but also such mainstream entities as Olympia Symphony Orchestra and restaurants like the Gnu Deli and Piranhas. Paul Stamets, the now well-known mycologist, was just starting his business and for several years had us print Fungi Perfecti, his catalog of mushroom growing equipment and supplies. We did posters and flyers for bands like the Righteous Mothers, Citizens Band, Izquierda, Obrador, Gila, and Fruitland Famine Band. Business cards were a staple.

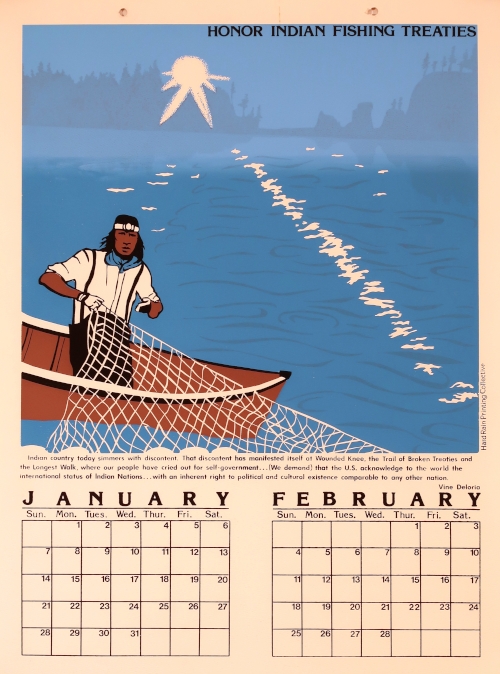

We printed a silkscreened calendar for 1979 starting later than we should have in 1978. It consisted of six original serigraphed illustrations bearing two calendar months each. January/February featured fishing rights; March/April was about violence against women; May/June millworker health; July/August revolution in Central America; September/October prison injustices; November/December lesbian rights. We worked many late days and nights to finish it before the end of the year. I don’t remember now how many multi-colored prints we pulled—maybe 300. We had no marketing plan and unfortunately sold only about half, which barely covered the cost of materials. The harsh screen-printing chemicals nearly did us in. But prints hung in many households for well beyond that calendar year. The issues those images spoke to are still in the forefront decades later.

In 1979, the lesbian community began printing a monthly magazine at Hard Rain called Matrix. A dozen or so writers, typists, and artists would take over the shop for a weekend (often with children and dogs and small potlucks). They planned the magazine around theme topics. To create each issue they used a Selectric-type typewriter, drawn or copied images, and our light tables, hand waxer and t-squares to do layout. Then it was printed, collated, and stapled on Sunday night and distributed via mail, at bookstores and cafes, or hand delivered. It became quite the social scene and creative outlet for about five years. During a time when feminist separatism was hotly debated in the women’s community, Greg and I both helped in the production of Matrix—we were dubbed “honorary lesbians.” For a short time, Jeff Cochran and I, along with other members of the gay men’s community, tried to follow this model with a men’s publication called Issues, but we couldn’t sustain it. I think we only did two or three editions. Unfortunately, no copies remain as far as I know.

The Hard Rain space became a sort of community center. It was a comfortable place to hang out downtown, to engage the leftist community, connect with social services, entertain kids, teach people about the industry, and discuss community issues. Small groups could meet there or use it as a staging area.

When we needed a break we went to the Spar. The back door was just across the alley. The Spar back then was closer to its original Deco design and was a mix of working class and small business clientele. We ate lunch there three or more times a week. The Spar also became an adjunct office—we had many work meetings in the booths up front. Waitresses Shirley and Edie had our regular orders memorized.

In about 1980 we purchased a used Compugraphic typesetter—a significant modernization for us. It was an early computerized system with several fonts. The output could be created in precise point sizes. Finally, we could move away from press-on type which was expensive and laborious. The machine used photographic paper that had to be developed in nasty chemicals, but our work now looked far more professional. The Compugraphic required flawless typing skills (typos were difficult to correct) and that work mostly fell to Grace. Young design and printing trainees like Melissa Roberts took some of the pressure off Grace, as did Mic Harper, Jeff Cochran, Cate Burnstead and Wayne Zebelman who were learning to run the press.

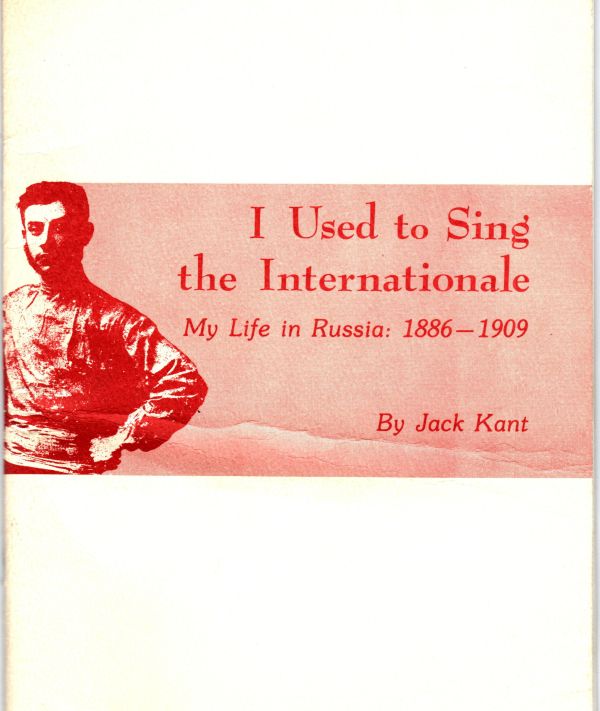

Hard Rain printed several “chapbooks”—booklets usually formatted on letter-sized paper, folded in half, and stapled in the fold. For example, a memoir of Steven Kant’s Leninist grandfather who escaped anti-Jewish pogroms in Russia in the early 1900s. Other booklets included poetry and short stories by local writers. One book we printed that helped connect us to the American Indian Movement (AIM) was produced by Nilak Butler, a well-known singer and actor at the time, who was married to Dino Butler, an Oglala Sioux member tried alongside Leonard Peltier in 1977.

Our motivation as pamphleteers was social change and we donated a lot of time to various causes. Like other small alternative businesses, we struggled to meet payroll and pay taxes. We did not have a good system for setting aside quarterly installments and in the early ’80s we were notified by the IRS that we owed $2500 in back taxes. This was as much as we paid for all the original equipment, a huge sum back then. We did not want to suffer the same fate as Gino (see Part 1) and so we begged our relatives for help. We also held a fundraiser at the Gnu Deli. Local musicians and the Karen Silkwood Choir performed. There was a female fire-eater and sword-swallower, and Grace’s dad, Bob Cox, who had been the lead actor in the Disney movie Seems There Was This Moose, read a moving antiwar monologue. We managed to pay off the debt and get back on track.

Ronald Reagan was elected president in 1980 promising to stamp out revolutionary uprisings in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala. The Vietnam War had ended only five years earlier and now local antiwar activists geared up to oppose Reagan’s imperialism in Central America. Hard Rain’s contribution was a monthly newsletter called ¡Atento! It was a community effort that forged ties with various leftist organizations around the US and Central America, some of which are still active to this day.

******

Most days I walked the short distance from Emma Goldman Collective to work. One morning as I headed down the hill, I was horrified to see a huge column of flame and black smoke rising from the corner of State and Washington. I panicked. We stored volatile chemicals in the printshop. I visualized them combusting and burning up a whole block of downtown Olympia. And us without insurance. I ran the rest of the way in terror, my heart pounding, tears streaming down my face. The closer I got as I crossed the bridge, the more I was convinced it was our building. What a relief to finally discover it wasn’t Hard Rain but a furniture store kitty-corner to us on the site of what would eventually become the Olympia transit terminal. Fortunately, firefighters contained the damage, but the fire’s intensity melted cars parked on the street nearby. We took additional safety precautions with solvents after that.

******

As a student at Evergreen, I had done an oral history project on local members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). I interviewed the last remaining survivors of the Everett and Centralia Massacres (1916 and 1919 respectively). I decided to join the radical union around the time Hard Rain started. There were several active Wobblies in western Washington in the ’70s and ’80s. We were friends with people in the Tacoma branch, including Ottilie Markholt, Allan Poobus, and Barbara Hansen. What I recall is that Allan and Barbara attended a national IWW convention in Chicago and learned that the union wanted to print an updated version of the Little Red Songbook, originally made popular by Joe Hill and soapbox speakers in the early 1900s. Thanks to Barbara’s advocacy, Hard Rain got the go-ahead and we spent weeks researching songs and making recommendations. Then we typeset the lyrics, and for many songs created simple sheet music. Musical staff paper was sized for the three-inch by four-inch booklet and we used sheets of press-on musical notes, key signatures, and guitar chords. When we finished setting a song, Grace and I would play it from the sheet music, she on her accordion and I on my recorder, to make sure we got it right. It was a glorious project.

Nancy remembered working late one evening when former members of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade were speaking in town about their experiences fighting against fascists in Spain during that country’s civil war in the 1930s. They somehow stumbled across Hard Rain. The door on the street was open and they came up. Nancy talked with these elderly rebels for quite a while. They were heartened to learn of younger folks carrying on political resistance to war and imperialism as they had decades earlier.

******

By mid-1983, our aging equipment was frequently breaking down and required constant repairs that interrupted production, making it hard to meet deadlines. The quality of our printed pieces suffered. We couldn’t afford to upgrade. Staff meetings were contentious. The guys from Intercity Transit let us know one day that they weren’t satisfied and were seeking another printer for the bus schedules. We would have to make big changes to survive. But we were burning out. Tina had long since moved on to better jobs. Greg was following his passion for radio technologies but was helping regularly on repairs. Nancy was still doing night shifts, but the day-to-day operations of the shop were mainly up to Grace and me. It was a tough time for me emotionally. My mom died in 1983 and my grandmother a few months later—the matriarchs that held my family together. My intimate relationships were falling apart. Grace and I had been food-stamp poor for a long, long time.

When Apple Computer launched a new era of desktop publishing in 1984, we could see the writing on the wall. The skills of printing and design would soon be available to the push-button masses, self-operated and affordable. Small offset printing was being elbowed aside by Xerox, Hewlett-Packard, and Canon. Big, multicolor offset presses would still be needed but they were beyond our means and desires.

The summer of 1984 Hard Rain Printing Collective closed up shop.

With Big Brother Reagan certain to be in power for the bulk of the decade, the spectre of the AIDS pandemic, continuing imperialistic wars, and backsliding on civil rights, it felt like Orwell’s vision of 1984 was unfolding before us. Social change was more important now than ever. New tactics of resistance were needed.

We were very sad to close the printshop, but I think we all were ready to move on. We had helped build and educate a radical community in Olympia, trained and mentored a cadre of activists, and contributed to important social movements while raucously thumbing our noses at capitalism.

One more time (sadly not the last) we had to move all the heavy printing equipment. Taking it down those steep stairs was a bit easier than taking it up, though still plenty nerve-racking. We sold and donated a few pieces. Everything else was stored for a while in a barn on Delphi, then moved again to the basement of Emma Goldman Collective, and much of it was hauled off later as scrap metal.

I eventually got hired in the graphic design office of the Department of Transportation—anarchist printer becomes state bureaucrat. Grace joined the staff of the Olympia Food Co-op. In writing this remembrance I couldn’t help but think of the last stanza of Bob Dylan’s 1962 song:

I’m a-goin’ back out ’fore the rain starts a-fallin’

I’ll walk to the depths of the deepest black forest

Where the people are many and their hands are all empty

Where the pellets of poison are flooding their waters

Where the home in the valley meets the damp dirty prison

Where the executioner’s face is always well hidden

Where hunger is ugly, where souls are forgotten

Where black is the color, where none is the number

And I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it

And reflect it from the mountain so all souls can see it

Then I’ll stand on the ocean until I start sinkin’

But I’ll know my song well before I start singin’

And it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard

It’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall

In the summer of 2023 the original Hard Rain Printing Collective members gathered to recount stories of our time together. Grace, Tina, and I met at Greg’s house in Olympia. Nancy Laich and Melissa Roberts also attended. Nancy provided some goat meat which I braised into a delicious Indian curry. Everyone contributed to the potluck. Over that afternoon and evening, we jogged each others’ memories of the zany and difficult things we went through at Hard Rain. Some of them are recounted here. Nearly 50 years later we all remain dear friends and comrades as well as dedicated social change activists.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer