HOUSEHOLDS

Life on a Hippie Farm

By Anna Schlecht

When I first came to Olympia in the mid-1970s, I was enchanted by stories of the early days of The Evergreen State College when many of the first students lived in tents and DIY cabins in the woods surrounding the campus.

Cabin-dwelling sounded like the perfect life for me. Somehow, I heard about IOCWAT Farm (In Our Community We Are Together) from one of the residents who rolled through my check-out line at the downtown Food Co-op. Or perhaps I found a flier about the farm with a tear-off number to call. How ever it was I found the farm, moving to this rural commune began my chapter of living off-grid.

Touring with Mingo

I can’t remember if there was any kind of application process. Most likely, it was a simple interview with the owner, a widowed woman named Peg Wortman, although everyone called her Mingo.

“Tell me all about yourself!” she implored, with a huge smile across her face. She had a magnificent mane of hair that doubled as an aura, almost sparkly with energy. Mingo was a remarkably good listener, a useful skill to figure out who she wanted on her farm.

During this first chat, she radiated interest in everything I told her about my life and why I came to Olympia. As I got to know her better, I saw that she did most everything with the same level of sheer delight–meeting new people, tending to the farm, composing her thoughts on a typewriter.

While she looked like someone from a middle-class house in suburbia, her actions proved that she was right at home in a commune. Her house was filled with the smells that clung to kitchens everywhere that hippies made food. Apparently, we all used the exact same spices from coast to coast.

After chatting a bit, Mingo took me on a tour of her farm, following a well-beaten path through trees that surrounded the main pasture. As we walked, she explained the origins of the acronym IOCWAT and what this rural community was all about—basically, a hippie farm. While there was a large garden, the real crops were all kinds of crazy dwellings.

As we walked along, she told me the story of each structure and the amazing people who had lived in it. Most of the residents either were or had been Evergreen students, and each of them seemed to be an artist of some sort–actors, musicians, painters, or sculptors. At that time, most of them were involved in an Evergreen program called Chautauqua. As one of Evergreen’s famous interdisciplinary courses, it allowed students to explore the history, politics, and folk practices of community-based performance art.

In between tour stops, Mingo explained that this was her family home, but since her husband had passed away and her oldest daughter was gone, she had created a new life. She and her three younger children lived in the main house surrounded by pastures and woods. From the house, you could see the barn and a few other outbuildings. Just beyond the tree line was the rest of her village.

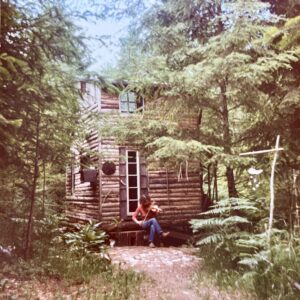

Mingo’s woods were a hushed wonderland with fairytale-like dwellings, hugged by dense underbrush and surrounded by moss-covered trees. The dampness in the air seemed to be one of the many filters that kept out the air pollution that was so rife in the cities. It was astounding to think people were living in this forest, even more so that I would soon become one of them.

An adventure in this forest community

Residents paid a nominal rent, scaled according to the stage of completion of their structure. We could live in our respective dwellings as we found them, or continue to build out the structures or other whimsical creations. My favorite such creation was an outhouse that had a roof and a window but no door or walls, something that offered amazing views but zero privacy and little protection from the weather.

My first accommodation at IOCWAT farm was a tipi, an indigenous dwelling originally from the tribes of the Great Plains. Hippies borrowed liberally from any culture, now understood to be co-optation by those of us who were not part of those cultures.

Whoever put the tipi up did a good job of stripping bark from the poles and stretching canvas across the frame. Still, my sad little tipi was dreadfully ill-suited for a rainy climate, even after I modified it with a patio umbrella that I found at a junk store downtown.

My tipi was also infested with mice. Late at night, they would run laps around the inside periphery, competing in some kind of rodent rollerdrome. One night, one of them got entangled in my massively curly hair. After shrieking and shaking the mouse loose, I pulled a wool hat down to my nose for protection. Unnerved by my unwanted roommates, I slept with that hat on every night thereafter.

On another fateful night, the central wood stove melted my sleeping bag, though fortunately did not set it ablaze. This stove offered little protection from the elements, with the chill and humidity coming through the canvas walls to infuse my dreams. Somehow, I survived the winter.

We residents were invited to participate in caring for the livestock and gardens, which also meant sharing in the bounty of milk, eggs, and vegetables. Mingo’s farm had one cow, occasional steers, several goats, and a huge garden. Every day, there were eggs to collect, weeds to pull, and a cow to milk.

I wrote home about all of my adventures, especially about how I learned to milk a cow named Mollie. I had the evening shift, and each night all the farm cats would appear, hoping to get some milk. I never managed to squirt milk right into their mouths, but they seemed happy enough to lick it off their fur.

An exciting challenge

My letters home also shared tales of helping my neighbors build new homes out of logs straight from the woods. That required felling the trees, stripping the bark, and taking some of the logs to get ripped into siding. I thought this was all a remarkable accomplishment, far more important than going to college.

My mother wrote back, only partly joking, saying, “This is just great. Our family leaves the back-breaking farm life in Europe, comes to the new world to start a new life, all for you to move back into the 1800s to live in a tent and milk a cow!”

Some of the cabins were conventional looking, others had impossibly fanciful designs. So impossible in fact, that they remained incomplete with gaping holes barely covered by plastic sheeting. While I first thought I was surrounded by architectural geniuses, I soon realized most of them were big on ambition but light on skills.

Building was fun, and finding materials for free or cheap was an exciting challenge. My newfound friends gave me the lowdown on where to find building materials, none of which involved conventional retail. Perhaps because many of them were artists, they insisted on drawing maps to help me find my way. Most of the maps featured long, windy roads between creative interpretations of things like “the water,” characterized by waves filled with bizarre sea creatures. A central feature of all these maps was Spud and Elma’s Two-Mile House, apparently the center of the universe, portrayed as a roofed box with a beer mug inside and happy people whose overflowing hair spilled out of the windows.

Hunting and gathering

My first hunting and gathering foray took me downtown to the waterfront, where an ancient pier was being demolished. I could hear seals barking in the water below and seagulls calling in the sky above. It was vastly different from growing up near freshwater lakes. Looking around the pier, I found the head guy in charge, and he told me, “Take all you can salvage in an hour for five bucks. Don’t fall in.”

That seemed fair, so I got to work with my borrowed crowbar and pulled up about twenty planks of salt-cured two-by-eight tongue and groove decking. I was so pleased with my stack, I didn’t realize that half the work was pulling it up, the other half was figuring out how to stack it on top of my car. My Rambler Classic must have been quite a sight driving slowly up the Westside hill, with my precarious load of wood up top.

I was proud to be one of the many people keen to find and reuse building materials, later known as “up-cyclers.” There were many of us who scoured the alleys, searching everywhere to find plywood, sinks, etc., all free of charge. Our farm was one of several where the dwellings were constructed of twice-used, sometimes thrice-used building materials. This ethic was something I learned early on from parents of immigrant stock raised in the depression era.

Eventually, I got my planks cut and nailed down to expand my tipi platform. This was my one and only contribution to the built environment of the farm. As light rain fell, I imagined how nice it would be to sit out there in sunny weather. After a few weeks, I realized that sunny weather was not likely to arrive for months. As the winter days got shorter, my nights alone in the tipi felt longer. It was time to relocate.

A Cabin for One

Eventually, I moved into a vacant cabin, a simple structure with one main room and a pole ladder up to a sleeping loft. The siding was irregular boards called live edge slabs that were ripped from sides of logs, pretty to look at but filled with gaps. Here too, I had plenty of mice for neighbors, always quite industrious at night. Fortunately, they stayed down next to my food and I stayed up in the loft. The interior was warm and relatively dry while the wood stove was blazing, but as soon as the fire died down, my cabin was as cold and damp as sleeping outside.

One unique aspect of living deep in the woods was the common practice of walking in the dark. When the moon was out, it was easy to discern the trail from the brush. On moonless nights, my feet had to remember the way. Somehow, that felt like a rite of passage, officially marking me as an outdoors woman.

As spring came, everyone’s spirits started to lift. Our parties went from grim little gatherings in tiny, damp cabins by candlelight, to open-air events lit by lanterns strung from tree branches. The Chautauqua people knew how to party! The lack of electricity meant no canned music. Instead, they would take turns entertaining us with songs, dances, and bizarre monologues. My best contribution was that of an enraptured spectator.

By fall, I decided it was time to move closer to town. Although I had loved living among artists, I knew I didn’t want to face another winter on the farm. While all of them were politically aware, none of them seemed to be political organizers, and few of them were gay. I knew there were more of my people I still needed to find, so I moved on.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer