WORK

Hard Rain Printing Collective – Part 1: 1975 – 1978

By Don Orr Martin

Grace Cox thumbed through the classifieds every day for weeks—the Seattle P.I., the Seattle Times, industry magazines, even neighborhood Thrifty Nickels—when she spotted a notice for a print shop going out of business. “Offset printing equipment. Must Sell. Best offer.” She showed me the classified ad with the phone number.

“We’ve got to call,” I said. “This could be what we’re looking for.” The person on the phone explained that the equipment had been seized for nonpayment of taxes. We could view it and make an offer.

It was 1975. Grace and I were roommates with a creative bunch of student artists/activists at the Emma Goldman Collective. We named our communal household after the inspiring anarcho-feminist rabble rouser from the early 1900s. Five of us shared a four-bedroom, 1880s-era house on the corner of Foote Street and Sixth Avenue. Olympia was also home of our recently-opened experimental college,The Evergreen State College, where we were students. We were mostly working-class kids radicalized by civil rights movements and the Vietnam War. We craved theatre, song, and social change. And, to paraphrase Emma Goldman: if we couldn’t dance, we didn’t want the revolution. We rejected the nuclear family, traditional gender roles, and conservative social values. We shared household duties and practiced the Marxist ideal: from each according to their abilities, to each according to their needs.

Indeed, it was the concept of workers seizing the means of production that inspired Grace and me to investigate the idea of running a worker-owned print shop. In the days before cell phones and the internet, print media was how we communicated, how we announced our events and rallies and theatrical productions, how we debated political change. We wanted to be pamphleteers. Thomas Paine and the Wobblies were our inspiration.

Unfortunately, neither Grace nor I knew how to run offset printing equipment. Sure, we had experience in mimeograph operation and screen printing, but offset presses were a serious step up. We needed someone to advise us on the value of the equipment.

Enter Greg Falxa, our neighbor, fellow food co-op member, and silkscreen buddy. He and his roommate John Woo created a printmaking studio in the basement of their collective household, called Blanco y Negro. Greg had worked as an offset press operator in California before deciding to move north. He was skeptical of the plan Grace and I were hatching, but we managed to get him to go with us to south Seattle to look at the small print shop that had been padlocked by the IRS.

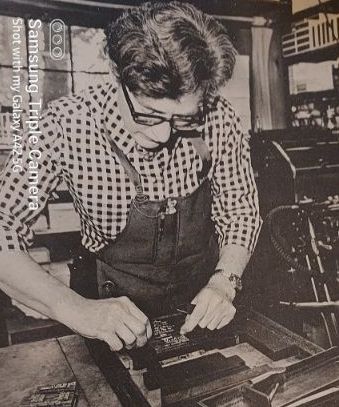

Whoever owned the shop had left in a hurry. We learned his name was Gino. Crusted ink in the press trays, the medicinal smell of blanket wash and developing chemicals, rusted plates on their drums, a thick layer of paper dust everywhere. Still, Greg saw potential. Two Multilith 1250s (probably from the 50s), two electrostatic plate makers (lots of spare parts), a classic letterpress (with a flywheel, motor, and strap), a thirty-inch guillotine paper cutter, folding machines, racks, and cabinets. It would take a lot of work to get these machines running, but we decided to make an offer. We drove over to the owner’s double-wide in a nearby trailer park.

The most striking thing about Gino was that he had no nose. Literally. Just a healed-up hole where his nose used to be which he covered with what resembled the nose cut out of a Halloween mask. He was a big, pasty guy with a full head of wavy black hair. He and his wife sat chain-smoking on a sagging couch watching professional wrestling on TV.

We asked him what happened . . . not about his nose but about the print shop being seized by the feds. He was vague on details but told us, “The guy who ran the shop printed racing forms for the horse track.” He raised his bushy eyebrows. “When the guy delivered printing orders to the track and got paid, he would use the money to place bets on the horses. Bankruptcy.”

We never found out if it was Gino who bet on the horses, how he lost his nose, or why he was so anxious to sell. We gave him a good-faith deposit ($200), the remainder to be paid upon taking possession of the equipment—$2,500 cash for everything.

Next step, how would we raise the rest of the money and where would we put all this stuff?

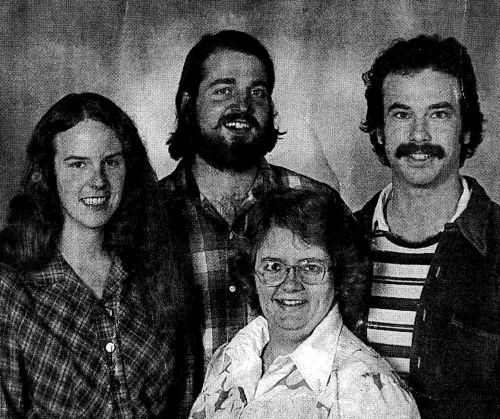

When we got back to Olympia, we immediately started fund raising. Grace, Greg, and I tapped our meager personal resources and family members. We enlisted another neighborhood colleague, Tina Peterson, to join us and help us meet our fundraising goal. Since the equipment would require a lot of refurbishing, we needed to find a place where we could work on it before there was any possibility of opening a storefront or using it to generate income. Someone suggested moving everything to the old carriage house garage at the top of the driveway at Alexander Berkman Collective (ABC) on Sherman Street. We really had no other options and so petitioned the roommates at ABC to let us use the space until we could find a suitable commercial shop. In exchange, we offered to wire the building and put in some minimal plumbing. Greg had been an apprentice electrician, and I, an apprentice construction worker.

It is remarkable to me that such a motivated and skillful group of strangers came together in a small town during an era of social upheaval. Grace was a working-class hero, deeply committed to feminism and radical politics, with musical talent and a wicked sense of humor. Greg had a scientific mind and a McIver-like character, able to fix anything using just a paperclip and chewing gum. He was also a radio technician and an avid naturalist. Tina was a brilliant student of history, and a union advocate with many skills including bookkeeping. I was a gay rights activist, graphic designer, and strident polemicist.

And then there was the person who started the ABC household. He shall remain nameless. I won’t mince words. He was a loud, abusive, obnoxious bully. He also claimed to be a leftist. He had founded ABC with Tina, but she moved out after he physically assaulted her. Despite his violent nature, this man somehow managed to charm people. He had a vision of buying the multi-bedroom ABC house and starting a land trust. Greg and I, however, did not get along with him at all. I know Greg very much wanted to be part of our printing collective, but the thought of having to deal with this guy was more than he could bear. Greg pulled out. This was a big blow to Grace and me, but we were determined to make the printshop work and decided we could teach ourselves to be printers. So we arranged to pack up the equipment and move it to the ABC garage.

Moving printing equipment is a monumental task. The letterpress and paper cutter in particular were incredibly heavy. After clearing out the ABC garage, we gathered a crew, mostly women as I recall, and with dollies and determination, we loaded a U-Haul truck and drove from south Seattle to the house on Sherman Street. Once there, we realized that we couldn’t back the truck up to the garage because of tree limbs, so we had to wheel each piece of equipment up the steep driveway from the street. My memory of the move is hazy, but as I recall we managed to do it without any mishaps or injuries. Women are more safety conscious than men when it comes to moving heavy objects and the moving crew was mostly women. Little did we know then that we would end up loading and unloading all of this aging technology at least three more times.

Divorcing ourselves from the loud, abusive, obnoxious bully at ABC house was a big motivaitng factor in the printshop’s evolution. Grace, Tina, and I somehow convinced Greg to work with us when our nemesis wasn’t around. Admittedly we were lost without Greg’s printing expertise. The three of us promised Greg that as soon as we got the equipment running, we would move out of ABC. So, Greg set us to dismantling, cleaning, inventorying parts, buying some replacement pieces, reassembling, and testing everything. All the while he explained printing principles and processes. It was a great way to learn. I built a four-by-six-foot fiberglass sink for cleaning silk screen frames so we could continue making large posters while we learned the offset presses.

Through the fall we strategized about opening a collectively-owned print shop. We had no intention of becoming a capitalist business—mainly for philosophical reasons, but also because we had no capital, just a fleet of depreciated machines and our labor. We established ourselves as a non-profit organization with the goal of providing printing and graphic design services to community groups and political causes. We wanted to be able to cover our costs and pay ourselves enough to meet our living expenses. We all studied small business guides for the pricing of print jobs because we didn’t want to undercharge and lose money.

Greg and Grace would be the press operators, I would focus on graphic design and layout, and Tina would develop management and bookkeeping systems. We picked the name Hard Rain Printing Collective, inspired by Bob Dylan’s protest song A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall, apropos for the South Sound climate. Greg designed a promotional card with a bolt of lightning and we shopped our idea of a low-cost printing facility around town.

Our plan moved forward, stoked by youthful energy and, it must be acknowledged, the innovations offered by The Evergreen State College. Establishing a collectively-run print shop was the basis of my individual study contract at Evergreen with George Dimitroff as my faculty member and Grace as my internship contractor—she wrote my quarterly evaluations. We got one press running while Greg instructed us on platemaking and Pantone ink mixing. I continued silk screening, now using photo-emulsion instead of hand-cut stencils. Grace quickly got proficient as a press operator.

Through the winter of 1975 things remained tense with the guy at ABC house. However, about this time, I met Hugh Patrick “Rick” O’Reilly through my work at the Gay Resource Center. Rick was a wine expert and a chef. And bisexual. He had just opened his own French restaurant called La Petite Maison in an old house he remodeled on Division Street. Next to the restaurant was a rugged building that had previously been a furniture refinishing shop. It was empty and it caught my eye. When I learned Rick was the owner, I asked him if I could talk to him about renting it. He invited me over to his East Bay waterfront house, fixed me steak Diane, and we discussed a rental agreement over bottles of merlot. He tried hard to seduce me that night, but I played coy and objected that it would make for an awkward business relationship. Plus, he was married to a woman who was away for the evening. Not having sex with Rick was my first of several close encounters with AIDS. Hugh Patrick O’Reilly was one of the first casualties of the pandemic in Olympia in the early the 1980s.

With the lease secured and my honor in tact, we moved all the equipment (our second loading and unloading) to the shop next to La Petite. Grace remembers that when an employee at Rowland Lumber on the corner saw us struggling to get the heavy letterpress through the loading door on the side of the building, he offered their forklift. We painted the building, covered the front windows with plastic to stop the drafts and moisture (bad for paper storage), put in a heater, and commissioned Joe Tougas to make a sign for above the front door. Hard Rain Printing Collective officially opened in 1976.

I built a wall-mounted light table for doing page layout (with a t-square and hand waxer), and shelves for storing parent-sized paper stock (26 x 40 inches) in different colors and finishes. We also had standard-sized bond that came with the equipment and reams of this weird glossy under-sized paper that we stacked up and used as a couch.

Paper selection and ordering was a new skill to learn. We established a relationship with West Coast Paper salesman Joel Onstead, whose territory encompassed Tacoma to Centralia. He was willing to have their truck deliver small quantities of paper and ink on 30-day credit. Joel, and the company truck driver, Frank, stuck with us for the next decade and we always enjoyed their visits.

Jocelyn Dohm, our friend and neighbor, mentored us in the printing business. For decades she ran a letterpress shop, Sherwood Press, in a cozy cabin behind her family’s original west side home just down the hill from Emma Goldman and Blanco y Negro. Jocelyn’s shop had a top-of-the-line Heidelburg press that she kept in immaculate condition, banks of cold type, and, in my memory, an elfin fireplace. She was a lesbian peace activist from the 1950s, and a business outsider like us.

We didn’t have a copy camera, so we had all our negatives, stats, halftones, and enlargements made at Line N Tone downtown—Bob Wibbels and his son Bobby were also loyal business associates. I learned a lot from those two.

For the first few months in the Division Street shop we ran on donated labor. We each were employed in other jobs. Grace worked as a secretary at the legislature. I had work-study jobs at Evergreen. Greg was employed by the state printer and a copy center. Tina was our first paid employee. She had been on the government VISTA program working at Off-Campus School. Sadly, she and other women at the school were being sexually harassed by one of the male teachers. To keep her VISTA funding after she left the school, she came to Hard Rain, taking a cut in pay (the difference between what we could afford and her previous VISTA stipend). Tina set up our double-entry books in a paper ledger to track our expenditures and income. We kept up this ledger until the very end.

We all strategized about potential regular printing customers, like Gino had with his racing forms. We decided to sell the old funky letterpress because we didn’t have trays of lead type or a business purpose for its use. A poet in Port Angeles bought it and used it to self-publish his work, successfully I heard. The sale gave us enough money to buy various supplies and a little time. We had a few walk-in customers. Tim Girvin, who was the graphic designer at Evergreen back then, recommended us to a few people, including Mansion Glass—he had designed their logo and we printed their letterhead and business cards. Blue Heron Bakery had us print their bread labels. We got jobs from anti-nuclear groups Live Without Trident and Crabshell Alliance.

Then out of the blue one day, Dan Snow and Jim Slakey, managers from Intercity Transit, walked into the shop. Greg chatted them up and learned they were accepting bids from local printers to produce printed bus schedules, monthly passes, and interior bus advertising. They needed to cut the cost of what they were currently spending. This was a big opportunity for us. We worked hard to return a bid that wasn’t so low it made us look unprofessional but low enough to get approved. Somehow, we succeeded.

And so began a relationship that sustained our wages and a host of radical community projects for almost 10 years. I designed a new look for the bus schedules—a “strip-map” with just the route and fragments of cross streets that corresponded to the bus stops. It was bold and easy to figure out. This was in the days before computers and desktop publishing. I used line tape and press-on letters to create the originals. All the schedules were printed on 8.5-by-14-inch paper with a double parallel fold. Right away we realized we needed help doing production—from layout, to sorting, folding, and packaging. We started a practice of training many other young people to be apprentice printers, whether volunteers, on government employment programs, or sometimes fully paid employees. The IT managers must have known about us being radical activists but they were cool. Greg remembers that a couple of them would use the excuse of picking up boxes of freshly printed schedules to leave the office and hang out at Hard Rain, sometimes nursing weekend hangovers.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer