ACTIVISM

Gay Nights at the Conestoga!

By Anna Schlecht and Alexis Jetter

The following is a distillation of a long-distance exchange of memories from two women who were part of the Conestoga Task Force, a collection of friends who engaged in one of Olympia’s first gay rights actions. The commentaries below are excerpts from emails back and forth over several years that are basted together to tell the story of how a small town’s LGBTQ community reclaimed the dance floor of a short-lived disco.

Anna Schlecht: Let’s talk about the Conestoga action! Back in the spring of 1979, the owners of this new bar in town called the Conestoga Roadhouse clearly picked the wrong women to throw out of their dance bar. Some folks would have accepted the abuse and left quietly, but not you and your friends. Nope, you folks launched, “Gay Nights at the Conestoga!”

I recall that by 1979, some parts of the U.S. had learned a few things from the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion—especially in the bigger cities. It really felt like the ice age of homophobia had begun to thaw. But not so much in Olympia. With the exception of the Evergreen campus, parts of the Westside and a few businesses downtown, Olympia did not feel very welcoming for gay people. Of course, this was back when we were all “gay” and not yet known by the more inclusive acronym of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer +(LGBTQ+).

These were my dancing days, back when I had good knees. If we wanted to dance somewhere besides our kitchens, we had to seek out dance bars that were at least marginally gay-friendly, and there were a few. However, the Conestoga was not one of those gay-friendly places. It was a fancy place—a dance bar on the top floor of the Columbia building with sweeping views of Capitol Lake and Puget Sound. The owner had several restaurants in the Olympia area and was active in community affairs. It NEVER would have occurred to me to try to go there to dance.

Alexis Jetter: I remember that one night in early March 1979, together with about four women friends —who, unlike me, were straight—I decided to check out the Conestoga Roadhouse, a new bar near the statehouse that we’d heard played good dance music. The Conestoga was a watering hole for power brokers from the state legislature: politicians, lobbyists and anyone who wanted access to them, plus a smattering of lawyers, state workers and white-collar barflies. It was a quiet place, where they felt comfortable talking, drinking, bribing, and carousing.

We suspected we wouldn’t fit in, but we didn’t really give it much thought. We took an elevator to the fifth floor, which looked more like an insurance office than a discotheque. The hallway outside the restaurant was carpeted (a key detail, as it turned out) and we entered to find the dance floor pretty deserted. Most of the women at the bar wore Farah Fawcett hairdos and pumps; the men wore ill-fitting suits and ties. It was definitely not hip, or particularly inviting, and I remember feeling uncertain about staying.

But there was a large, glittering disco ball hanging from the ceiling, and a spacious dance floor. Music was playing and we started dancing together, drawing some stares, but nothing worrisome. Some people joined us on the dance floor, happy for the pulse we brought to the otherwise lifeless place. I tried out my John Travolta moves, and we did the Bump and the Pogo (jumping up and down). We looked ridiculous but didn’t care and were having a blast.

After a few minutes, though, the tone changed, and the music stopped. The owner, who was at the club that night, cut us off from the bar and ordered us to leave, telling us that we’d be arrested if we returned. We were shocked—as were several people at the bar, who looked at us with a mixture of curiosity and discomfort. We refused to budge from the dance floor and demanded an explanation. The owner said he had the right to refuse service to anyone he pleased. “If you let certain types or elements, take over a place,” he later told the Daily Olympian, “you’re going to be hurting.”

Schlecht: What a schmuck!

Jetter: Amid the commotion, the security guard, a very butch lesbian, tried to herd the five of us into the elevator. But right then one of us lost a contact lens, and we all got down on our hands and knees, searching for it on the carpet. The security guard suspected we were lying. But she waited, impatiently, until one of us announced “I found it!” and lifted it for all to see.

What must that poor woman have felt? The irony wasn’t lost on us, or on her: A dyke had kicked us out. But she had a job to do. She pressed the elevator button and glared at us until we all stepped inside. In retrospect, I think she must have been dying inside. She probably thought we were privileged college kids who were making her already lousy job even more miserable. And let’s face it: we were.

Huddled on the street, pretty dazed, we looked up to see some people filtering out of the club. As I recall, they said they thought the whole thing was ridiculous and were angry that we were kicked out.

We ended up at the Why Not Tavern, a dingy downtown bar, I wrote in my journal. “You know,” as one friend said that night, dryly, “with the rest of the losers.” We ordered beers and talked about what had just happened. We were upset but heartened by the people who’d left with us. That was actually pretty wonderful. And it encouraged us to go back a few weeks later.

But the next time, the management was waiting for us, as were some of the patrons. Some jumped onto the floor when we appeared, either to dance alongside us or to threaten to gouge our eyes out. Others threatened to beat us up in the parking lot. That just got our backs up.

We kept returning, in larger numbers each time, with gay and straight men joining our ranks, dancing with each other. One night, the manager called the police, and four armed officers ordered us to leave. Another night, in the guise of disco steps, some very pissed-off patrons “accidentally” kicked, slapped and shoved us.

As our numbers increased, the management dreamt up new ways to keep us out: imposing a dress code, a cover charge, and reducing the maximum fire code capacity—a limit that was enforced only against us.

Legally, we were on a very unsure footing. There was no protection for gay people, or anyone perceived as gay, in federal or Washington State law in 1979. A bill that would have prohibited “discrimination because of sexual orientation” in Washington State never even got a hearing at the Olympia statehouse that year. To put this in perspective: sexual relations between people of the same gender was a crime in the state until 1976—just three years earlier.

While this was going on, I was part of an anarchist collective that was writing, editing and publishing the Cooper Point Journal, the Evergreen college newspaper. So, I gleefully chronicled the whole affair, not disclosing (as I should have) that I was one of the players.

My first article, titled “Group Pickets Disco,” appeared on the paper’s front page on April 26, 1979. It was a pretty straightforward account of the dance-ins, the picketing, and the rattled, over-the-top response by the bar owner and the Olympia Police Department. But the final paragraph spoke to a larger truth:

The issue, for those involved, looms much larger than disco dancing at a downtown bar. For the women organizing the picket, the situation represents a clear case of unfair treatment at a time when discrimination usually takes a subtler tone. As the owner of a rival establishment commented: “The Conestoga handled it wrong. They made it obvious they didn’t want gays.”

Schlecht: I remember how fast the word traveled. Here it was, 10 years after Stonewall, and gay people got bounced out of a local bar. Like all good stories, the tale improved with each telling. The fact that it wasn’t actually a group of gay women, instead it was you—one gay woman, and your straight friends was irrelevant. The story was that you all were kicked out because they were gay. Maybe even worse in the eyes of the bar owners, you all were gay GREENERS!

Because you all were women, it especially rattled the women’s community. Our outrage quickly turned to action. One of your friends from the first night lived at Alexander Berkman Collective (also known as the ABC house). Soon after the ouster, you folks gathered your friends and allies at ABC to talk about what happened and what to do about it. And so, the Conestoga Task Force was born.

Jetter: Holding that first meeting at the Alexander Berkman house felt significant, to me at least. Alexander Berkmanites seemed like grown-ups. Politically sophisticated, they were older than the average Evergreen student (some had already graduated) and let’s face it: it didn’t hurt that everyone who lived there was ridiculously attractive and effortlessly charismatic. Also, the house was practically a mansion, the most beautiful of all the collective houses: a stunning blue and gray Victorian on a hill, overlooking town, with splendid cornices and dormers, ornate trim, lots of large, grand windows and a well-kept lawn and garden—the farthest thing from the shabby, crappy, falling-down hovels that most of us lived in. Going to Alexander Berkman house, as I recall, felt like being summoned to a lefty Olympus, a sun-washed palace overlooking the sound and Mount Rainier, inhabited by demi-gods.

Schlecht: A plan emerged pretty quickly—we would organize a dance-in. The idea was to mount a campaign of same-sex dancers going to the club every weekend to challenge the club’s antigay policy.

Then Hard Rain Printing Collective got busy with flyers. It was easy to find and copy the Conestoga logo onto a flyer that read, “Gay Night at the Conestoga!” As soon as they were printed, activists plastered them all over downtown. A few of the more courageous activists went down to the Yard Bird’s shopping center, then called Sea Mart, to hand out flyers to shoppers.

The antinuclear movement, active at the same time, taught us all civil disobedience as a tactic. But the Conestoga action required a little more vigorous training: disco dancing! This was especially important for those of us who were not plugged into mainstream culture (aka hippies) who had not learned this highly stylized dance form. Those who could, would then teach those who could not how to disco dance. And then there was the challenge of learning to dress like a girl. My friends all died in a pile, laughing at the outfits I found at Goodwill that made me look more like a librarian than a female disco dancer.

I remember that this started as a women’s community action, it quickly gained a broader base of support and new folks showed up at our dance-ins at the Conestoga.

Jetter: Even the local chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) jumped in, unsuccessfully attempting to meet with the bar owner or his manager to change the club’s policy.

Schlecht: Yep, we all came together. Gay and straight, men and women. People recognized that the Conestoga’s ban on lesbians was a clear-cut example of homophobia. For people who hadn’t faced discrimination based on sexual orientation, this was a real eye opener. Even on the left, there was a misperception that homophobia was a junior league oppression, more of an annoyance than the sort of bigotry that got people fired, evicted, assaulted, and worse.

I’m sure we stuck out like ants on a picnic lunch—we didn’t belong and they weren’t having it. At first, we all showed up as a pack of women, both gay and straight and headed out to the dance floor, quickly getting ejected from the bar. We often got shoved and bumped hard on the dance floor, mostly by straight men. Once the bouncer came to ask us to leave, the crowd parted like we were dangerous animals being corralled and then herded out. Even the elevator ride down was fraught, and we got jostled on our way out.

I remember that each time the bar came up with a barrier, we organizers found a way around it. First the management instituted a dress code, which forced us to scour local thrift stores to find anything that looked fancy. Then they instituted a couples-only dance floor code, so we sent out a call for men to step up and join the action.

Jetter: Finally, in desperation, they lowered the maximum fire capacity, denying entrance to several women for hours while at least 10 patrons left the bar. And the protests weren’t limited to the dance floor. On weekend nights, a group of 25 or so women and men picketed on the sidewalk in front of the club.

There was one more twist to the drama. State legislators, many of whom despised Evergreen and allegedly tried to transform the state-funded school into a police academy, were convinced that the protests were the brainchild of the campus Gay Resource Center, (which was not true.)

One local legislator, a friend of the college, was clearly ticked off when I interviewed him for the Cooper Point Journal in late May. “Every time the Evergreen budget comes up, there’s some issue that pops up at Evergreen,” he said. “And a lot of members are not that fond of the college.”

One legislator was far more irate. He was planning to hold his wedding reception at the Conestoga, and worried that the protests would ruin his celebration. According to a source, he called one of Evergreen’s top officials to complain. I never found out what he told the Evergreen administration, but the legislator held his reception at the Conestoga on May 12th, a few weeks after the protests had ended. By the time I tried to reach him, he was on his honeymoon.

Schlecht: I think you may have already moved away, but I recall the Conestoga shut down within a year or so. Thinking back, it’s hard to know the exact cause—negative word of mouth from the protests? Was it the odd location on the top floor of an office building? Or was it simply the fate of a doomed small business, many of which die in their first year? Whatever the reason, the Conestoga closed its doors, the owners took down their disco ball and the top floor was converted to state offices.

Jetter: Looking back, maybe the owner flipped out because we dashed his dream. Maybe he thought he could draw a young, stylish crowd to the Conestoga and not just the usual leisure-suited legislators and Birkenstock-clad Greeners.

It was, after all, the era of Saturday Night Fever (the movie came out in 1977, just two years earlier) and people of all ages were imitating Travolta’s Disco Inferno steps. Maybe the owner was imagining Travolta stepping onto the Conestoga dance floor in his blindingly white, three-piece stretch suit, rather than a bunch of skinny, braless hippie girls dancing with each other to the Bee Gees. Who knows? The Conestoga is long gone and so is the owner.

It started out quite innocently, really. We just wanted to have fun. So, we turned the Conestoga Roadhouse into a wild, free-for-all discotheque for one glorious night—and then all hell broke loose.

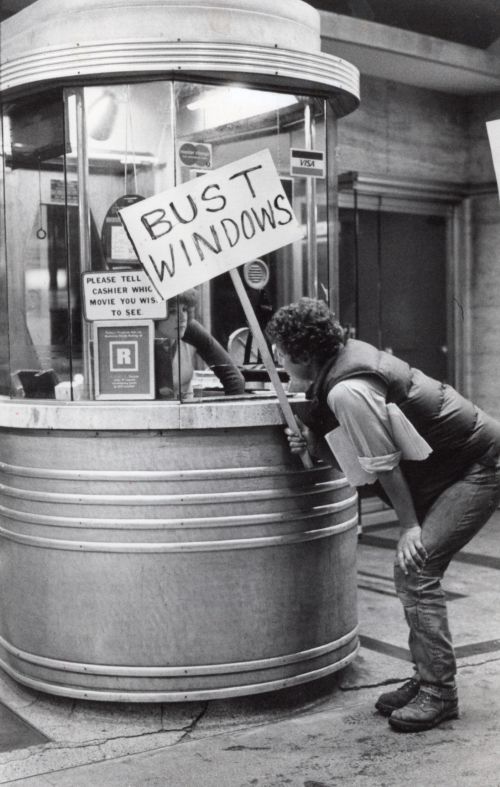

Schlecht: One year later, in 1980, many of the same Conestoga activists protested a spate of antigay films that came to Olympia. Movies like Cruising and Windows perpetrated negative stereotypes about gay men and women and fueled the homophobic backlash against our growing gay rights movement. Each time one of these films was shown, we organized pickets to discourage people from buying tickets. Both of these protests presaged the explosion of AIDS activism a few years later in the mid-1980s—AIDS mobilized the first-ever LGBTQ mass movement during which the LGBTQ community and our allies finally came out in force.

Postscript

It would be almost 15 years later before an explicitly LGBTQ+-friendly dance club called Thekla would open in 1993. In 2004, the first gay-owned, gay-advertised dance bar, Jake’s on 4th Avenue opened as an old-school gay bar centered around dancing, drag shows and alcohol. Now, most downtown Olympia bars are at least somewhat LGBTQ+-friendly. The Conestoga action was not Stonewall, but it was a turning point in our small town. In some parts of the country, that evolution never happened. Worse yet, the clock is going backward. In that context, the Conestoga protest remains a touchstone of how people can stand up for equal rights—and have fun doing it.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer