SCHOOL

Reflections on Early Days at Evergreen and the Harbaugh Affair

By LLyn De Danaan and

Don Orr Martin

LLyn and Don were both involved in the Harbaugh Affair at Evergreen and collaborated on this story,

LLyn as a dean and Don as a student representative of the Gay Resource Center.

LLyn’s Story:

Evergreen was started as a self-conscious experiment in higher education though not a new idea. Several newly recruited administrators had worked in colleges that had experienced significant turmoil in the late 1960s, including Reed, Old Westbury, San Jose State (which had coordinated, interdisciplinary studies), and Oberlin.

Students’ demand for changes to the standard curricula of American universities and colleges and against ROTC on campus were among many issues the faculty and administrators didn’t do a very good job of addressing.

Nixon was elected president in 1968 and students were marching against the Vietnam war everywhere. In spring of 1970, four student protestors were shot and killed by the Ohio National Guard. The students were unarmed. Nine others were wounded. This compounded the angst we felt over the Vietnam war and the horror we experienced living in a nation that would kill its own children.

I was a graduate student in 1968 and in the University of Washington anthropology graduate program. While on the UW campus, the ROTC building was a target of arson, and the next year Students for Democratic Society (SDS) trashed the ROTC again. There was a bombing attempt made against the ROTC building in 1970. Black Student Union and Seattle Liberation Front occupied buildings in March of 1970 and in June of 1970. The Suzzallo Library and other buildings were damaged by a bomb. The Seattle Liberation Front was active, the most famous members known as the Seattle 7. Protests were rampant and sometimes turned violent.

Hundreds if not thousands were marching in the streets in protest of the war. I marched and I listened to speeches made by the Seattle 7, including Michael Lerner and Chip Marshall. When they went “underground,” we pondered in conversation: what would you do if one of the seven came to your door and asked to be hidden? The trial of the Seattle 7 has been written of since as an effort to suppress protest. Lerner went on to his career as a rabbi and Chip ran for Seattle City Council.

It was in this historical framework that the Washington legislature in 1967 passed legislation to found a new college in Southwest Washington. Dan Evans, a Republican, was governor. The founding faculty, 18 men, were not seemingly politically active, though some of the first year faculty, hired from 7,000 applicants, would have been in graduate school during the late ’60s and involved in some way in campus protests. I was one of them.

The college opened in 1971 with 56 full time faculty on board, 18 men from the planning faculty and 38 new hires. Nine of the 56 (16%) were people of color and eight (14%) were women. The percentage of women on faculty was about 10% below the national average at the time. Still, most of the men and administrators would not have been accustomed to working with women as equals. Even women on faculties were more often associates or assistants than full professors and they suffered discrimination by male colleagues and department chairs. In fact, notes on prospective faculty files kept in cabinets were telling and reflected male and even female prejudices against women professionals. One woman was noted by an interviewer to have a tweed jacket so tough one would be scratched standing next to her. This and some other notes were codes for Lesbian. Wives of male planning faculty were invited to read files and make notes. One of these women wrote that she saw no need to hire women faculty because the wives could fulfill all the support women students might require.

There is much more to say about these earliest times. But most important I believe is to report that many of the college faculty, especially those on the planning faculty, were advocates of “great books” curriculum and Alexander Meiklejohn’s ideals of experimental liberal arts colleges focusing on these great books and American democracy.

Some of these ideals were in place in the governance and social contract documents, as well as early programs at Evergreen: no standing task forces, equal voices in decision making, no ranks among faculty, rotation of faculty and deans, students present on task forces, consensus-style decision making.

Coordinated interdisciplinary programs became the signature offering of Evergreen. But Merv Cadwallader, who had been involved in such programs at San Jose, did not ever intend these to be the bulk of our offerings. He thought of them as alternative programs, existing alongside more conventional courses. But that’s not what happened. And there were no majors and no courses at all in the beginning. How to create transcripts that would get our graduates into graduate programs? Questions were debated in faculty meetings. Transcripts? Yes. We had to have them. Course equivalencies were born. That seemed to help. After time, when Evergreen was established, not so much a problem. We were all excited when we knew our students were accepted to very good graduate programs and even med schools.

But all of these ideals of equality and democracy went only so far. After all, this was a state institution and beholden to the state for its existence and its budget. The Board of Trustees was composed of establishment business and political figures. An early board chair had been prominent in state Republican politics. Thus, there were watchdogs, gatekeepers, and the state legislature itself was the holder of purse strings. Key staff and administrators were essentially minders of more liberal-minded faculty and students. They controlled what was seen outside the campus and, in general, the image that would be projected. Even the appearance of dogs in photographs that went out into the public was taboo because, early on, dogs in buildings and seminar rooms became a subject for outside detractors. More importantly, a nondiscrimination policy and the hiring of an openly gay man on faculty would be seen, the keepers thought, to reflect badly on the college.

We faculty were always privileged and protected by comparison with staff. That this was an egalitarian, harmonious Shangri-la of higher education was as mythical as the illusory Shangri-la of the novel. And myths abounded and still do, usually ones that suggest evil forces were always controlling or trying to control Evergreen students and faculty. The truth is more mundane. We may call it, I believe, politics.

How I came to be a dean and involved in the Harbaugh fiasco . . .

I had been a member of Evergreen’s first year faculty, one of those eight women. I had been a graduate student at University of Washington and had the status ABD, all but dissertation. Being a student there in the late 1960s was a trial. My geographic/culture area of interest was Southeast Asia. My PhD examinations were in several areas including social structure, political anthropology, religion, anthropology, and perhaps a couple of others. I had lived for two years in Southeast Asia and had assumed, when I entered the program, I would go back for dissertation field work. But Vietnam weighed heavily on us all and two of my UW professors were found to be involved in counterinsurgency research in aid of the US government while ostensibly involved in anthropological research in Thailand. Files were stolen by students at other universities that contained papers confirming that anthropologists were more than a little involved in such work. Debates at the American Anthropological Association meetings that I attended were fierce. Ultimately, AAA adopted a detailed code of ethics. David Price, anthropologist at St. Martin’s, had published well-researched books and articles on the subject of “weaponizing” anthropology.

In any case, this revelation about my professors and the war itself, led me to decide another focus . . . urban anthropology. My committee members were not so happy and administered rough written and oral exams centered on Southeast Asian anthropology My PhD examinations were in several areas including social structure, political anthropology, religion, anthropology, and perhaps a couple of others. The written exams required me to sit in a closed room with exam questions and then writing essays in response for hours. I don’t remember how many days, maybe five. Incidentally, several candidates were not passed the previous year, suspected of being high on LSD when taking written exams. My best friend was not even allowed to take the exams. She had been sexually harassed by one of the senior professors. So much shame, that even I didn’t know this until many years later.

When my all-male panel prepared to leave the oral examination room that followed the writtens, they said I had passed but they walked out without shaking my hand. No camaraderie expressed as I had observed with male students. I was not really a member of the club. Later, one committee member told me that a question he’d put on the written exams was a trick. I would have had to have read a book that had just been published to know how to respond to it.

I did lots of work in the Yakima Valley in farm labor camps during the UW years and we published a number of studies and papers that, we hoped, would improve conditions there. I did an internship in Berkeley with Christopher Alexander and applied for the Evergreen faculty.

I visited Olympia many times and each time called, hoping to get an interview. When I did, it was grand. Merv Cadwallader liked me. He said he didn’t want sociologists. He wanted anthropologists. I had an impressive resume for my age: work in urban settings with community organization, Peace Corps in Southeast Asia, great academic background, work in government in Seattle, lots of public speaking experience, and teaching. I got the job. But only after meeting and being interviewed by the planning faculty, all men. Larry Eickstaedt was standout good to me and has been a great friend forever after. One man wanted to know if I was “one of those feminists.” One man wouldn’t talk with me because he “had his anthropologist.” A man, of course.

I got the job.

I remember even getting the job sometimes brought a sting from others. David Munsell, a classmate at UW, said I got the job only because I was a woman. I’m sure others felt that way. Even a couple of first year male students said much the same.

Richard Alexander, Steve Herman, Richard Brian, Ted Gerstl, and I were given the task of forming a new program for transfer students. I was named the coordinator of the program and we did a bang-up job. We were friends and remained so after the program ended. Richard was the first person to call me an intellectual. Though I wasn’t looking for male approval, his comment made me view myself in a new way. I think I believed that the term intellectual was reserved for French writers.

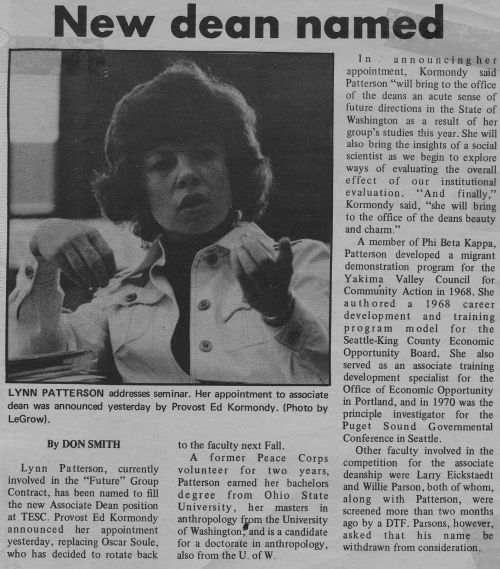

The deans’ positions were rotating. That is, people from the faculty served three-year terms, then rotated back to the faculty. We had no tenure as faculty and thus no permanent deans. The theory was that you would have to have taught at Evergreen to know how to manage it. I decided to apply for one of the openings. I was at first called an Associate Dean, but when I realized that I was doing exactly the same things that Dean Rudy Martin was doing, I asked to change my title. It was changed.

The two deans who came in with me were Willie Parson and Rudy Martin. We were one white woman, an out lesbian, relatively young; and two African-American men. This kind of leadership was unheard of in higher education. And this was a relatively new institution with a lot to get on with. We had to more than double our faculty in the next few years; we had to soothe an ever pissed-off legislature; we had to make the budgets work; we had to help build and staff academic programs; we had to write catalog copy; and we had to “put out fires” as the saying goes. The pressure was enormous. No one of us had previous administrative experience that I can recall. But we had unofficial overseers. Byron Youtz and Charlie Teske, older white men, were constantly advising and hovering. Yes, we were watched.

One thing that is lost in official accounts is the way that women supported each other. I won’t go into all of that, but when there were problems, faculty women met and gave me advice and support. Maxine Mimms, Betsy Diffendal, and I knew each other from Seattle community action days and were an unofficial team helping to get the Tacoma Campus started and supporting Mary Hillaire and the beginning of Indigenous studies at Evergreen. We got the learning resource center started and Maxine helped get weekend and lunchtime studies started for staff. Maxine and I attended a conference on credit for prior learning and came back roaring to initiate this program at Evergreen. We succeeded. Our collaboration is the subject of an oral history interview in the Evergreen archives. It is a three-way conversation between Maxine, Betsy and me.

I loved so many things about these first few years. A few of us were tricksters. We created a fake faculty candidate file. “She” was terrific and we enlisted other faculty to read her file and make comments. She could do most anything but she wanted to come to Evergreen because it was closer to Japan than other places she was considering. She taught film . . . and based her curriculum on techniques described in Zen and the Art of Archery. Students were to sleep with cameras under their pillows, for example. We tricksters sent out a fake opportunity to appear in a new ad campaign based on the then popular Dewer’s ads. Over a fake Dan Evans’s signature, we asked faculty to describe themselves by answering a few questions such as favorite book, favorite pastime, etc. We said that these profiles of faculty would be run with sophisticated photographs of them ala Dewer’s ads. We thought this was outrageously out there and no one would take the memo seriously. But some did. And enough returned the questionnaire that Evans had to issue an apology. We stayed quiet.

Mary Moorehead, an older student, wanted to start a program for returning women. She knew women in Olympia who wanted to attend the college to finish their degrees. But they were put off by the youth of students on campus and the reputation for radicalism that the college had locally. She came to Maxine Mimms and then to me, as dean, to do the footwork and get the program going. She made up a postcard invitation and sent it to at least 100 women. Unfortunately, her mockup card was made on a real post office post card with the stamp printed on one side. The Evergreen print shop printed both sides. This is a federal offense, to print a postage stamp and attempt to send mail with it. Mary innocently addressed and mailed these, believing Evergreen had some kind of permit. They were seized in the post office and federal agents arrived at Mary’s door. They threatened to seize her house and car and take her to jail. I happened to be the most senior administrator on campus when the call came from a nearly hysterical Mary in the print shop (men in black by her side). It was on me to sort it out as best I could and arrange for meetings with Mary and the feds on campus.

Eventually, the program was launched. I taught the four-credit program on top of my deanly duties. The program was called The Ajax Compact and its first cohort included fabulous and influential local women. Several women faculty took up the mantle and offered the program for a few more years. But, yes, it was a lot of pressure and a lot of work. A lot was expected of us.

Meanwhile, I was attempting to lead my life outside of the work place. It was difficult for any faculty, much less a dean, to do this. The burden was real on faculty. One could not shop for food in Olympia without being approached and asked if one would “carry a contract” for student X. We were criticized. We did not use titles and thus a phony kind of friendship was created between faculty and students. We were called at home. The opportunity for inappropriate liaisons came about naturally in this culture. Guilty. We did not rely upon lectures but did prepare and use them—always new, never dusty old notes. We read the book a week that we asked of students. We met for hour-long evaluation sessions with every student in our seminar group, usually both midterm and end of quarter. We wrote narrative evaluations, a page long, for each student. Unless, of course, you were Craig Carlson who often taped a marble and a feather to his evaluations of students. Some faculty simply were not great writers. They suffered, and evaluations were late and later. Finally, the rules changed. Well, there were rules. At some point, paychecks were withheld until evaluations had been filed. Faculty suffered through evaluation week, grumbled, the greeting to one another was often, “Are you finished yet?”

The workload was such that writers had no time to write, visual artists had no time to make art. Many were trying to finish dissertations. I had no time for research, much less writing. We laughed that in order to get a day of rest, one had to become ill. But it was true.

During the time of Rudy-Willie-LLyn, faculty were often assigned to programs. We moved faculty members like checkers on a big board . . . names on cards were placed in slots . . . to try to make each program team “diverse.” The result: people who didn’t like each other were teaching together. Gradually, over the years, people knew with whom they wanted to teach and cliques developed. Many women chose to teach with other women, and though we had nothing like departments in the beginning, later we had specialty areas, programs that were repeated, and a more regularized list of offerings. The specialty areas inevitably began to compete with one another for budget and faculty and space. Many of these changes were attempts to appeal to a potential student who needed clear pathways and promises that what one wanted to study would be available.

While I was dean, spouses of faculty came to me to complain about evaluations I had written of their partners. One woman had measured the number of inches devoted to negative comments of her husband in my evaluation. Another faculty came to lobby for his girlfriend to be hired. Stephanie Coontz’s mother, an academic herself, came to lobby for Stephanie. It was a crazy atmosphere. And over the years, it was clear that if you were related to someone on the faculty or hung around long enough, you could get a job, even though we had a rigorous process and our pick of fabulous candidates from across the country. I despised all of this.

Meanwhile, I tried to live a life. At first, I lived with my cat Portable in a cabin on East Bay Drive. I had a rough time of it and moved in with my brother and sis-in-law and niece who had a rental on Sleater-Kinney and hosted many wild dance parties. There was a lot of marijuana. It was all very silly and awkward. They were much younger than I. So I moved back into town into a big old Victorian with Ida Daum and Naomi Greenhut. This was a life you might describe as “hippie” but I thought of as merely insufferably eccentric. Ida and Naomi were both faculty members, both very bright and studious. They sat in thrift shop fur coats in front of the blazing fireplace each night preparing for the next day’s classes. They did this because they did not want to pay heating bills. Ida eventually went off to Jamaica to do field work and did not return. She died recently, a queen of Rastafari. She had been an activist friend in Seattle and I liked her very much. Naomi was a Marxist of some stripe. This was an era of the Quaalude highs and my roommate Naomi made good use of the Q. She was also a kind of bully. We all had to be home on Thursday nights for chicken soup (very good chicken soup) and were berated if late. One day, Naomi picked up a hitchhiker, Claude. He stayed. He became her lover and was assigned cook duties. One day, Ida invited an entire circus troop to stay with us overnight. They slept all around the floor in the main room (where the fireplace was). Another time I came home to find a man who had taken a vow of silence. He wrote cryptic notes when he had something to convey.

Maxine Mimms and LeRoi Smith, also faculty members, were regular visitors.

I was ready to move on and bought a house on Decatur. It was my first house and I loved it. I built a little greenhouse in the back and installed drapes and carpets.

Around about then, I met Marilyn Frasca who had been hired for the 1973 year, the year I would become dean. I also met Susan Christian who moved to Olympia with Marilyn and another friend. They lived in a pretty shabby rental that was cheap because it was due to be torn down to make way for Capital Mall. We had a great time together and I began to shop for a house in the countryside because Marilyn wanted to be out of town and I had a “back to the land” yearning.

We got the house on Oyster Bay where I still live. Susan bought the old Brenner Oyster Company building below my house. She is still there. My friend Maxine Mimms bought the house next to mine. She still owns it. Then Craig Carlson built a house on the other side of Maxine’s place. So we had our community but not a commune. Great, interesting students came and went: Cappy Thompson, now a renowned glass artist, lived among us for a while. Jeremy Bigwood, now recognized journalist and who was then working on perfecting the perfect natural high, was a friend and neighbor. I did not imbibe but did ethnographic research particularly on the use of Amanita muscaria in tandem with his work. Craig, two houses over, saw things, people crawling through the woods. Frightening. He once was angry enough to come pull up all the plants he’d given me. Joy Hardiman set up a magnificent tipi in my yard one summer.

The history of this place and these relationships would fill several volumes. Let me say that about this time Gary Snyder came to campus. I heard him and I took his thoughts seriously: getting to know everything about the place you occupy—the trees, the flowers, the people who were there before. And his thoughts about standing in the road in front of the bulldozers when they come to build a mall or strip the land. That may not be a quote but that was what I took away. So I learned about tides, I studied constellations (and eventually got a good telescope and studied deep sky objects). I learned about trees and history (and it helped that in 1991 I was called to work for the Puyallup Tribe in shellfish treaty work). Eventually, I wrote a very good book about a Coast Salish woman who lived on Oyster Bay long before I did.

We made gardens and I acquired chickens, geese, ducks, and rabbits. Everyday there were more of each, and everyday there was some death to face.

And I was a dean dealing with sexism, homophobia, budgets, legislative demands, righteous students, and faculty, and and and. I like to do things well. I thought I could do it all. But it became too much midway through 1976. I began to have vertigo spells and those turned into panic attacks. I had hypertension. I had lousy habits and my body and mind rebelled. I simply left the college and didn’t return for about a year. Fortunately, I had some sabbatical leave accrued, so I still had a salary of some kind. But it was rough and though I was taken by surprise, I really had it coming.

Now to the Harbaugh incident:

The details of the incident are reported in archived copies of the Cooper Point Journal (See November 7, 1974 Cooper Point Journal). The significant facts of the case are these:

- Chuck Harbaugh was an openly gay man from Seattle

- The faculty with whom he would serve all wanted to hire him

- Other faculty interviewed him and passed on him

- Students wanted him

- The deans, Willie Parson, Rudy Martin and I, said no. Our decision was upheld by then provost Ed Kormondy

- The deans wrote a memo that essentially said that he would not be hired because he was gay . . . and politically active as a gay man

This all seems incredible to me now. For years, I carried a memory of this. In my memory, I am sitting across a table from Don. He is angry. I am confused, dumbfounded, ashamed, maybe angry, maybe self-righteous. I don’t know. But that is a scene that doesn’t match the reported details of the incident.

I know I had seen Harbaugh speak at the Children of the Seventies events in the previous spring. I know I was not impressed. And for some reason, I believed through the years that I was responsible for the decision that denied him a place on the faculty. This was not true. But being a lesbian and being a dean, I thought and still think that I could have made a difference.

There is no doubt that this decision was not only homophobic but in violation of all the Athenian democratic ideals the college espoused regarding decision making. Faculty and students were SUPPOSED to have a say in decision making. What the deans did, with support of the provost, was contrary to all the institution “said” it was about.

What I regret, beyond being party to this debacle, is that at some point, Rudy cut me out of the process and the decision was made and the memo written without my involvement. Rudy was, he said later, trying to protect me as a lesbian. But I was out. So what really happened? And who was pulling the strings? The provost, who we knew years later was gay, supported the decision.

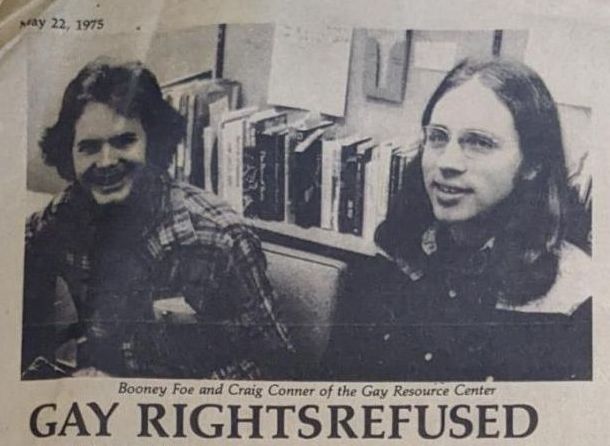

The following year, a proposal to have the college adopt a statement to support an equal opportunity document that included sexual orientation was taken to the Board of Trustees. President McCann, did not support it. The full action is reported in an archived edition of The Cooper Point Journal. (May 22, 1975 among some previous editions). Board member, Janet Tourtelotte is reported as saying that, “Evergreen is not ready for this.”

In 1974, the decision of the deans not to hire gay faculty candidate Chuck Harbaugh to fill a one-year opening, is key to seeing the cracks between ideals and reality, the cracks that have never been filled and have now and then been more crevasse than crack.

Thus, I see the Harbaugh decision as a perfect case study through which to view Evergreen’s essential contradictions.

Don’s Commentary:

I came from a small high school in rural Yakima, and though I was an honor student, I was poorly prepared for college. In 1970 I was a freshman at WSU on 4-H scholarships. I found the conservative atmosphere and huge classes at Wazoo intimidating, impersonal, and lacking in relevance for a world in upheaval. I wasn’t sure I was cut out for academic life. Then I learned about Evergreen from my dormmate who had applied to transfer there as soon as it opened. Could this be the answer for me, too? I wanted out of eastern Washington, plus Evergreen looked more my scale and it was cutting-edge in higher education.

The Vietnam War radicalized me. I got very political as a teenager in 1968, lobbying for the 18-year-old vote, campaigning for Robert Kennedy, and occasionally attending SDS meetings (yes, there was a tiny chapter of Students for a Democratic Society in Yakima). The assassinations of MLK and RFK were devastating to me. I was ready to join the growing protest movement on college campuses. Even conservative WSU was in turmoil in 1969, the year before I started there. Many students had gone on strike, the stadium was bombed, and there were big protests against Vietnam, racism, and for farmworker rights. However, by 1970 (with a few exceptions), the tone refocused on fraternities and football.

When I moved to Pullman I began associating with campus radicals, many of whom had been involved in actions the year before. Some were affiliated with the Weather Underground, a faction of the SDS, which also influenced the Seattle Liberation Front in the early 1970s. I remember following the trial of the Seattle 7, which was declared a mistrial by Judge George Boldt (of the famous Indian fishing rights decision). After many disruptions, the defendants went to jail, not for conspiracy but for contempt. Their prosecution was never successful. (In 1974, Chip Marshall, one of the Seattle 7, and I were interns at the state legislature and we worked together on a bill to promote solar-based energy sources).

I was familiar with Olympia because I had been named 4-H-er of the Year for Washington State while in high school and my various 4-H projects involved farm safety legislation, leadership conferences, and award ceremonies held in the state capital.

This new, small college in Olympia seemed like a perfect fit for me. As enrollment opened and a high percentage of out-of-state students applied, there was a push to appease the legislature and enroll more in-state youth. Though I was struggling as a university student (taking incompletes in some of my WSU classes), I applied to transfer.

I got in.

I had declared myself a feminist in 1969 while in high school. I was strongly influenced by my older sister and my mother. We had many discussions about women’s liberation and joined protests well before I moved to Olympia in 1971. In my first year at Evergreen, I eventually ended up in Willi Unsoeld’s Individual in America program and convinced my seminar to read and discuss Kate Millett, Germaine Greer, and polemics on women’s sexuality.

I had been very disappointed with my original coordinated studies program called Communications and Intelligence. I’d been training as a journalist at WSU and I wanted to continue. I was one of the founders of the student newspaper (initially called The Paper) but my faculty in communications discouraged me from this pursuit, which I found perplexing. I was also very suspicious of what was meant by “Intelligence” in the program title. Was it intelligence as in CIA? It was never explained. I was glad to be accepted into Willi’s program where I read more than a book a week.

Those first couple of years at Evergreen were chaotic and isolating for many students. Our coordinated studies programs, while innovative and challenging, kept us siloed in new ways (not by disciplines or majors but physically apart while the campus was still under construction, with few opportunities to learn what other programs were doing). We often felt unconsulted and powerless in decisions about curricula. We participated in disappearing task forces (DFTs), for example, but were not an equal voice to faculty and administration despite the school’s philosophical rhetoric. Against the wishes of the administration, we formed identity groups for support.

At the end of the first year of Evergreen in the spring of 1972, I finally came to terms with my homosexuality.

I came out to my roommates who were surprisingly blasé or perhaps didn’t want to believe it. Winter quarter 1972-73, I decided to start the Gay Resource Center, one of the first gay student organizations in Washington. By spring, with support from the Women’s Center, the GRC was hosting weekly discussion groups with people in the wider Olympia community.

The student newspaper and the Gay Resource Center (my two passionate interests) were particularly distasteful to administrators, especially to the Board of Trustees. (See my Recollections on Starting the GRC). Around the country, student-run newspapers were increasingly antiwar. Movements for women and minority rights and against American imperialism were in full swing and militant. The issue of gay rights had erupted from a riot at New York’s Stonewall Inn just a couple of years earlier. Evergreen was supposedly designed to be a place where these kinds of struggles and divisions were unnecessary. However, we were constantly threatened with the possibility that the legislature would close the school if the students went too far. But by discouraging student activism on campus, the administration fed the dialectic of conflict.

In the fall of 1972, Rudy Martin was my faculty member in the Politics, Values and Social Change program where I met several colleagues with whom I have remained lifelong friends and comrades, including Grace Cox, Susan Feiner, and Geoff Rothwell. From my interactions with Rudy in seminar the tension between us was palpable. As I recall he had come from WSU, too, and was the son of a preacher. I had tremendous respect for him, as well as for Maxine Mimms, who was one of my roommate’s faculty and with whom I had a few interesting conversations. I was anxious to prove myself an ally against racial discrimination and I sincerely worked on changing any of my behavior or language that was racist or sexist. But the distrust I felt from Rudy and Maxine left me believing they disliked gay men. It was a crushing disappointment and very stressful.

Plus, hearing all the traumatic stories of homophobia from LGBT students and members of the larger gay community at Gay Center meetings took its toll on my psyche.

I was a wreck. I felt like the administration wanted me gone from Evergreen because of my antiwar and LGBT activism. Depressed and poor (I got no financial support from my parents), I decided to look for a full-time job and take a leave of absence from school. I didn’t get credit from Rudy for my time in PVSC. Other students took over leadership of the Gay Center. I worked as a carpenter and focused on starting a collective household—the Emma Goldman Collective.

Skipping ahead a bit, in 1975 my comrades at Emma Goldman Collective, Beth Harris and Tina Nehrling, started a theatre group called Theatre of the Unemployed. Most of us at Emma’s were students at Evergreen. Beth was working as an academic peer advisor. She could feel a deep dissatisfaction growing among the student body about our lack of voice in curriculum planning. Students who wanted a particular degree had no assurance of a four-year program.

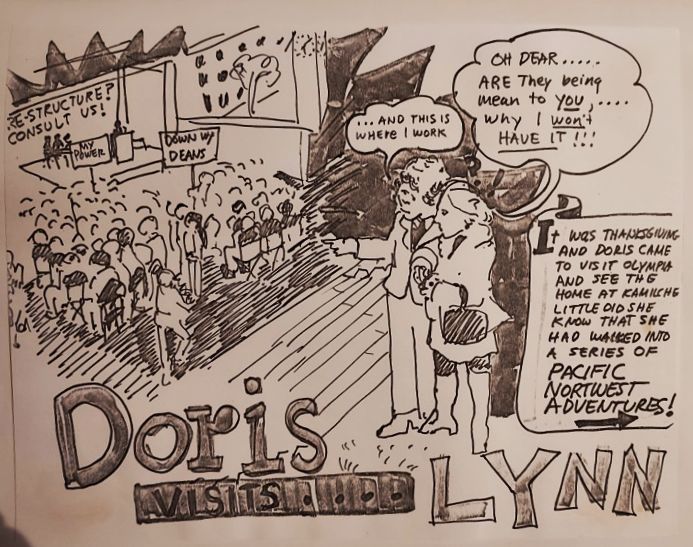

Theatre of the Unemployed decided to write a play about the convoluted planning process entitled Evergreen: Once Over Lightly. It was a spoof of the college’s ideology and of the title of their promotional catalog. It featured students playing the roles of faculty and administrators. LLyn (then dean) was one of the main characters. We performed the play (much of it ad libbed) in front of the grand stairway in the library lobby.

In response to the problems identified in the play, students rose up and shut down classes for three days.

They held a series of teach-ins and wrote up a list of demands. I learned later from LLyn that her mother Doris was visiting from out of town while all this was going on, and she was a quite shocked. Even though President Charles McCann called it all “inanity” in a campus-wide speech, several reforms were enacted that gave students some influence in planning. Theatre of the Unemployed was delighted by the response and we went on to write 15 more plays over the next seven or eight years.

While on leave in 1973, I helped to manage the struggling food co-op and I read political theory voraciously. Eventually I came back to school, taking individual contracts to record oral histories of surviving union members of the IWW and in Marxist economics.

I wrote very long evaluations.

Emma Goldman Collective moved into a 100-year-old, 4-bedroom house which we eventually bought together. We continued doing “street theatre” on controversial issues of the day, including agribusiness, corporate monopolies, racism, women’s rights, and prison reform.

Opposing Gay Rights:

Evergreen’s Early Legacy

I didn’t know Chuck Harbaugh personally, nor was I in the coordinated studies program where he served briefly as an adjunct faculty member. He passed away in 1995. I had heard of him through my cousin Sandy Fosshage who was the director of Seattle’s Sexual Minority Counseling Service. Chuck worked there as a substance abuse counselor. His expertise in this area was why he had been involved in the Evergreen program where he was popular with students and the other faculty. They recommended Chuck be hired for a one-year faculty position that had just come open. But he was not offered the job.

When a memo written by the deans came to light that they had refused to hire Harbaugh because he was gay and politically active, the Gay Resource Center staff (and much of the student body) was outraged. The leaders of the Gay Center demanded mediation. I was among the GRC staff who met to plead our case to the deans. But when it came right down to it, the deans were unwilling to change their position on the hiring. My angry words about their discrimina-tory action ended the mediation.

Neither Harbaugh nor the GRC had any legal recourse. Even though what was said in the memo was reprehensible, it was perfectly legal in 1974 for employers to refuse to hire gay people.

To me, the lofty ideals of inclusion that attracted me to the school were broken. The GRC circulated petitions to add non-discrimination language to college policy, met with President McCann and the Board of Trustees, but got absolutely nowhere. Evergreen didn’t adopt a non-discrimination policy until 1991.

There were things to like about Evergreen and many wonderful staff. The college graduated a host of highly successful students. But I believe this incident exposed a cruel prejudice, political cowardice, and a disconnect between the school’s ideals and its reality.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer