FOOD

Making Hay While the Sun Shines

By Joe Tougas

Cold Comfort Farm took the “Farm” in its name seriously. We thought of ourselves on the model of agricultural co-ops. We wanted to be independent, creative, revolutionary. We were pretty smug about our agrarian accomplishments. Although our knowledge of small-scale farms was spotty and romanticized (not to mention borderline illegal) we were proud of our worn-out overalls and home-grown strawberries and broccoli. Our most ambitious ventures were in the field of animal husbandry. We kept a couple of goats, dozens of chickens, a couple of barn cats (outdoor only), a flea-bitten German Shepherd, an indeterminate number of rabbits, a horse or two, a lamb and its mother, some geese to act as security patrol, and, unwisely, pigs.

The animal population would fluctuate seasonally. For example, the new batch of chicks would arrive in the early spring, and they would go into a large cardboard box in an out-of-the-way corner with a 15 watt bulb. They were sexed, sort of, and quickly grew to the size of pigeons. Soon it became clear that the chicks were not all female. At that point the season of killing began. A litter of kittens here, a lamb there . . . It’s called “culling the herd.”

Thus we came to understand the amazing—and terrible—fecundity of life by which farmers through the ages make their living, and then share their bounty with the rest of us parasites. Every generation needs a few girls and boys who stand ready to play the role of gatekeepers to the idyllic life of the barnyard. And these children, soon to be young farmers, need an older farmer to wield the knife and shovel, a mentor who is wise in the ways of country life, willing to share that wisdom with those new would-be farmers who are just coming along, whether they were long-haired and bearded, or straight-laced and devout. One such mentor was Henry Winn.

“Hank” was a hay farmer who lived between Olympia and Shelton, at the end of Whitaker Road. Judging from the outbuildings totally buried in twelve foot high blackberry brambles and the rusting hulks of antiquated farming equipment, this was obviously a family enterprise of several generations now in decline. And Hank was in need of a younger recruit to keep the place going into the future. “I ain’t getting any younger,” he often said over a glass of sweet wine. There were several houses on that road, and Hank’s sister, brother-in-law, as well as several nieces and nephews, shared fragments of the family homestead. Most of them shared the family name. None of them seemed to have any interest in raising calves and repairing old tractors, not to mention hoisting 60 pound hay bails.

But the times they was a-changin’, and those changes were disrupting the usual pace of life in this corner of southwest Washington. You could hear a kind of curious unease if you paid close attention to what people were talking about in the older, established shops and businesses. You might hear worried conversation at the local tavern, a place called Character’s Corner at the intersection of Whitaker Road and Highway 101. One way or another the word got around that there was a bunch of hippies who had moved onto a piece of semi-forested land not far down Bloomfield Road. The consensus at the bar was that this was part of the flood of students who had been attracted to the area by the new college that had just opened. There was the expectable gossip about how the newcomers might behave, dress themselves (or not dress themselves), and what their coming might mean for property values. Over the course of several weeks that topic had more or less run its course, mainly due to the lack of any new information about the counterculture invasion.

But then one evening one of the regulars at the tavern showed up with some fresh grist for the conversation mill: one of the local farmers had been approached by a young couple inquiring about buying some bales of hay. Apparently they were planning to raise goats. That farmer had to give them the disappointing news that he had sold off the last of his hay, and that he wouldn’t have any more until the new crop was cut and baled. He was, however, able to tell the young folks that he thought that old Hank Winn still had a few bales in the back of his hay barn. Country folks keep track of such things. The next evening Hank showed up at the tavern with a big smile on his face. This was not an everyday occurrence, since Hank was a pretty low key individual. “Heh Hank, you look like the cat that ate the canary. I think you must have made a fortune in the hay market today. Shame on you if you just took advantage of a couple of starry-eyed would-be goat farmers, selling them straw for alfalfa.”

“No, actually I gave it to them cheap on account of it being the last of the old crop. No, I’m not smiling because of last year’s hay, I’m smiling about this year’s. I think I just hired me a crew to help with this year’s baling.” Now all I need is a week of good weather.”

“Ya, well good luck on that, buddy.”

One of the “starry-eyed farmers” who actually knew a thing or two about farmers was Mike Nordstrom, aka “Wyoming.” As the nickname suggests, Mike was a country boy. Mike had a sincere love of hard outdoor work, topped off at the end of the day with a glass of wine, sitting on the porch, watching the sun go down. He soon became good friends with Hank, who could provide the three essential ingredients: the porch, the work and the wine. Hank’s hay crop that summer was excellent, both in quality and quantity.

Mike could recognize the challenge Hank was facing. In order to have a successful year Hank needed to get his fields cut, baled and stacked in his barn when the moisture in the bales was just right. An untimely shower, or even a couple of misty mornings could cause mold which could decrease the value of the product. Worse, it could cause fermentation of the hay, which could generate enough heat to cause spontaneous combustion and a fire that could destroy the whole place. As Mike and Hank sat together that hot August evening they had no need to discuss or even mention the perennial dangers facing farmers. They had more interesting, and more exciting things to talk about. At 6 a.m. the next morning the baling would begin. Over the past several days, Hank and Mike had gone over every piece of equipment that would be needed to do the job—the New Holland baler, the tractor, the lowboy trailer, the electrical conveyor belt, the hay rake, etc. Mike had noticed the previous day that Hank had neglected to purchase the big spool of baling wire. After a few words to Hank, he sped off to the farm supply store and came back spouting jokes about how the whole thing could have “gone haywire.”

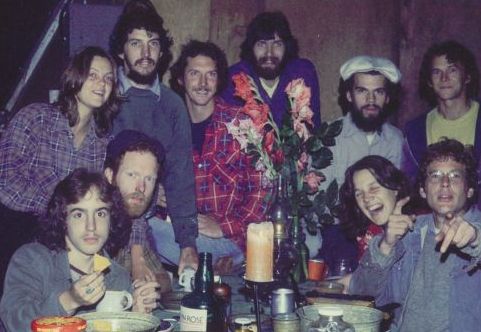

Hank was especially excited about the crew from Cold Comfort that would provide the manpower to get the bales onto the trailer and stacked in the barn. The gang consisted of Mike, Bill, Dan, Steve, and me. Richenda, Ernestine, Cindy, and Fran would be arriving at noon with a big jug of iced lemonade, a large roasting pan of chicken and dumplings, and a huge salad, fresh from the Cold Comfort garden. As we sat down to eat there were no snide remarks about that slice of bourgeois Americana—we looked like a Norman Rockwell cliche of a day on the farm, with the men and the women playing their stereotypical roles. We were hungry and the food tasted great. We knew that at the end of the day we would have another great meal, only with beer instead of lemonade for the first course.

By the middle of the afternoon Hank knew that he had made the right decision in hiring the “hippie crew” as the guys at Character’s Corner insisted on calling Hank’s scruffy-looking team. The following day was memorable for several reasons. Because we city boys were not accustomed to working long hours under a blazing sun, didn’t deign to wear hats, had never understood the importance of sunscreen, we all showed up the next day with roaring sunburns. We jokingly called it “The day of the lobsters.” Another unusual feature of that next day was that, while we were eating our lunch the television was on in the living room. This was an unexpected sight on a farmhouse in the middle of the day in the middle of haying season. As we entered the house and heard the voice of Walter Cronkite we realized the significance of that occurrence: it was August 8, 1974, the day of Richard Nixon’s resignation.

As we were finishing the work for the day the cold water showers felt soothing to our sunburned necks and arms. We could hear “the girls” coming up the driveway laughing. They were carrying large baskets and jugs, and a couple of six-packs of Olympia beer. We could see slight purple stains around their lips and on their fingertips. The dinner was a down-home banquet. Pork chops, potato salad, apple sauce, home-canned dilly beans, and another big green salad. As good as the meal was, our eyes kept wandering back to the two big round platters and the women’s stained lips. At last, the dinner plates and leftovers were swept away, and the covers on the round platters ceremoniously lifted to reveal two fresh-from-the-oven blackberry pies. Mike commented, “I guess we know what you all were doing while we were working away in the hot sun. I’m wondering if there are any of those berries left on the vines.”

Ernestine said, “We were not just eating blackberries. We were working too. We were studying—Evergreen style.”

Fran said, “I was working on an archaeological survey of a late Pleistocene settlement. We found an amazing Neolithic tool that seems to belong to some ancient civilization.”

Richenda added with a twinkle, “It looked a lot like a rusted socket wrench.”

“And you had to tunnel into that bramble of blackberry vines, to that shady spot in the middle, right?” said Mike.

“Right to where the berries are the sweetest,” said Cindy, “and you pathetic rednecks get the benefit of our hard work.”

“Well, I can hardly wait to read your narrative evaluation of that “school work,” said Dan, putting the last two words in air quotes.

Ernestine broke into a fit of laughter. “Will you dopes stop your fucking bickering and dish us up some of that pie.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer