ACTIVISM

The First Lesbian Community Meetings

By Anna Schlecht

I showed up in Olympia because I figured if gay people were anywhere, they’d be on the West Coast. But in the 1970s, they weren’t easy to find–there was no visible gay community yet, only invisible social networks. The Stonewall Rebellion may have lit the fuse of what was then called the gay liberation movement in 1969, but it took many years for that liberation to reach all parts of the country, especially Olympia.

In the early 1970s, most of Olympia’s LGBTQ+ presence seemed to be based within the relative safety of the Evergreen campus. The only non-campus group I was aware of was the Dorian Group, a gay men’s political action group that met quietly at the Rib Eye Restaurant, now known as the Martin Way Diner.

While I had the impression that Evergreen was some kind of gay oasis, I later learned life was not so easy for gay staff, students, or faculty there. The only physical presence of Gay Olympia I could track down was a Gay Resource Center founded by LGBTQ+ students during Evergreen’s first years. As a young semi-closeted lesbian, I would read the GRC minutes thumbtacked to a bulletin board outside their office. Those typed-up minutes gave me hope for the community I was searching for.

Later, I found traces of a nascent gay community while working at the brand-new Columbia Street Food Co-op. The Co-op was a community crossroads, so amidst all the amazing people who shopped there, I met lots of lesbians. It was also a great place to find households of like-minded people to live with, including women’s households. These women’s households strengthened the sense of a real gay community.

For gay people who were not Evergreen students, the Olympia community was a somewhat inhospitable place. In those days, we still referred to ourselves as gay, sometimes as gay and lesbian, but we glossed over others who identified as bisexual. I knew precious few people who identified as transgender although trans folks were always a part of our community.

By the mid-1970s, a number of activists who identified as “Various and Sundry Lesbians” began talking about ways to bring the community together. Until then, the gay community was clustered into social-networks like the activists, the sports dykes, the professionals (i.e., people who worked for the state), the bar crowd and others just living their lives. The hope was to cobble together a stronger, more cohesive community.

As an activist, I often pondered the meaning of Eleanor Roosevelt’s famous saying about universal human rights,

“Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home–so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood he lives in; the school or college he attends; the factory, farm, or office where he works. Such are the places where every man, woman, and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere.”

She could have been writing about my people, because gay rights in big cities were meaningless if we didn’t have equality in the small towns we called home.

First, the organizers got a post office box under the name of “United Feminists of Olympia” or UFO. The idea of hosting a lesbian community meeting emerged as the best way to gather people together. A date was set for a meeting and a room was booked at the old Senior Center at the corner of State and Columbia.

I was keen to learn more about this group. The woman I was dating at the time was one of the core organizers, so I asked if I could join. She told me it was for lesbians only, not people like me who identified as bisexual. I waffled a bit, partly because I wanted to keep seeing her but also because I wanted to be part of this work. I also knew that I was, in truth, a lesbian—something I’d known since the age of three. But in my mind, identifying as bisexual signified a more inclusive identity. This was decades before the full roll call of LGBTQ+ or the more concise “queer.” I doubt the woman who served as a gatekeeper was truly a separatist; more likely, she too had been pressured to adopt the groupthink to fit in. But if I wanted to be part of this group, it seemed that I had to conform. So, I did.

Sadly, I repeated this act of exclusion when a close friend told me she wanted to become part of Matrix, Olympia’s feminist-lesbian magazine. Matrix was a focal point in our community, and the weekend-long work sessions to lay out the copy functioned as a de facto lesbian community center. I told her that she needed to be a lesbian to join our collective. I’ve long since apologized to her, but these two experiences on both sides of our youthful LGBTQ-Stalinism were cautionary tales on the toxic dangers of peer pressure. Nowadays, we deride such judgmental exclusion as political correctness run amok.

Lesbian separatism was a big deal in those days. Some women thought that bisexual people were just too afraid to come all the way out, preferring instead to dip into the edges of the lesbian community before slipping back into the privileges of being straight. Others were adamantly against transexual women, as they were called in those days. These separatists believed that trans people would rather switch than fight oppression.

A very controversial 1979 book, “Transexual Empire,” derided transwomen as reinforcing traditional gender roles and sexism against cis-gendered women. One of my close pals and role models wrote a piece for Matrix debunking the transphobia in the book. That made sense to me—no one else should ever get a vote on how to embrace or present one’s own gender identity.

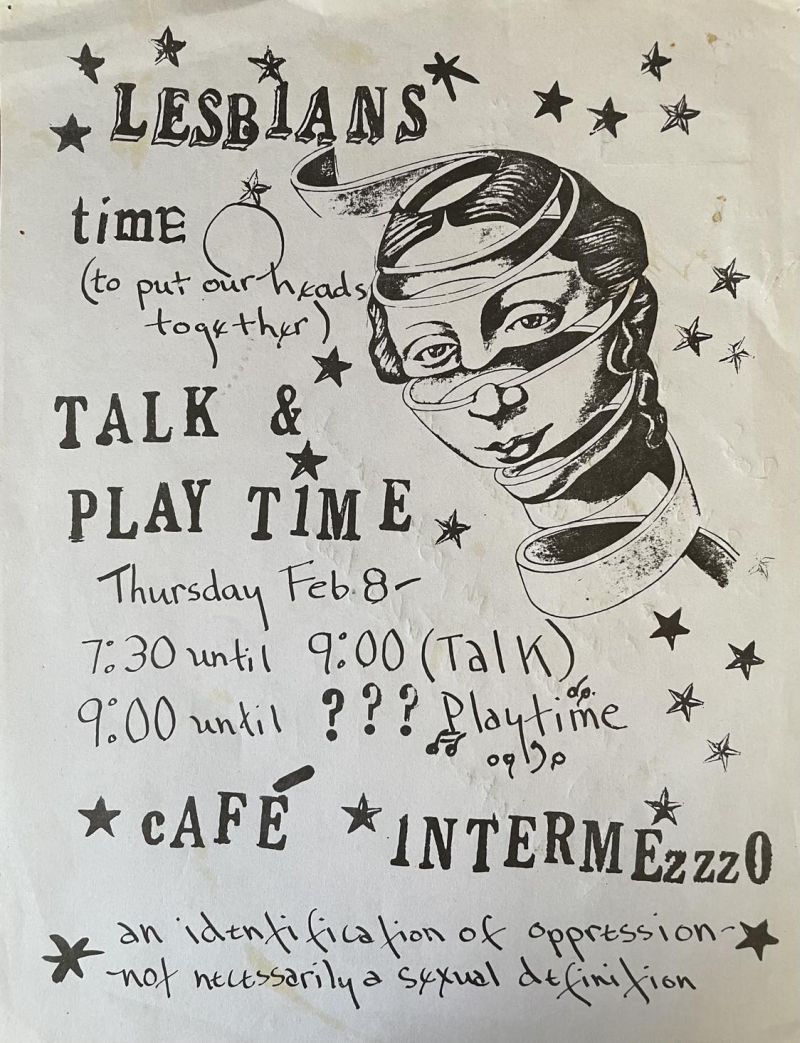

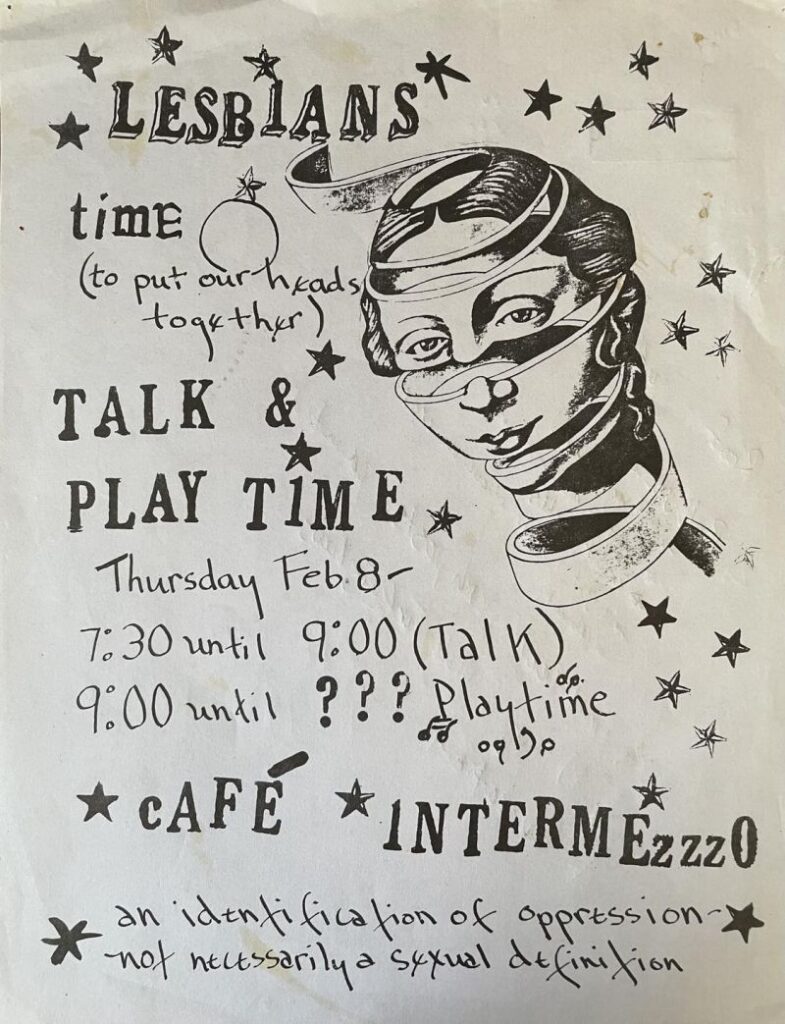

I don’t recall how the planning meetings went, but despite my own forced conformity, we landed in a place of inclusion. The event poster announced the meeting as a “Meeting of the *Lesbian Community,” with the asterisk going to a footnote that explained that any woman who was lesbian-identified was invited.

The poster ignited a firestorm of controversy. In the weeks leading up to the first meeting, torrents of argument erupted over who could attend. The question focused on who was a “real” lesbian. Debates raged over whether bisexuals or straight women deserved to be included.

On the night of the meeting, we organizers arrived early at the Senior Center to set up chairs and get ready. Instead, we were called into the director’s office. He proceeded to berate us and proclaim that he could not allow this “beast” into his Senior Center. Then he told us to get out of the building. For a moment, we stood there stunned–this was a public building owned by the City, but we were unwelcome “beasts,” not allowed to rent a meeting room. Then he again ordered us out of his building and onto the sidewalk.

We stood befuddled on Columbia Street, until other women began to arrive for the meeting. Many had come pumped up to argue about who should be invited, but once they heard what had happened, most of the divisions fell away.

Suddenly, everyone there had the shared experience of being discriminated against as queers, whether or not they publicly identified that way. Nearly fifty women found themselves standing sullenly on the dark street with nowhere to go. One of the women in the crowd, Carolyn Street LaFond, owned Café Intermezzo, a nearby coffee shop, and she invited everyone to come over there to meet.

As everyone trooped over to the coffee shop, a new mood infused the crowd–we needed each other and could not afford to exclude anyone who found common cause with us. The ensuing meeting crackled with the excitement of women ready to dive into community-building with ideas pouring out in rapid succession. Helen Thornton pitched the creation of a women’s health center, later called the Olympia Women’s Center for Health or OWCH. A couple of women who had been involved in an Evergreen-based cultural arts collective called Tides of Change offered to expand it to become more deeply embedded in the community. I pitched a lesbian community newsletter that would soon be renamed Matrix.

At one point, Grace Cox summed up the earlier controversy around who belongs by quipping, “This business of who is and isn’t a lesbian is ridiculous. I know every woman here, and I remember the last man they slept with!” Grace’s joke helped us to see that we were a community and we needed each other.

Looking back, I learned one of the most powerful lessons of my life that night–that building community; building coalitions is the way forward. At that time, musician and community organizer Bernice Regon (1942 – 2024) of Sweet Honey in the Rock had much to say about coalitions being different than hanging with your besties: “Today, whenever women gather together, it is not necessarily nurturing. It is coalition building. And if you feel the strain, you may be doing some good work.”

Much later, during the era of anti-LGBTQ ballot initiatives in the 1990s, I got a great one-liner from the late Donna Redwing (1951 – 2018). Redwing was a strong proponent of coalition-building and helped to mobilize a successful resistance to the religious right’s attempts to codify homophobia. In her public speaking, she often said, “We always do better when we draw circles to include rather than lines to divide.”

That night at Olympia’s first lesbian community meeting, a room full of woman-identified people learned how to work better together; we learned that drawing lines to divide made us more vulnerable to attack and that drawing circles to include made us stronger.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer