ARRIVALS

Fleeing Minnesota and Coming to Olympia – 1950s-1960s

By Pat Holm

I met my first husband, Ron Bodley, at the University of Minnesota at an anarchist meeting. I was studying theater and was in about three plays every quarter. I made the dean’s list after my first year. I got pregnant during the second quarter of my sophomore year because my mother let me live in town while I went to school. Okay, I suppose letting Ron stay the night might have had something to do with it. After I found out I was pregnant, I thought my parents would be upset, so Ron and I ran away to Seattle where he had a good friend who could help him get a job. It was 1957.

Our Socialist group in Seattle met at the Unitarian church every Sunday night in the U District. There I learned about the Canwell committee that was bent on rooting out “communist” professors at the University of Washington. Professor Rader, who taught philosophy, had been part of this persecuted group. He was a Unitarian and a member of the ACLU. I was able to sit in on Rader’s classes on aesthetics in which he shared a lot about his being caught up in that fracas. He was one of the professors who almost lost his job because of his socialist activities. Years later, he was able to prove that he was not a communist. Most jobs with the state in the 1950s required you to sign a loyalty oath to the USA to be considered for hiring. In 1962, a group of 64 faculty, staff, and students at UW filed suit to stop enforcement of the university’s mandatory loyalty oath. The oath didn’t go away until almost 1964.

While in Seattle, now with my daughter, the socialists were my friend circle. I left Ron due to his drinking and went to live in a communal living situation. I finished my schooling with a degree in English literature and a teaching certificate. About that time, I met Pete Holm, left my communal living arrangement, and married him. Pete got a job at Boeing but was fired soon after he started working there. I had to find work to support us . . . which took us to Centralia because I couldn’t find a teaching job in Seattle. I taught high school senior English and directed the junior and senior class plays (Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest, and Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People).

Pete got a statistician job with the state, and when my first year of teaching ended in June of 1963 we moved to Olympia. I didn’t know much about the greater Olympia community. We had been driving to Olympia on Sunday mornings from Centralia to attend the Unitarian Fellowship. When we moved to Olympia, the fellowship became our friend group. About 40 families were involved.

The Unitarians were interested in politics and a more just society. Also, it was a unique mix of social classes. Barney Bucove was the director of the health department and a close neighbor. Lois Bergerson was a nurse. Betsey Mcquire was the director of Head Start at the time. Sally Giovine was a single mom with five boys (her husband had died of a sudden heart attack and we became very close friends). And us–we were previous beatniks, now calling ourselves hippies. I did collaborative performances with a ballet teacher. She danced while I read modern poetry. I wrote and directed our Christmas pageants at the Fellowship for three years. I loved being invited to dinner parties at Betsey’s house. Coming from a working-class background, fancy dinner parties were not part of my history. Those parties were a unique experience and very exciting to me. The Unitarians considered us as equals at their table. Our kids played with their kids. Pete taught Sunday school at the Olympia Women’s Club which the Unitarian Fellowship rented for Sunday morning services.

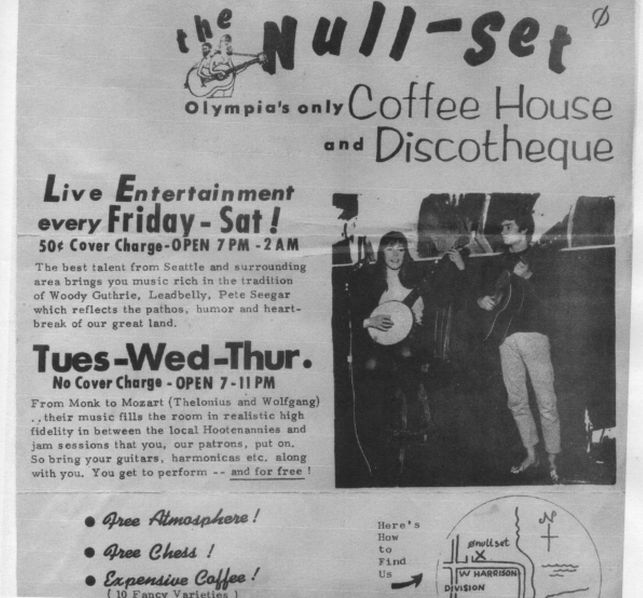

Starting our Coffeehouse: The Null Set

Bob Gillis needed a job after he resigned from teaching at North Thurston because of a flap with the administration (they had destroyed his students’ art projects). He actually thought we could make money with a coffeehouse. Pete wanted music. Bonnie Gillis just went along. But the coffeehouse was my idea. Sometime in June 1964, I invited Bob and Bonnie over for dinner and we were talking about the idea, and I came up with the name the Null Set, which everyone immediately loved. The name was in my brain because of taking a math class from Don Silberger (one of my collective household members in Seattle), who taught math at UW. I had fallen in love with the idea of set theory.

I don’t believe we thought we were being radical by starting a coffeehouse. What was radical was our politics and being hippies from Seattle. We had all lived at and attended the University of Washington . . . and coffeehouses were a big thing in the U District among students and faculty. Olympia was a small conservative town in 1964. Family life dominated. Churches were the main place people had for gathering. Saint Martin’s College was here but it had nothing like a coffeehouse. The four of us created the Null Set coffeehouse, but we couldn’t have done it without the support and backing of the Unitarian Fellowship. The members were very interested in social justice issues and artistic expression so they were happy to be helping us with this endeavor.

The Null Set also gave the Unitarian Fellowship a physical space to meet during weeknights. We specialized in coffees, Italian sodas, and ice cream for kids. I knew the owners of the Eigerwand (an early coffeehouse in Seattle) which was going out of business that summer. We got most of our dishes, Turkish coffee pots, espresso cups, and this beautiful, ornate brass cash register for good prices. It took us a few months to totally redo the building (now a frame shop on Harrison). We sanded the wood floors, put white paint on the walls. The kitchen and the bathrooms took the most work to set up. Lots of regulations to meet there. But we had friends who helped and Bob was free every day, making the most wonderful old refurbished tables with clear epoxy over his collage designs. We got the tables and chairs from St. Vincent de Paul, a huge Goodwill-type place in Seattle, and refinished them all.

The Civil Rights and Vietnam Era

Mike Murphy, a veteran and member of the Army Reserve, who had helped do the physical work of altering the Null Set space, also had been a freedom rider on the bus to Mississippi. We started a group called Thurston County Friends of the Mississippi Project. A member of the Fellowship was determined to go to Selma and join the civil rights march there, so we got a group together to support her effort. She came back and reported to us the results. The Selma March had a significant influence on the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Later, we hosted a fundraising dinner for Fannie Lou Hamer from the Mississippi Freedom Party. She brought her two kids with her, and all our kids played together, a new experience for our kids. Olympia at that time maybe had one Black family.

Again, Mike was in the vanguard, refusing to attend his Army Reserve meetings. He was put in the army brig at Fort Lewis for this protest. We gathered people to stand outside the gates at the base and protest his imprisonment and the war.

Norm Sibum was a young man writing poetry at a table in the back of the coffeehouse almost daily. He and Mike Murphy became fast friends and Mike and others (including his father who was an ex-military man) persuaded Norm to run away to Canada to avoid the draft here. He ended up staying in Canada and becoming quite a well-known poet and writer there.

In ’67 we arranged for the San Francisco Mime Troupe to bring their show, Civil Rights in a Cracker Barrel, A Modern Minstrel Show, to Olympia. It was the most exciting event for us. But the Saint Martin’s priests shut off the lights in the theater that night before the first act was even finished. The students who agreed to sponsor the show thought it was supposed to be a real old-fashioned minstrel show, which is hard to believe as this was just after the Civil Rights Act was passed a few months earlier. You’ll have to get my book The Null Set Remembered for more details on that wild night. Folks stayed for over an hour in the theater hall to discuss free speech rights.

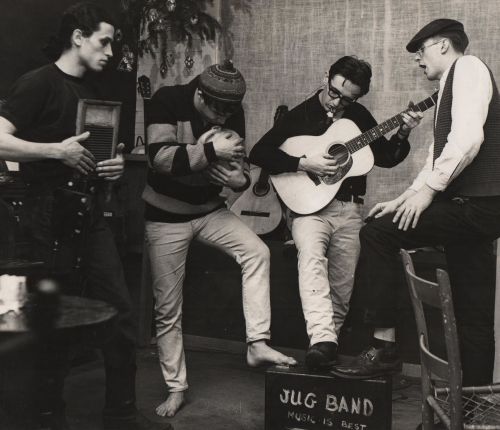

Many of the musicians coming to play at the Null Set were learning about the early jug bands of the 1920s and 30s and Lead Belly songs . . . folk music was being rediscovered and with it the history of Black lives. The music we heard spoke to the historical times of the changes that were happening all over the nation.

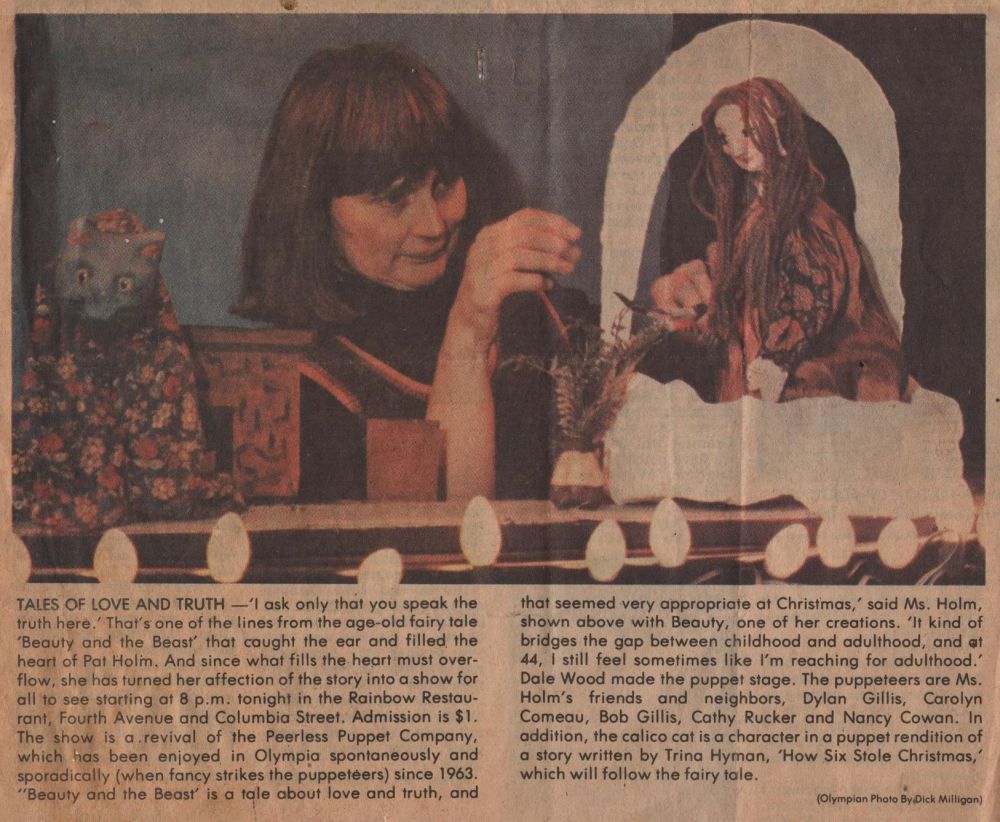

Puppet Shows

Mike, again, was our star actor in the puppet plays we performed. He was a master at improvising dialog for these fairy tales with political twists. For example, the wife, in The Fisherman and His Wife, wanted all things suburban and materialistic . . . which our hippie, beatnik traditions thought were the wrong emphasis, and Bluebeard was the monster who our young girls should avoid. Hippies loved our puppet show, Punch and Judy Meets Timothy Leary, which we took to Seattle and performed at the first Trips Festival. Read my book and find out more.

Our radical activities attracted attention. Kay Kiso, a young woman who sang at the Null Set, was from Bremerton. She had a disturbing memory of the Minutemen. The Minutemen were an extreme anti-communist, paramilitary group in the United States founded in 1961, much like the Proud Boys or other militia groups operating now. Kay told us about an incident that has never left her consciousness. Right after her son was born, she came home from the hospital to find signs in her front yard saying, “Minutemen are watching you.” It was bizarre, but not for the times we were living in, a time when the right-wing John Birchers were active in the Northwest. I remember going to our local PTA meetings and on one side of the room sat the Birchers and on the other side sat the liberals. The Minutemen had been practicing in Shelton not long before this happened on Kay’s lawn. These men had probably tracked Kay’s movements as she traveled from coffeehouse to coffeehouse spreading ideas of freedom for Blacks, free love, and an end to the Vietnam War. Bonnie Gillis and I talked about it and agreed that Kay wasn’t just being paranoid.

Barefoot John, who sang at our coffeehouse, wrote a song at that time about red-baiting: “Reds, Reds, Reds were meant to bait . . . The Birchers and the Minutemen . . . Took off in hot pursuit . . .” I know an FBI informant visited the coffeehouse now and then, to check out who was there and how much pot was being smoked (outside on the doorstep and in the basement). I think they were also checking out whether harder drugs were circulating.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer