ACTIVISM

From Here to El Salvador

By Beth Hartmann

I was sixteen when I went to my first antiwar demonstration in 1967. I lived in Los Angeles in “The Valley” and hitchhiked with my friend over to Century City where LBJ was staying at the Century Plaza Hotel. The march seemed huge, so much energy, all kinds of people from all over the city including tots in strollers and kids on shoulders. After a while we came to the front of the hotel where lines of police guarded the entrance and a loud speaker instructed us to keep moving. We did not keep moving. The lines of police moved forward, billy clubs swinging. It’s the parents with the strollers trying to get away that I remember.

I lived in a very conservative Christian suburban family thick with dysfunction and hypocrisy. I found my people in the coffee houses of West Hollywood, read the L.A. Free Press, and developed my world view as my identity was forming. I learned enough to believe deeply that the war in Vietnam was a travesty that we as Americans had an obligation to resist. Like for so many of my generation, this was the foundation of our culture of dissent.

Flash forward to 1979. The Vietnam War has ended. I had been involved in protesting nuclear weapons, working on food justice and sustainability issues, living and working collectively. There was a faint buzz about Central America but nothing big in the news, nothing to capture my radical imagination.

My friend John was in Seattle and attended a meeting of the Committee In Solidarity With the People of El Salvador (CISPES). He came back with emotion in his eyes and immediately arranged for a presentation to be made in Olympia. The meeting opened with a short film. The footage was horrific. Maybe you’ve seen it. At the funeral of martyred Archbishop Oscar Romero, the army opened fire on the crowd as they left the National Cathedral on the main square of the capital. There were stories told by people who had become refugees as the army destroyed villages in the name of counterinsurgency.

The U.S. military was up to its eyeballs in all of this, marching alongside Salvadoran soldiers on forays under the auspices of advisors, training Salvadorans at bases in the U.S., meddling in the affairs of a Latin American country as we have notoriously done for so long in so many places.

At home that night, the war was present in my mind and my dreams, the images and stories haunting me. I wasn’t the only one. We were soon meeting and talking about how to organize in support of the poor of El Salvador and confront the policies of our own government that perpetuated rampant abuses. No one envisioned an antiwar movement like we had with the Vietnamese War. This was a tiny country and U.S. involvement was hidden and more subtle than boots on the ground, though there were boots on the ground in some cases.

It wasn’t long before a lot of people were involved. The work broadened to include Central America, especially Nicaragua where a democratically elected government was under attack with covert but widely known U.S. support. We organized educational events, including visits from activists from Central America. We lobbied our representatives and even senators about how U.S. actions were supporting oppression and violence. We worked with Amnesty International to help free political prisoners, not without success.

There was so much going on at this point, in Central America and in Olympia, that it was clear that a regular source of information was needed. There were a number of us ready to take on this commitment. As with so many publications, fliers, and posters in those years, little would have been possible without Hard Rain Printing Collective.

I can see that stairway now, a wide climb up to the second floor of a building on Washington and State downtown. Upstairs was the print shop with the smell of ink and other printing chemicals. There was a customer service counter, shelves of paper and other paraphernalia of the work, a wall of light tables for doing layout long before computers, and a great old offset printing press built of cast iron and a million moving parts that were mastered by Grace Cox.

I had no background in writing or design but was willing to learn. Luckily there were those willing to teach. I went to the library every few days and scanned The New York Times, Washington Post, and The Guardian for any reliable news about Central America. There was also In These Times as well as newsletters and PSAs from our sister organizations. All of this I would compile into articles. Everything I know about editing at this point in my life I learned from Don Martin there at Hard Rain. Once we had our content written we would type it into columns and use press-on letters to create headlines. Then came the part I enjoyed the most: layout. Taking all of those little pieces of paper to the light tables and placing them on the pages. Sometimes we were there late into the night to meet our deadlines.

There is something incredibly satisfying about seeing those pages come to life in print. We had come to call our little newsletter Atento. We placed copies all over town and they were taken and presumably read. It seems like we must have done some mass mailing too, but I don’t remember that part. I do remember getting lots of positive feedback and thinking that a regular publication helped to strengthen the work that was being done.

One of the fun things about organizing in Olympia was when people just took it upon themselves to do little independent actions. One of my favorites involved bananas. The Food Co-op was getting bananas from Nicaragua. Olympia was hosting the first ever Women’s Olympic Marathon Trials. The scene downtown was festive at the lake where the finish line was. Anna Schlecht and I loaded up a red wagon with bananas and a big sign with the colors of the Nicaraguan flag and went through the crowd raising funds and awareness. Of course, we had plenty of newsletters and other literature to share.

I started organizing for Central America in 1979. In 1986, I had the opportunity of a lifetime. A large delegation of activists from across the country was being organized to go to El Salvador. Using the network of contacts I had built over the years, I was able to raise enough money to help with the travel and bring over two thousand dollarsa to contribute to our host organizations there. I also received a huge box of medical supplies that were left over when the women’s clinic closed.

It was a life-altering week in El Salvador. Every day was filled with meetings, mostly with activist groups but also with representatives of both the Salvadoran and U.S. governments. While we met with a labor organization, the “death squad” vans, black Jeep Cherokees with dark windows circled the building. We drove for hours one day out into the countryside to meet with people in a village who had survived an attack by the Salvadoran army. They had prepared an amazing meal for us in the midst of these circumstances. We were even unexpectedly given access to visit political prisoners in the most notorious prison. There we heard stories of torture but also endurance. They had a literacy program and a program to make crafts for people on the outside to sell so that the prisoners would have food and other essentials.

The highlight of the trip was the march. We were there for May Day of 1986. May Day is known in most countries as International Workers’ Day. In El Salvador it is recognized as a major event by both the left and the right. It turned out that this was a very special May Day. It was the hundredth anniversary of the event that started the recognition of International Workers’ Day. That event is known in this country as the Haymarket Riots in Chicago in 1886. I did not know this. It seemed like everyone in El Salvador did know this and there were signs and chants honoring “los heroes de Chicago.”

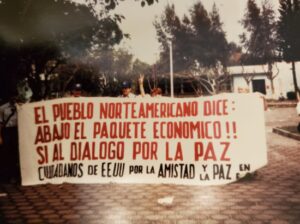

We marched with the student contingent in the May Day parade. One of our banners translated to “North Americans in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador.” Groups of people would see it and break into delighted cheers. We finally arrived at the center of the city, at the plaza where the military had years before opened fire on mourners at Archbishop Romero’s funeral. The plaza was crowded with people. There were speakers who I could not understand. At the exact time that the rally was to end, the plaza emptied as if my magic, as the perennial military presence retook the space.

When I returned from El Salvador I did some slideshow presentations wherever I could find an audience. I wrote a column or two for the Olympian. That week fundamentally altered me, but it was hard to see a way to put those new sensibilities into action. There remains for me questions about delegations like this, about the use of resources and the value to the cause.

I look at Central America now and wonder what was the use of all that work. We wanted to change the policies of our government towards the other countries in the hemisphere. The wars are over, but the people have not benefited. Now it is gang warfare that terrorizes. Now people who are able are coming to the southern borders of the U.S. in desperation. I volunteer with refugees now, not necessarily from Central America but sometimes. I tutor English and work with people who are trying to gain citizenship. They come from many countries. Many of them have waited for literally decades since they had to leave their homes. I wish there was hope for a kind of immigration reform that would address these problems, that would allow for us in this country to provide refuge, which we have the resources to do. In the meantime, I find some joy in being able to help one person at a time.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer