WORK

How a Data Report on Racial Bias in Corrections Affected My Career

By Pat Holm

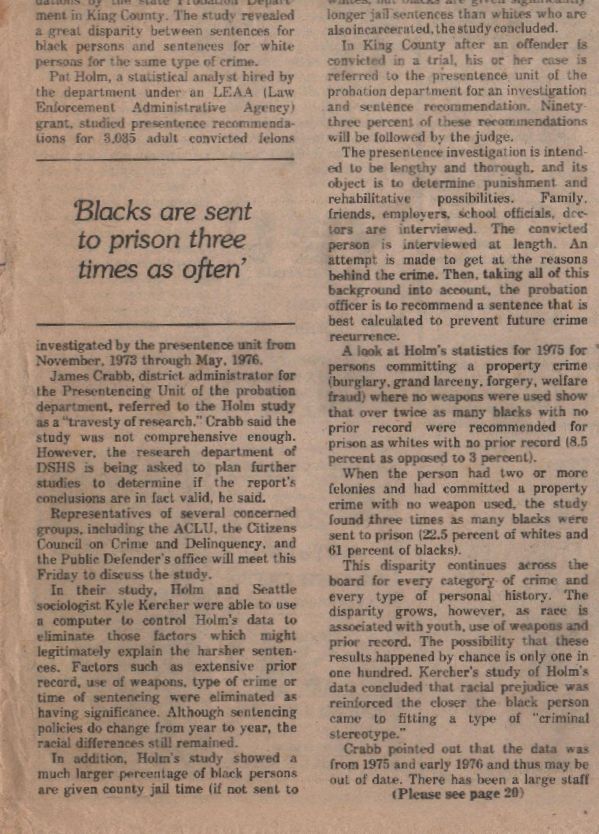

One of the biggest accomplishments in my working life was sharing my controversial findings on correctional data with the press. Headline in the October 26, 1977 Seattle Sun (an alternative newspaper): Study says white felons favored.

Writing a 30-page article (mostly graphs) from my work with the Washington State Department of Corrections (DOC) occupied most of my summer in 1977 while I lived on a boat moored on the Ship Canal in Seattle. The data clearly showed the unequal treatment of Black men. I took a six-week leave of absence from work to do the writing because I wanted to make sure that people understood that I did not do this writing while being paid by the state. I had tried to get my supervisor to allow me to put this information into the official reports for Law Enforcement Assistance Administration (LEAA) and Law Enforcement Criminal Justice, but Joe Lehmen, my boss, would not allow me to do that.

I felt that since I was the only person who knew about these discrepancies, morally I should make these facts known to the public. On June 20, 1977 I also was given notice that my job would be officially over in September 1977 as the LEAA grant was ending. I wasn’t given the option of another position with the department at that time. Although, before the story broke in the newspaper, they would have found a job for me in one of the Seattle offices. I had received lots of praise for the quality report I put together for LEAA looking at the Pre-sentence Corrections Unit in Seattle which was implementing a new emphasis on community programs versus jail or prison time for felons.

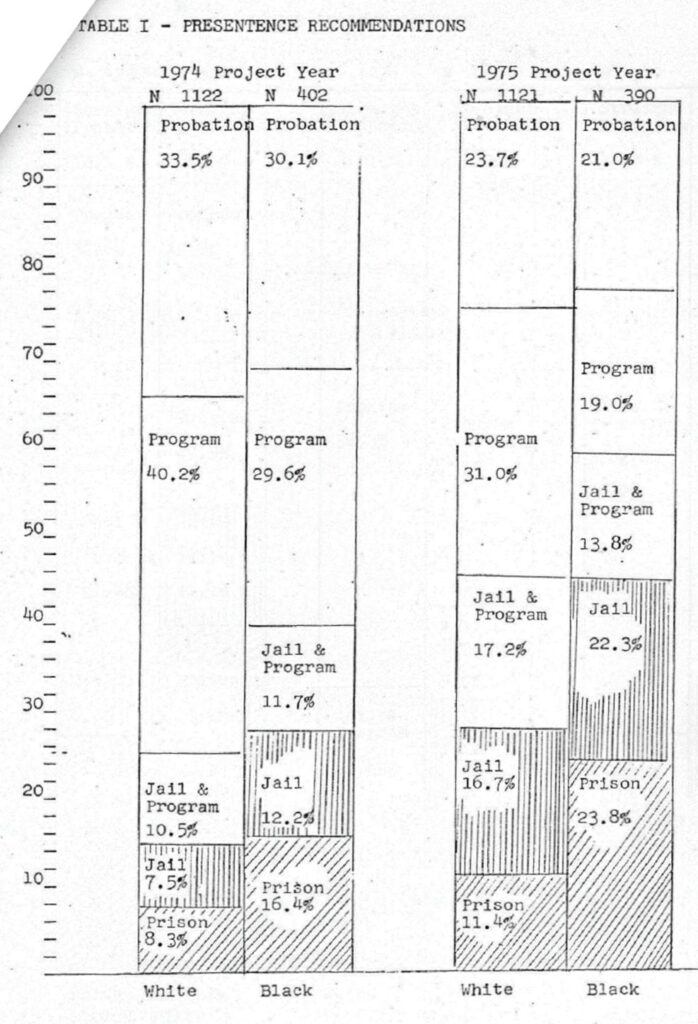

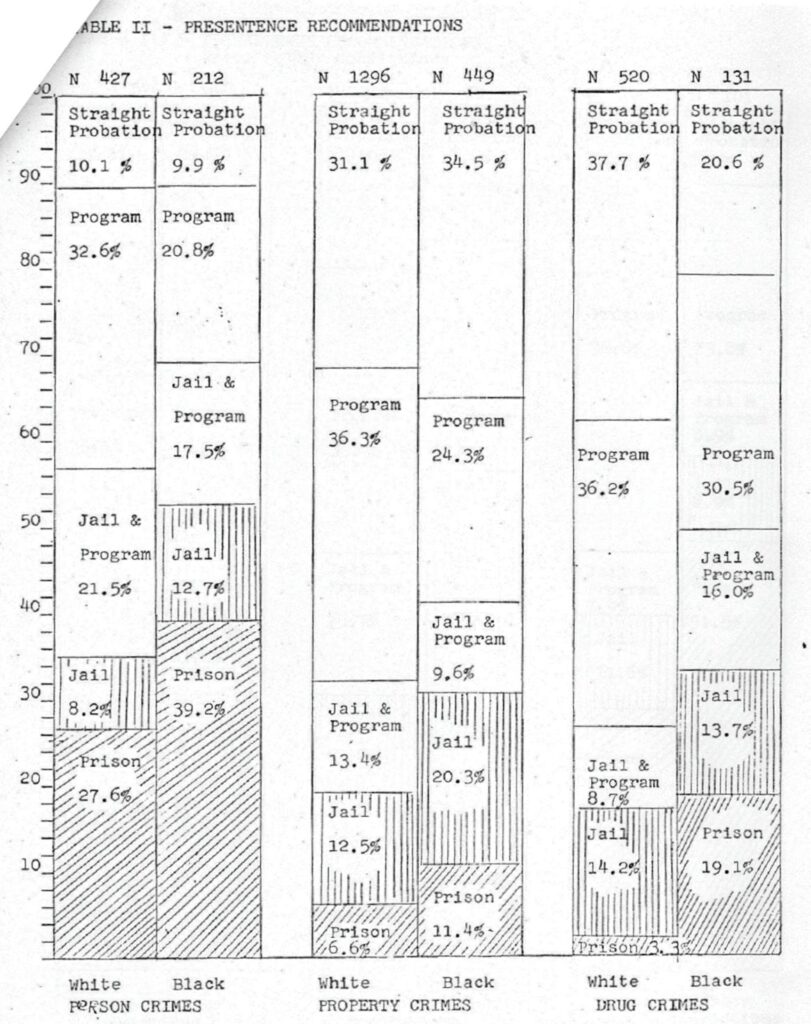

My research looked at how many times the probation unit recommended a program and how often the judges agreed with their choices. There was a very high correlation, in the upper 90% percentiles, between what the probation officer recommended and what the judges sentenced the men to. Many more White men received a community program, while most Black men received jail or prison time.

Going back to the beginning of how all this happened

In 1974, I was hired for a temporary DOC research project in Seattle to study community-based programs and whether those participating in a program would have less recidivism (committing additional crimes after being released) than those going to jail or prison. I was already working for DOC in Olympia. This new position would allow me to return to Seattle for three years and it was a promotion. I jumped at the chance. Kirsten, my daughter, was 16 at the time and I thought she would be okay in Olympia with a roommate or two from The Evergreen State College. I rented a room in Seattle at first as it was just me moving there. I didn’t have to have a car there and could take the bus to work at the Smith Tower. Steve Wilcox kept the Maverick and could come to see me.

The research job consisted of creating a questionnaire with pertinent questions, reading each file of each man who came through the program, filling out the questionnaires, taking them to the University of Washington (UW) to have the data punched up on cardstock to eventually be put into a computer, and retrieving the data from the computer. I was the sole researcher, so I had a lot of control over the project. Later, probably year two, my supervisor hired a person to help with gathering the data and transferring it to computer cards.

After the project was finished and I had written up the findings, I was invited to give a presentation at a conference in Washington, D.C. in February 1977. I flew there to give my talk and shared a room with JoAnn Ray, who was also a researcher for LEAA from Spokane. She became my best friend for over 40 years. JoAnn encouraged me in so many ways. We shared many of the same values. She and a friend, who taught in the Social Work Department at UW, introduced me to a group of folks who were working on corrections reform in Seattle. Their group, the Citizens Council on Crime and Delinquency, the American Friends Service Committee, the Associate Council for the Accused, the ACLU, and the public defender’s office met with me and came up with these recommendations for making the situation more equal:

- Hiring Black staff to the Seattle Pre-sentence Unit, as there were none at that time (24% of the client population in Seattle was Black)

- Training for existing staff on racial awareness

- Feedback to the unit on equal treatment

- More employment programs

Only 5% of the community treatment programs were employment programs, whereas 62% of persons investigated were unemployed (10% more Blacks than Whites). There should be more employment programs to deal with this fact—even 40 years later. Having a job is still a very important part of staying out of prison or jail.

I gave a talk in April 1977 at Pacific Lutheran University (PLU) with the topic “Economic insecurity and crime: the need for employment programs for felons.” For the UW social work class on unemployment issues I gave a similar talk about what I uncovered in this three-year study of the pre-sentencing unit in Seattle. A total of over 3,000 adult men went through that system from 1974 through 1976.

I was pleased that the DOC upper level staff did follow through with hiring more Black probation and parole officers soon after the findings were made public in 1977 in the Seattle Sun. I had become friends with Julie Kesler (who wrote the article) a year earlier to acquaint her with understanding the study.

I wrote up the report on an old typewriter on a small dining table on my boat. This was before computers made graphing easy. I used graph paper and carefully constructed over ten graphs showing the results of my data. I carefully cross-hatched, made dots, and various ink lines to show the different results. I included two of the graphs here. The number of men in each group is shown by the letter “N” at the top of the page.

I am proud of that work. It took discipline to stay with it and finish the paper. This paper and the story in the Seattle Sun pretty much destroyed my ability to ever get another job in the DOC research shop, however. I had tried getting the attention of my supervisor and the bosses above him about what I had discovered. But unequal treatment of minorities was not anything they were interested in, that is until I went public. So, in many ways I do not regret that I did what I did.

I was treated terribly by my fellow researchers in the department. They said awful things in public about my research skills. Later they asked me out to lunch as though nothing had happened. My boss, who I had been working with for three years doing this research, had praised me highly in my employee evaluations, and I received high marks from LEAA, who had paid for the research study and invited me to present my findings to a conference in Washington, D.C.

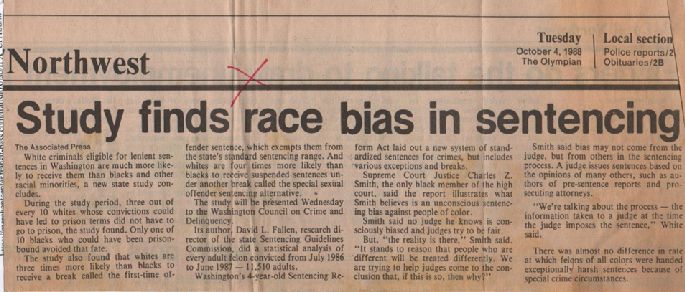

David Fallen (not one of my friends), who later became the research director of the Sentencing Guidelines Commission, criticized my report sharply. Yet ten years later, he conducted a similar study that showed racial bias against Blacks. At that time the department didn’t have the information that showed how closely the judges aligned with the pre-sentence unit recommendations, but they speculated (based on my report) that was where the bias came from. I kept the article that detailed this finding. It was an Associated Press article on October 4, 1988, that appeared in the Daily Olympian. The headline was: Study finds race bias in sentencing. My report had not gone unnoticed.

Another article that I saved was from the Seattle Times, November 30, 1980. Its headline was: Experts puzzled: Why does Washington State have top Blacks-in-prison ratio? The article explores in less detail than my paper had the reasons why this was so. This article basically used population statistics and prison numbers to ask the question: Why are Blacks 22% of the prison population but only 3% of the overall state population? They did not report my data which clearly showed that Blacks got more jail time initially, were interviewed by the pre-sentence unit while they were in jail, and fewer had jobs, which was where part of the bias came from.

After a year went by and my unemployment ran out, I was ready to come back to Olympia to find work. I realized from my employment search in Seattle that Olympia was about the only place that was hiring research folks. My 30-page paper (unwanted by my supervisors) was noticed by Merritt Long, who was starting up a new state program called Corrections Clearinghouse in 1976. Corrections Clearinghouse (CCH) was funded by the Washington State Department of Employment Security. The state did have a commitment to preparing offenders for the workplace and finding employment for minority ex-offenders. I started work there as a research analyst in May of 1978. Merritt was Black and Vince Ortiz, his assistant, was Hispanic.

“Life is what happens to you when you are busy making other plans”

– John Lennon

My job history seems pretty spotty, especially when I look at what I wanted to do when I graduated high school, which was to become an actress on Broadway. That didn’t happen because of an unplanned pregnancy.

Since my BA was in English literature and teaching, you might be wondering, why did I qualify for a statistical research job in the first place? Well, when I went to school at the UW in 1959, I worked at the new computer lab. First I was a keypuncher. We prepared the data cards that would later be used by the large computers. After working there a while, I learned how to wire the boards to program the computers. I was familiar with computers and how they worked. I had always been good at math and logic. Both my ex-husbands had jobs doing research so I knew what was involved and felt I could do it. An old friend who knew my background connected me with the research shop at DSHS where I worked for a while. I learned to write programs instead of wiring the boards (similar work) to get the computer to execute programs. Not many folks had that type of computer experience in the 1960s. I worked there for three years. I remember liking my job because I could use those skills.

Then I went back to the UW and got my fifth-year teaching degree in 1969. I landed a job teaching alongside Bob Gillis and Glen Munger in Elma. Carpooling with them made the daily commute from Olympia easier, but after a year and a half I wasn’t enjoying it. I got together with Steve Wilcox and decided to “tune in and drop out” with him. A year of that and I was tired of living with little money. I noticed in the newspaper that Nixon had continued Johnson’s war-on-poverty job program. A research analyst position was available at DSHS if I applied through the job program, so I hurried to apply the next day and I got the job. It was this job that got me my promotion to Research Analyst II and the LEAA research position in Seattle in 1977, and ultimately my research job at CCH. However, I lost the position with Merritt Long for being insubordinate (I thought I knew more about corrections data than a person he hired to be my boss).

Then I got a position under the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) for six months but really didn’t understand what I was supposed to do or how to do it. The day I got fired from CETA I went to lunch at the Herb & Onion (later the Urban Onion) and while waiting in line to order my food, I stood next to my future boss. We started chatting and I told her I had just gotten fired. Somehow it came up that I had a teaching certificate which was good for all teaching levels. She was looking for someone to teach English as a second language and offered me the job. I taught at North Thurston H.S. for six months and then I moved up to teaching adult ESL at the community college. Teaching adults agreed with me, and my boss appreciated me. So did the students. I taught there for seven years until I decided to go back to school again, this time to get my Master’s degree. Whenever I didn’t know what to do next, I usually went back to school. I liked being a student and learning new things.