ACTIVISM

The Communist Party in 1970s Olympia

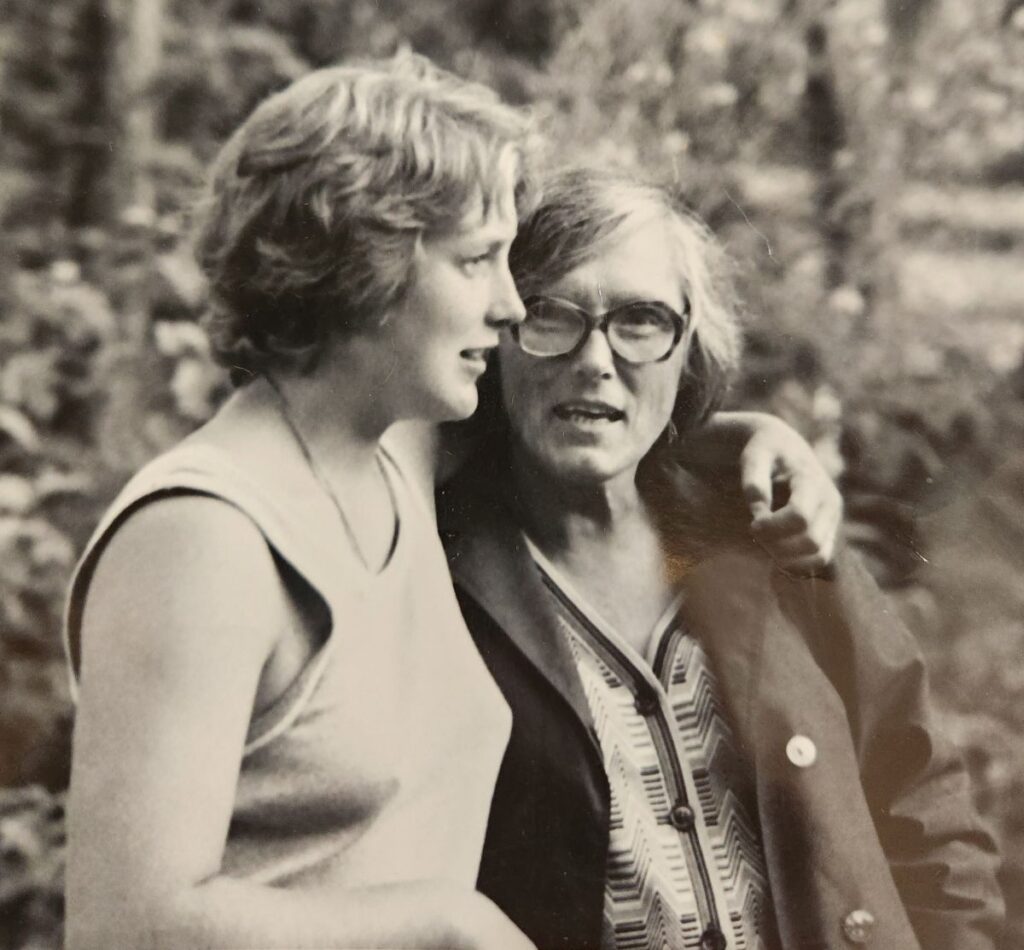

Ann Vandeman talks about her experience with

the most energetic, optimistic, warm, and hardworking people

By Bethany Weidner

Ann Vandeman was in her kitchen on Sixth Avenue in Olympia. She was making me dinner as I asked her questions about what it was like being involved in the Communist Party here in the 1970s. The actual CPUSA. I was curious and I figured my Works in Progress readers would be, too.

Ann works as a CPA now (similar initials, different intent). Before that she founded and ran Left Foot Organics, a farm program that employed and supported people with disabilities as growers. Her daughter, Geraldine Jennings, was born with Down syndrome, which motivated Ann and her husband Chris Jennings first to delve into the social and economic politics of disability in the US—and then to do something about it.

Ann grew up the daughter of a popular pediatrician dad (a prolific source of antiwar letters to the editor), and a psychiatric social-worker mom confronted daily with the dire consequences of poverty. As Ann noted, “The world view around my house was ‘poverty is bad,’ (Mom) and ‘war is unnecessary; it’s just to dominate’(Dad).”

When her parents divorced, 10-year-old Ann lived mostly with her mother, who was always ready to engage in animated conversation with Ann and her friends. “My friends loved coming there,” Ann said, “but I spent time with another family in the neighborhood. The Plajas lived on the corner of Cushing and Madison, and it was a happening place in those days.”

There were lots of kids and lots of activities—plus PB&Js. Ann went to school with two of the Plaja kids and was close friends with LeAnn. Their dad, Bob, ran a salvage business off State Avenue downtown. Ann and the other kids hung out at the store and sometimes helped out on jobs. Once Bob had a contract to clear out a nursing home and Ann scored an old leather suitcase with straps.

As we were talking, Ann interrupted to ask Geraldine to set the table, and we sat down to the Indian food she learned to love during a stint in that country. Almost all the ingredients came from Ann’s garden in the front yard—or from the chickens we can hear clucking out back.

Even as a middle schooler, Ann liked to “talk politics” with Bob. High school boys, worried about being drafted into the Vietnam War, found Bob willing to counsel them about what their options might be. Bob gave Ann books to read. One of them was And Quiet Flows the Don which detailed the horrors of WWI as well as the Russian Revolution and civil war. “It scared the shit out of me,” she said.

“My time in the Party began during middle school,” Ann continued, “but it was more the people than the Party.” Through the Plajas, Ann met Hortense Allison, Bob’s grandmother. Ann understood “Grandma” Allison to have been a “higher up” in the Communist Party USA. Many years before, she was a leader in the Socialist Party of America in Seattle; later she was an official in the CP National Committee and a founding member of the US Peace Council among other roles.

There were meetings at Hortense’s house on Percival across Harrison. Bob’s cousins Donna and Ramon lived over there too, near the co-op. They were “red diaper babies” [kids born to communist parents]. It was a “red diaper community” around them.

Bob’s Aunt Helen, another relative and long-time Party official, brought stories from the national Party leadership in New York. Aunt Helen was a listener, Ann said, introducing them to books on US history by Herbert Aptheker and others, as well as antiracist and labor books from the Party book store in Seattle.

“The Party people were the only ones who consistently linked race and class and I was attracted to that. Those people and their ideas helped me answer big questions I had at that age: why aren’t people nicer and what about fairness? I found them sympathetic because their values were consistent with the ones I had come to.”

For Ann, the Party people she met had more energy, more optimism, more discipline. They were lively and interesting. “They knew how to behave in a meeting, how to be organized. They were trying to teach you to be a good member of the team. It was like sports, with a work ethic but a different goal. We were in it for the long haul, not just to win (or lose).”

The summer before Ann entered high school was a crazy time. A crescendo of opposition to the Vietnam War and everywhere demands for liberation. The Plajas had moved out to a farm they co-owned near Satsop where one day Bob was approached by a concert promoter for the Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races. The rock festival took place over Labor Day weekend in 1971 and it was big: Country Joe MacDonald, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Ike and Tina Turner, and more!

Ann remembers working the gate and running errands, meeting Billy Preston backstage, helping out a guy with a head gash from a knife fight. The State Patrol put peak attendance at 70,000 . . . only reduced on Sunday when a rainstorm turned the muddy field into a quagmire.

In the fall, Ann started high school where she joined Future Farmers of America, and was a straight-A student. She continued going to Party meetings.

What kinds of things did they do with the Party? During the oil crisis (OPEC) they passed out flyers in front of SeaMart. The flyers were about inflation and the harm US economic policy did to the working class, pointing out that inflation isn’t the fault of working people, but of the profiteers (remind you of anything?).

Mostly they followed the lead of the Seattle people. They participated in labor, civil rights, and antiwar demonstrations, and joined actions with comrades from Grays Harbor. She fondly recalls Brick Mohr’s stories of the International Woodworkers of America, and those of the many veterans and supporters of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade that fought the fascists in Spain.

How does she sum up this part of her life?

“When it comes down to it, what I got out of the Party was meeting and engaging with the most energetic, optimistic, warm and hardworking people I knew,” she said. “I had learned some leadership skills in my time in 4-H and the FFA along with public speaking. But I learned more through the Party. You didn’t flake out. We had constant debates. Hortense had a saying: look right, behave right. You learned how to comport yourself, how to present yourself. The goal was to get people to listen to you, to give credence to your position.”

Ann graduated from Olympia High School in 1973, but she effectively “dropped out” in her senior year and worked half-time in a lumber yard.

After a stint at the lumber yard and a winter trip to India and Nepal, Ann left Olympia to go to Washington State University. It was the obvious choice because of her interest in agriculture, but she found her ideological home there in the YWCA, “the most radical group on campus,” whose one imperative was to eliminate racism by any means necessary.

Bethany Weidner has lived a block from Ann and benefitted from her friendship and counsel for over 20 years.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer