ARTS

The Olympia Phenomenon

By LLyn De Danaan

The story of music in Olympia most assuredly goes back before I moved to the area and began paying attention in 1971. Olympia has a history not just of supporting roots music but also of being a Mecca for jazz artists, a petri dish for punk and garage, and a rich soil for the growth of Latin influenced bands.

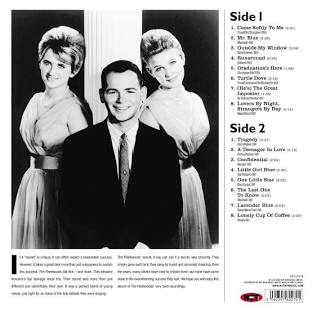

Before 1970s, there were notables like the Fleetwoods whose Come Softly To Me hit the top of the charts in the late 1950s. The Fleetwoods were the first group ever to have multiple hits in the Billboard Top 100. The unsinkable, unstoppable Gretchen Christopher, a member of the trio and writer or co-writer of many of it songs, does solo work still and released an album in 2007.

Coming to the fore, a bit after the Fleetwoods, George Barner (one year behind Gretchen Christopher in Olympia High School), known as “Big George”, was a well-known rocker with Trendsetters. He was involved in local politics in later years. Barner’s sister was the well-known Gracie Hansen who ran a Las Vegas Burlesque at Seattle Century 21 Exposition in 1962 called Paradise Club. Later she fronted a show in Portland then ran for mayor and Governor of Oregon. I saw her review in the late 1960s when she hosted at the celebrated “Gay Nineties” themed Barbary Coast Lounge in Portland’s Hoyt Hotel. By the time I met George in 1972, his voice was already as raspy as a bear’s growl from years of hollering the lyrics to Louie Louie. (It was Washington State’s favorite and, because of a 1985 campaign drive in 1985, almost became the State song.) Thousands of people came to Olympia for April 12, 1985 Louie Louie Day (declared by the State Senate) to hear the Wailers, the Kingsmen, and Paul Revere and the Raiders rock the State Capitol grounds.

Around about 1959, Don Rich (1941-1974), born Donald Eugene Ulrich in Olympia, was playing his fiddle and guitar in local venues. Known as Don Ulrich then, he was in Barner’s class at Olympia High School. Still a youngster, he was part of a band called the Blue Comets. That band, working in a south Tacoma restaurant, was observed by Buck Owens. Don was recruited. He stayed with Buck Owens until his own, tragic death in a motorcycle accident in 1974. Together they made country music history and recorded hit after hit. A recording that shows off his fiddle playing is Tumwater Breakdown, named for the town where he grew up, still considered a suburb of Olympia then. Tumwater Breakdown is on Don’s posthumous anthology album called Country Pickin’.You can listen to a clip at:

http://www.rhapsody.com/artist/don-rich/album/country-pickin-the-don-rich-anthology/track/tumwater-breakdown

For memories of Don by his Olympia High School friend:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0aXIEjdCLV4

By the 1970s, a spectacular local jazz scene was treating Olympia audiences to top of the heap music. Bassist Red Kelly (died 2004), who had toured with Woody Herman and played with Harry James, Claude Thornhill, and Stan Kenton, among others, opened the Tumwater Conservatory of Music. Before that he was playing around town at venues like the old Governor House on Capitol Way (and he famously ran for governor with the OWL Party in 1976). He was joined by, among others, Jack Perciful (died 2008), a master pianist who had played with Harry James for 18 years, and, occasionally, by the redoubtable, iconic Ernestine Anderson. Jan Stentz (died in 1998; vocals) and her husband Chuck (1926 – 2018; tenor sax) performed regularly with Barney McClure at the piano. Barney wrote arrangements for them. Chuck and Jan Stentz owned Yenny’s, an Olympia music store, during this period.

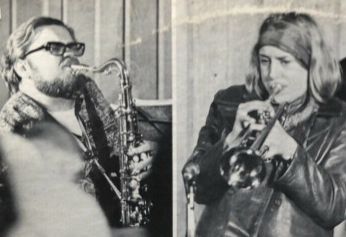

From the late 1970s through the 1980s Olympia continued to be a hot venue for jazz and often featured musicians like Bert Wilson and Barbara Donald (1942 – 2013), called, “one of the most original trumpet voices of her generation.” She followed Bert to Olympia. Her group Unity recorded one or two albums in the early 1980s. Bert Wilson followed friends from Berkeley to Olympia in 1980. Bert played with Smiley Winters and Sonny Simmons, and saxophonist Jim Pepper. Bert (1939 – 2013) performed and recorded regularly.

Joe Baque (1922 – 2022), a seasoned studio pianist who played with Lena Horne, Stan Getz, and Louis Armstrong, moved to Olympia and became a beloved fixture. He died at age 100. According to his published bio, it was love not musician pals that brought him to Olympia in 1983. Not only was Baque simply terrific as a soloist, he was generous to other musicians with his time, advice, and production savvy. He was a sought after accompanist and his name alone drew a crowd and introduced a fledgling vocalist with all the bells and whistles Joe could muster . . . and those are aplenty.

In the past few years, Jessica Williams (1948 – 2022), the brilliant jazz pianist and composer, moved to the area and appeared periodically at venues like The Art House. Jessica, who played with Stan Getz, Tony Williams, and Eddie Harris among other greats, received a Guggenheim in the field of composition and was praised by people like Dave Brubeck. She had a healthy following and a resume that read like a who’s who in jazz.

Must not forget the considerable Latin thread that has wound its way into the fabric that is Oly music. We locals celebrated Obrador appearances from 1976 through 2006. The group included Steve Bentley (drums), Steve Luceno (bass and guitar), Michael Moore (1947 – 2023; piano), and Tom Russell (primarily known for his hot woodwinds). In addition to club and festival appearances, Obrador, in its early days, played benefits for Greenpeace and the Crabshell Alliance among other progressive organizations. As an original member explains, “Obrador in Spanish means worker or workshop and obra can mean a work, construction, or musical composition. It was exactly what we were all about. A labor of love so to speak.”

There are so many other groups and individuals it is impossible to name them in this brief review. But the participatory ensembles must be mentioned because they may be, in the end, the heart of it all. The Citizens Band first played at Evergreen State College on Earth Day. Harry Levine is credited for being the first mover of the group. He moved to Olympia in 1983 with the hope of starting a radical arts collective. There are four long timers on board (according to their web site). The band is unapologetically leftist, critical, and anticapitalist. The indefatigable Grace Cox, an original collectivist with Hard Rain Printing and a long-term member of the Olympia Food Co-op staff, plays bass for the group. She wrote the lyrics to “Doin’ It,” one refrain of which includes this quintessential Olympian analysis of the world’s problems:

So I said to myself, Self what is the matter?

What’s keeping all these people from doing what they’d rather

It’s the chase for the dollar, the drive for success

That’s keeping folks content with such unhappiness.

Artesian Rumble Arkestra, whose members play for progressive fundraisers, welcome all comers and stand out on the corner of Percival Landing and 4th Avenue every Friday afternoon, rain and snow be damned. This is a group in the tradition of Honk! and street band culture. The philosophy of Honk! has been promulgated by ethnomusicologist Charlie Keil (Born to Groove) and spread by his students far and wide. Members blow their horns and beat their drums and generally play music that is of and for “the people.” Honk! enthusiasts aspire to overcome the “arbitrary social boundary” between performer and audience, a kind of “Dancing in the Streets” while blasting through the “fourth wall.”

Activist, pianist, and trombonist (her Artesian persona) Becky Liebman seems to have been critical in bringing this perspective on music and action to Olympia. She was involved in the first days of Samba OlyWa, a dynamic organization that evolved and is evolving still from its appearance at the first Procession of the Species in 1984. Essentially democratic at its core, it is open to anyone who comes out to practices either to play percussion or dance. Becky, aside from her membership in Arkestra, has been a key member of the band Bevy. Indeed Becky’s spirit and philanthropic commitment to social justice has been critical to the development of a trademark music that helps define Olympia. Nonprofessional, participatory expression of pure joy through music and movement, characterizes this brand.

Bevy’s members were either mentored by or regularly play with people already mentioned. Nancy Curtis for example, was Bert Wilson’s partner and though primarily a jazz musician, she can play just about anything and thrills audiences with her polish and virtuosity. Lisa Seifert not only plays clarinet with Bevy but hosts choro parties that draw folks from across the Oly music scene.

Not to say that The Evergreen State College didn’t in someway put its own musical stamp on the community. Arguably, its contribution to the Olympia scene came by way of providing a critical, progressive ambiance for composers and musicians, access to studios and technology (for enrolled students), and a general support for a local paradigm shift that supported and supports creativity and progressive values. Still, there were specific people and events associated with the college that surely had an influence on local music.

One early faculty member was the charismatic Dumisani Maraire (1944 – 1999) from Zimbabwe. His experience at the college perhaps exemplifies the clash between classical academic standards and perceptions of “professionalism” vs. the world music/participatory sensibility he brought to students. Specifically, a colleague of his, though ostensibly an expert on Indian tabla drumming (but not himself a drummer) continually complained about the “noise” Dumi made in his classes. Since those days, the colleague’s work has been roundly criticized in print by other professionals for its lack of accuracy and misreadings of the Indian tabla tradition. The inaccuracies are at least partly, the critic claims, because the man did not himself play. I’d like to say that such tight-assed approaches to music and performance didn’t exist at all in the early days of Evergreen. What I can assert is that it was, arguably, the college’s progressive ideology as a whole and its ability to draw innovative, broadminded students to the area and not individual faculty (with some exceptions) or programs, that contributed to the making of the Olympia Phenomenon.

Dumi performed with and taught mbira and marimba and often said, “If you can talk you can sing, if you can walk you can dance.” His students fanned out across North America and formed marimba groups wherever they landed. And his son (Tendai Maraire of Shabazz Palaces Hip Hop collective in Seattle) and other Maraire kin carry on and honor his legacy with various projects.

Evergreen also brought the fabulous Odetta (1930 – 2008) to Olympia as an artist in residence in 1982. Odetta, like so many contemporary, eminent roots musicians, did not grow up with folk music. She learned, listened, and even visited the Library of Congress’s Archive of American Folk Song to grow her repertoire. The Archive was founded in 1928 and was consolidated with the Archive of Folklife Center and renamed the Archive of Folk Culture in 1978. The Traditional Music and Spoken Word Catalog contains “approximately 34,000 ethnographic sound recordings,” made between 1933 – 1950, including all of Alan Lomax’s work. It is a abiding source of information and inspiration for serious roots musicians and students of Americana.

*****

The bicoastal Riot grrrl movement, often referred to as a feminist punk movement, was strong in Olympia beginning after 1989. Precursors locally were women’s bands such as Noh Special Effects (known for “skank, slam, and wiggle according to one of their gig posters) including performance artists such as Chelsea Bonacello, appeared occasionally in the late 1970s and early 1980s at the Rainbow and Carolyn LaFond’s coffee shop, the Intermezzo. The Intermezzo opened in 1978 and has been touted to have housed the “first espresso machine installed between Portland and Seattle.” The Intermezzo also provided a gathering place for the women’s community, including activists, writers, and musicians.

*****

Maybe it really is the water as Olympia’s eponymous beer claimed was what gave it a unique, indefinable quality. It could be. People still happily trek to the artesian spring at 4th and Jefferson to fill vast jugs for their weekly supply. According to one blogger, a 1940s survey identified 96 active artesian wells and springs in the general area of the town. Olympia beer arguably put Olympia on the map but being known as “the hippest town in the west” has kept it there and helped its resident hip-types develop a kind of self-consciousness about its unique status.

But beyond hip, it is has more happening music per capita than most other US burgs. Maybe its just something about the magnetic position of Olympia on the earth that causes everyone here to pick up an instrument and want to play it with somebody else. I really don’t know. It just seems true. One of the first things you learn about someone at a party is that they have a guitar or a fiddle or sing. Next thing you know, you are making plans to play together or listen to each other.

The zeitgeist that has characterized Olympia of the past forty years required a mixture of ingredients and cultural inventions to come evolve. We know that “synergy” is defined as the coming together of two or more things that then produce something bigger, greater, and different than the mere sum of parts. So Olympia provides a context for synergetic things to happen and for people to find each other and play together. But what are the ingredients that helped this happen?

Because I don’t know what Olympia was like in the 1950s and 1960s, I’ll talk about the early 1970s. That’s when the paradigms were shifting. It was a period of antiwar protests, it was a period of growing feminism and gay activism, and it was a period of experimentation with alternative cultures. It was all of this and much more. Coincidentally, The Evergreen State College opened its doors in Olympia and drew people to it who were engaged in all of the above. They started businesses, co-ops, and musical groups. They started producing, not just consuming. The definition of family and community was massaged into something that included chosen families, networks of friends with like values and goals and teamwork. People out of the early ’70s started organizing workshops like the popular Puget Sound Guitar Workshop (1974) where musicians and wannabes met, bonded, and came home with a will to keep playing together. People found each other, invited each other, built on each others’ expertise and ideas, and voila.

Put this together with the simple fact that Olympia’s downtown core, with its principle venues, is small. You can walk the stretch of Capitol Way between the capital grounds and the public market within about 15 minutes. Along the walk, you pass a small but accommodating Sylvester Park with a beautiful gazebo . . . the park and gazebo just perfect for rallies and small outdoor concerts and all kinds of festivities. In the market itself is a covered stage for performance. Theatre spaces in the core that were on their last legs were long ago usurped for community-based productions, particularly the Olympia Film Society’s Capitol Theatre which hosts music groups galore as well as music festivals. Combine this with the availability of relatively inexpensive housing on both the east and west sides of Olympia, commodious thirties style houses. These were quickly occupied by students looking for shared housing possibilities after Evergreen came to town. The houses were and are amenable, some of the larger ones, for the use of politically-based communal houses as well as for musical rehearsals and the development of pickup, experimental bands.

Think emergence theory. No one thing or person or event explains the Olympia music scene and its propensity to attract and support great musicians. As in philosophy, the very complex set of interacting groups and people in Olympia is what it is because of many individual events and actions over the years. It is what political philosophers might call “made order” as opposed to a conscious creation. It is real, it is palpable, and we all benefit by what we have collectively created here.

It is probably true that most of the musicians don’t have health insurance or much of anything else. They barter, tend to live simply, work day jobs so they can make music at night, give lessons to newbie’s and wannabes to supplement the little that comes in from gigs, and generally walk lightly on the planet. The professionals haven’t got much either. And they really do have to keep working many more years than those who have regular jobs with “benefits.” Jessica Williams put out a plea for help to cover a year of not playing because of spinal surgery. That’s the position people who give us years and years of pleasure end up in given our current system of health care and support for the arts. But it is also, for some, that state of relatively happy deprivation and simple, musical living that makes Olympia what it is. And you thought it was just another state capital.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer