ACTIVISM

Matrix: the Rise and Fall of Olywa’s Feminist-Lesbian Magazine

By Anna Schlecht

Matrix emerged from the first lesbian community meeting in Olympia as a powerful way to build up the women’s community. And for me as one of the founders, it offered a way to build up myself by grounding my identity as a lesbian activist and writer. And in a broader sense, it helped to build up a new era of LGBTQ rights, one issue at a time.

While we didn’t realize it at the time, Matrix was the first lesbian publication launched outside the relative safety of the big city of Seattle, marking a shift toward visible communities in the small places that LGBTQ+ folks called home. This was years before local laws were in place to protect LGBTQ+ people, and Matrix reflected our lives and experiences as people living in the borderlands between rampant discrimination and equality. In that sense, we saw our lives and struggles as tied to other movements for freedom.

Everything about Matrix started small. We were a grassroots, community-based magazine, written by a handful of local women-identified people and published in a small community printshop with a circulation of less than two hundred. But we quickly realized that we were part of something much larger, and that our work to create and publish it each month followed a powerful tradition of lesbian activism via the printed word.

It would be many years later, aided by the advent of the internet and sources like Wikipedia that we learned about the evolution of lesbian publications. The first documented lesbian magazine in the US was, Vice Versa founded in 1947 in Los Angeles by Eydthe Eyde under the pen name “Lisa Ben,” an anagram of the word lesbian. Eyde’s publication produced a total of nine issues with only a couple dozen copies each that were widely shared and read. Vice Versa was followed in 1956 by The Ladder, a lesbian periodical that was launched by the Daughters of Bilitis. In 1970, a group in Washington DC founded, off our backs. In 1972, Ms. magazine brought feminist issues to the mainstream and included articles about lesbians from the beginning. Together, all of these publications helped to map out the second wave of feminism, and for us, the first visible wave of lesbian feminism.

While Matrix was primarily distributed in the Olympia area, we had some readers who lived elsewhere. We also mailed free copies to prisoners upon request. And each month we did a magazine exchange with women’s publications in many other communities. We essentially “met” our peers through this exchange, people we never actually saw in person but had passionate arguments with. These other magazines played a similar role in their respective women’s communities across the nation; they also explored national issues from a local perspective, including homophobia, sexism, classism, racism. In addition to off our backs in DC, there was Out and About in Seattle (1976 – 1986) and Big Mama Rag in Denver (1973 – 1984) among others. They all identified loosely as women’s magazines, while some more specifically as lesbian or feminist.

However, Matrix was unique in that we also tackled issues relevant within the broader left. As our tagline suggested, we examined those issues from a feminist lesbian perspective: US military interventions in Central America, Native American resistance, prison abolition, and other struggles of survival that we saw as linked to our own.

With each issue exchange, we had a palpable sense of being part of a nationwide conversation, conducted via the written word. At times it was a literal conversation—a back and forth on the definition of lesbian feminism, and other hot issues in women’s communities like Zionism.

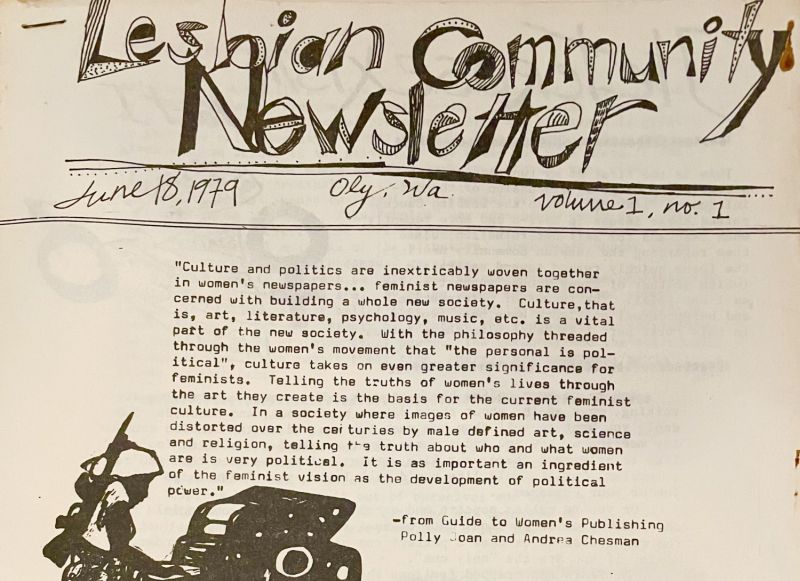

Our first issue on June 18, 1979 declared the following in our statement of purpose:

Given the make-up of the Olympia (women’s) community, this newsletter should address, confront, and reflect a diverse range of politics, lifestyles [the term, “sexual identity” had not yet been coined and we had internalized the denigrating description of ourselves as a having “lifestyles”], personal experiences, needs, and goals. As the newsletter collective, and we use the word loosely at this early stage, we have no illusions of reconciling strong political differences, or of creating homogenized versions of radical ideas in an attempt to “bring us all together in sisterhood.” Rather, we feel that the process of confronting and discussing our diverse strategies and ideologies will result in a clearer and stronger sense of direction for all of us.

Each month, we examined every layer of feminism as well as how it was connected to other political issues. We also ran pieces by women who felt they had multiple identities—as women, as bisexuals, as working-class people, as activists, and as people of color. At the time, it seemed relevant, even urgent to connect all those issues, even though our multi-issue embrace of activism seemed to rattle some readers who wanted a more exclusive focus on lesbian issues. Many years later, that perspective would be identified as intersectionality by Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, a scholar and advocate of critical race theory who clarified that many people knew their social identities overlapped and they experienced interrelated systems of oppression.

We ran Matrix as a collective, holding weekly meetings to develop concepts, identify writers, and plan for each monthly issue. While our meetings were open to any woman who wanted to attend, it’s likely there was a sense of who was welcome and who wasn’t. Years later, I heard from numerous friends who felt they had to conform or they could not fit into our rigid ideals.

One weekend each month we gathered at Hard Rain Printing Collective to produce the magazine. This involved a manual process of layout, an old school process in which the words and images were arranged on 8.5 x 11 pages and those pages were then used as camera-ready copy. The text was typed up on an IBM Selectric typewriter and cut up into columns. We gathered relevant graphics that were either created locally or “borrowed” from other publications. Then the pieces were attached to a sheet of paper by using a tool called a waxer. It heated up a small block of adhesive wax which was applied to the backside of each piece by a little roller. With the waxer, we could reposition the columns and images as needed. As a finishing touch, we went over each page to clean up the smudges with white-out and ensure things were properly aligned. It took all weekend to produce the camera-ready originals that would be left for Hard Rain Printing to print. Thinking back, it all sounds like it’s from another century, and in fact it was. Digital publishing was not even a dream at the time.

While we wrote our magazine each month, we also immersed ourselves in the writings of the lesbian luminaries of the day: Audre Lorde’s many essays, later gathered in her book, Sister Outsider (writings from 1976 – 1984); Adrienne Rich’s On Lies, Secrets and Silence (1979); This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color by Cherrie Moraga and Gloria Moraga (1981); and Charlotte Bunch’s Lesbianism and the Women’s Movement (1975). Radical women, especially radical women of color, were claiming space in the pantheon of writers of the left, and their works deeply affected us. Many issues of Matrix included quotes from these and other writers. We wanted to add our written words to this growing canon of women’s literature.

I was neither a good typist nor a graphic artist, but I sure had a lot of opinions and wrote for each issue. I was also keenly aware that most everyone else had the benefit of a college education and their writing was informed by that opportunity. But I did my best. Looking back, it’s difficult to know who wrote what because we did not include the names of any authors in the first couple issues and thereafter used either pen names or first names only. My first couple pieces were on Criticism/Self Criticism, something that was weekly practice in many women’s households, and Billboard Touring, on the practice of rewriting right-wing billboards as a tactic to thwart the religious right’s anti-abortion billboard campaign.

My last piece in our final issue of July 1984 included these excerpts:

Over time, conflicts and burn-out have taken their toll on our collective. The commonalities that banded us together also crammed our differences down each other’s throats. But I guess that’s the difference between working on an occasional social cause and really living your politics on a very personal level . . . Looking back, I think we produced an excellent magazine—one that was committed to fighting for the self-determination of all people—it affects you deeply and it ain’t always easy . . . And now it’s time to move on.

At the time of the founding of Matrix, the late 1970s seemed like modern times. However, the reality was that society was rife with sexism and homophobia. And the Olympia leftist community was not much better. Many mainstream feminists wanted nothing to do with us. We were on our own. And while we didn’t have much, having a monthly magazine helped us to see what we did have and how we could grow.

We were fortunate to have a radical print shop locally. Absent Hard Rain’s commitment to seizing the means of production, Matrix might have started as a back-to-back leaflet and then fizzled out quickly. But we thrived. From June of 1979 until our final issue released in July of 1984, we gathered the writing and graphic works of artists, activists, poets, and others. Each issue was between 10 and 20 pages. While some folks had skills, others were fast learners. And the rest came because the weekend transformed Hard Rain into a de facto women’s community center. In a sense, Matrix weekends at Hard Rain were like productive salons, devoted to robust discussions and debates of political issues while at the same time cranking out a publication.

Altogether, Matrix served as both an expression of our political ideas as well as a reflection of who we were as young people in our 20s and 30s. Sometimes it felt like the magazine was the foundation of a strong women’s community, other times it felt like an ideological scorecard of our political differences. Ultimately, the back issues of Matrix capture a series of moments during a time when women-identified people created what might now be called a ghetto, a loosely structured sub-community intended to protect and celebrate who we were.

The other woman who was there from the beginning until the end of Matrix, Grace Cox captured it well: “I don’t think I’ve ever fought harder, laughed harder, or learned more (harder?). And remember kids, when you’re out there smashing the state, keep a smile on your face and a song in your heart.”

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer