ARRIVALS

Smokin’ on the Dock of the Bay

By Joe Tougas

I remember when I was first living in Olympia. I was quite a smoker at the time—Camel filters. So I was often on the lookout for a nice place to sit and have a smoke. That day I was walking through a trashed-out industrial part of the old downtown, following the railroad tracks.

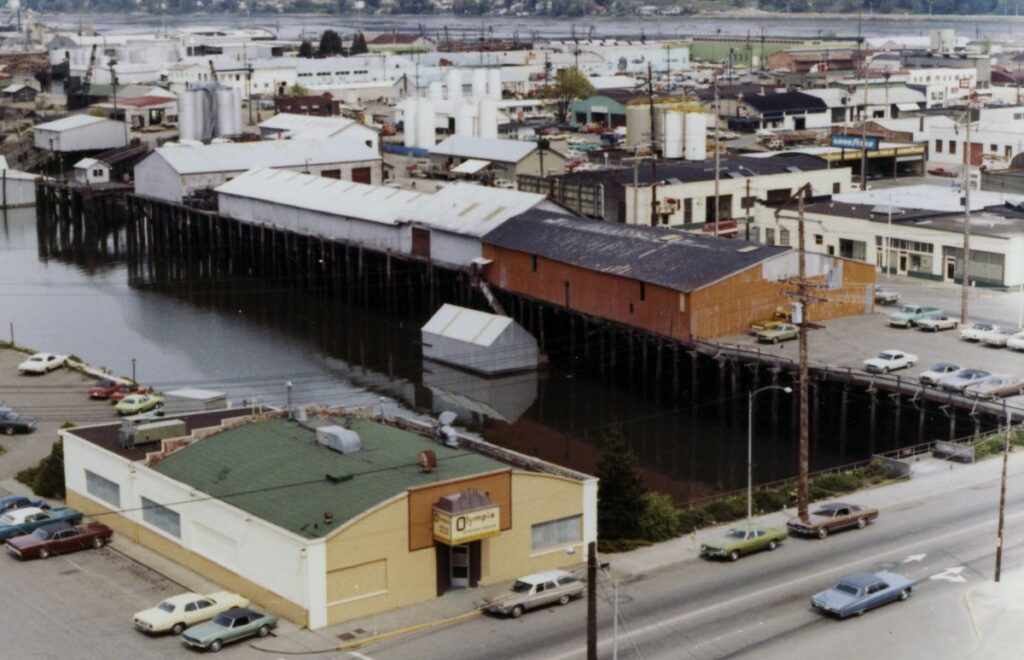

I saw a rusty fire escape going up the side of one of the rough concrete buildings. I climbed the stairs, noticing how one tread was hanging loose, up to the landing where I could sit and have a look around. I immediately saw that this was a bitchin’ spot. You could see a long way in all directions. Across the street there was a row of sheds or warehouses hanging over the water. Much of the corrugated metal siding had been ripped off, and it was obvious that most of those buildings had not been used in a long time.

I could see the water below the remnant of the boardwalk. It would be possible to walk from plank to plank and jump from one rotted-out plank to the next. But you’d have to be careful to avoid stumbling into one of the gaping holes studded with long spikes, which at one time must have held the planks together. There was a row of pilings poking up through the murky water, oozing creosote. A rainbow sheen of oil spread along the front of the pier. I could smell the diesel from three large white tanks with rust stains around their bases. I thought, what a perfect backdrop for a cover photo for a Dylan album.

As I was settling in and getting ready to light up, I saw a young woman walking toward me along the railroad tracks that ran parallel to the boardwalk. She wore a blue jean jacket and cutoff shorts, well-worn but neatly cuffed—just right for this late summer day—and a thin silver necklace. She was paying close attention to the track so as not to slip on the rusted rail.

She was quite close when she looked up and saw me sitting on my perch at the top of the metal stairs. It took a minute for her to understand what she was seeing. When she saw me, she stopped and looked down at the unlit cigarette she was holding. She smiled as she made a gesture of lighting up; I made a gesture of taking a drag on the unlit cigarette I’d been holding the whole time. I then made a gallant gesture inviting her to come up and sit beside me.

“Got a light?” we both said at exactly the same time. That got a laugh. She hesitated, looking up the rusted stairs. She stopped a couple of steps below me.

“My name’s Fran. What’s yours?”

“Charles, but I’m trying ‘Chuck’ for the time being.”

“And what ‘time being’ is it that gives you permission to just go around changing names? Are you on the edge of something big?”

I remember now that I took a breath and then said something lame like, “I really have no idea. This is just a great place to have a smoke and take in this beautiful day. Here, let me light you up and then I can show you something interesting.”

“Are you looking at that snow?” she said. There was a pile of dirty white chunks on a loading dock nearby, surrounded by a puddle.

“What snow? Oh that stuff? That must be from that place there with the sign that says Olympia Creamery. I think that’s a cold storage place where people can rent a meat locker to store their venison. It must be a popular place with the kids this time of year. They can get ice cream cones while their dads get stuff from their locker unit.”

“They must be defrosting it,” said Fran.

“Or did you mean that white stuff in the distance just peeking out above the fuel tanks? That’s real snow on the Olympic Mountains.”

“It must be beautiful up there,” she said. “Are they really a long ways away? You can barely see them.”

I said, “Most of the snow is gone by this time of year.”

“Have you been there?” Fran asked.

“Actually, I have, a few times.” I said. “My family lives in Seattle, and from there you can pretty much see the mountains whenever it’s not raining—which is, like, four or five times a year. Don’t you have much experience in the mountains?”

She said, “No, I’m more of a lakes and wetlands girl.”

“Where are you from?”

“Northern California—mostly the East Bay.”

“And what brought you to the thriving metropolis of Olympia Washington? What’s the attraction? Wait a second. Give me three guesses. Number one: you’re a logger and you’re looking for a job cutting the last of the old-growth cedar.”

“Yah, right.” She looked down at her hands and her nicely kept nails and chuckled.

“Number two: you’re a fisher person, chasing after the elusive king salmon.”

“You are way off,” she said with a little smirk.

“Number three:” I said stroking my chin, “I’ve got it this time. You’re going to college! So you, at least, are on the edge of something big. And where did you decide to go? It must be Evergreen, the place that is trying to make a home for both loggers and fishers.”

“You are sort of right on both counts,” she said. “So what makes you so smart about this stuff?”

“Well,” I said, “Evergreen’s got something to offer both the fishers and the loggers, and embraces the mountains too. I’ve learned a lot about Evergreen’s unusual classes.”

Fran said, “I know there are programs in forest ecology, marine biology, and public policy, right?”

“And where do the cigarettes come in?” I asked, waving away a puff of smoke.

“Just a habit I picked up on my summer job at Baskin Robbins. You get a smoke break every few hours. You?”

“I picked it up on my tree planting gig. Our crew leader would call a break by yelling ‘Smoke ’em if you got ’em.’ I had ’em, so I smoked ’em.”

“That must be part of your trying out something different, Mr. Charles Charlie Chuck.”

“Well, now that we have that cleared up, where did you say you are from? Did you say San Francisco? So, Fran from Frisco, that will be easy to remember.”

She made a sour face. “Please, don’t.” There was an awkward silence. “Actually, I’ve been living in Berkeley.”

After a while I said, “I’m just guessing here, but are you, by any chance, in Olympia for a new student orientation at Evergreen?” She nodded in a noncommittal way. “That would mean that you are going to the same Evergreen orientation tomorrow as me. That should be interesting. But we have a few more hours of freedom before we need to meet up with the Evergreen van, and I’m tired of sitting here waiting for this fire escape to crumble. It’s clear that we are both on the edge of something big, and a little precarious. We need to either smoke another Camel, or climb down and start our own self-guided orientation to Olympia.”

Fran said, “Won’t this just be the blind leading the blind since you are new to Olympia too?”

“Who said I was new to Olympia? I actually went to Evergreen for a couple of quarters last year. Last winter things got complicated money-wise, so I took a quarter off and did some tree planting to make ends meet. And since I’m still technically a freshman, I talked them into letting me be a guest for orientation if I would act as a kind of guide or resource for some of the new students who actually are new to all this.”

“Like me, right?”

“Yup.”

“And here we are, meeting in your palatial executive office,” she said.

“From which we can get an overview of your new home town,” I pointed out.

“So, without asking permission you just interrupted my solo excursion down the railroad tracks.”

“I’m just looking for a way to justify my existence as a Greener guide. I am offering to be your personal ‘orientator.’ Is that a deal?”

“Deal. As long as we can stop for a smoke whenever we want.”

“But before we climb down,” I said, “let’s take a close look at what we can see from here. On this very landing I see there’s a large ceramic bowl, filled to the brim with cigarette butts.” We snubbed out our cigarettes and added the butts to that pile. “And look how the door that leads into the building is propped open with a wooden wedge. We can put two and two together and conclude . . .?”

“That there are other smokers like us making use of an otherwise vacant building.”

“Bingo!”

“And who do you think would do such a thing? Probably not musicians—too detectable. But certainly artists of some sort—painters or jewelry makers? Make a note of this for later investigation.”

“Yes, teacher,” she said sarcastically. I pretended not to notice.

“See how this landing has been decorated by those birds?”

“Oh, the glaucous-winged gulls.”

“Umm, right. So you’re a birder?”

“Well, I know a few. Especially shore birds and marsh dwellers. But speaking of decorations, there’s more than just seagull droppings. Look at all these shell fragments.”

“And how do you think those shells get broken up like that and deposited all the way up here?” I asked. “ I can’t imagine the clams climbing up these stairs.”

“I give up. I have no idea.”

“Well, if you watch here for a while you will see gulls and crows picking up clams along the shore and dropping them onto hard surfaces like streets and sidewalks—and fire escapes. Then they swoop down and dine on clams on the cracked shell. And not just clams. Look at these other little shells about the size of a half dollar. Those are from the famous Olympia oyster, which is slipping away into extinction, the victim of overharvesting and pollution.”

“You’re right,” she said. “There’s a lot of cool stuff to see from right here.”

“Turning our gaze further out, up your railroad tracks, we see a big pile of sawdust next to a ramshackled building that must be a sawmill. Next to that you can see a huge rusted metal structure.”

“Wow, it must be 30 feet tall. It looks like a giant ice cream cone turned upside down,” Fran said.

“You know what that is?” I asked, putting on my best tour-guide voice. “It’s called a sawdust burner and it’s used for . . . ”

“Burning sawdust!”

“Correctamundo mon chéri. It used to be that every little logging town had one. Otherwise, they would be totally buried in that stuff. This one on the Olympia tideflats has been operating until recently, but I think it’s shut down now by new environmental standards. When I was a kid I loved it when we would be driving somewhere at night and would pass one of these fire-breathing monsters with glowing plumes of sparks and embers flying out the top. I remember considering that as a job I could do—guarding the gates of Hell and putting out any wayward sparks.”

Obviously, I was trying to impress her. She was kind enough to indulge my Mister-Know-It-All. “Let’s go down and get a closer look at this place,” I said.

I was going to give her a helping hand over the broken step, but she grabbed the handrail and pivoted acrobatically to the ground. As we rounded the corner of the sawmill an amazing vista opened up.

“They call these piles of logs a sort yard, and it is important because logs of all sizes and species go through here,” I said.

“Wow, super cool. There must be thousands of logs piled up there.”

“Millions is more like it. And these logs have been going through here for a hundred and fifty years. This is just another remnant of the timber industry, reminders that the industry is in decline but still alive. I’ve got a brother who works for Weyerhaeuser and tells me about a lot of stuff regarding the logging industry—like how there’s not enough trees to keep that industry going for more than a few more years.”

I explained that most of these logs were going to Japan, and they get loaded on ships here. We could see two ships tied up for loading. One was fully loaded and just waiting for the tide and the tugs to head out.

“See how low in the water it rides. The other one is empty, but not for long. In fact, I heard the horn blasts this morning as it was coming into the dock. You can tell a lot from the signals they call back and forth. Now they are beginning the loading process. We’re in luck. Can you hear that? That huge booming sound, like a giant bass drum in an echo chamber. That’s the sound of the first logs being dropped into the hollow of the ship. Once you’ve heard that you will always remember that sound. You see, there’s lots to be oriented to besides what we can see. There’s a lot to learn from what we can only hear. Olympia is quite a noisy place if you care to tune in patiently.”

Just then, as if on cue, I heard a familiar sound—a kind of budda-budda-budda sound. I said to Fran, “Do you know what that is?”

She replied, “Yeah, that’s a Harley making that sweet rumble.”

“Good guess, and it would make sense to someone from Northern California, but what you just heard was the sound of a logging truck coming down the hill into town. You can see the truck over there. Listen. There it goes again. Budda-budda-budda.”

“What that is, is a special kind of braking system on those trucks.”

“Listen again . . . budda-budda-budda. That’s what they call the ‘jake brake’ after some guy named Jacobson. True fact. It uses the compression of the engine to slow the truck and saves a lot of wear and tear on the regular brakes, but it makes a hell of a racket, like a dozen Harleys. Over the years a lot of towns have outlawed jake brakes, but for local people, when they hear that sound they might say ‘That’s the sound of money.’ The fact that you can still hear it in downtown Olympia is an indication of the influence of the timber industry here.”

“Now this is turning into some cool orientation. This stuff probably won’t be on the agenda tomorrow. You seem to have a special interest in sounds.”

“As a matter of fact,” I said, “I’m planning to do an independent study contract on Sonic Landscapes if I can find a faculty sponsor. One of the great things about Evergreen is Media Loan. They let you borrow high quality recording equipment which would be perfect for what I want to do.”

“Well, thank you for my first tidbits of Western Washington sonic lore,” she said. “So, can I give you a couple of things from an outsider’s point of view? First is another sound. I see from the cluster of masts over there that there’s a yacht club, and there’s a distinctive clatter that those sailboats make when the wind comes up and rattles the rigging. Hear that? Next is the smell. That is the smell of an industrial waterfront, known to us coast dwellers from all around the world. It’s a fragrant mix of salty sea air and rotting sewage. It happens anywhere that uncontrolled growth meets outdated industrial technology. I guess this is where my interest in public policy meets up with Evergreen’s scientific focus. But I just noticed something really noteworthy on the mudflats. Do you see that quite large bird perched on a log? It might be hard to see because it is totally motionless. Can’t see it? Keep looking.”

“Oh there! I see that now,” I said.

“That, my friend, is the Great Blue Heron, aka the GBH. I recognized it because of working on the Save the Blue campaign that was organized by birders and conservationists in the marsh land around the East Bay. I’ve been reading up on the birds of the Northwest, and the consensus is that the Blues are in deep trouble. I’ve seen several in California out on the delta but I didn’t expect to see one here so soon. They may all be gone in a few decades.”

I said, “I’ve lived in this area my whole life and never seen one.” Just then we heard the jake brake of a log truck just cresting the hill, and the heron, roused from its meditation by the sound, spread its majestic wings and launched into the air in a long swoop—above the tideflats, past the abandoned warehouses, over our fire escape and the log yard, landing on its perch on a Douglas fir hanging over the encroaching tide.

Fran said, “That’s one for your life list, Chuck.” Now we heard another sound, similar to the sound of a Harley but not so loud—a kind of zoom, voom vrrrrooom.

“You’ll recognize that from your favorite hot rod movie,” I said. “That’s the sound of the greasers’ souped-up cars at King’s Drive-In, the burger joint right around the corner on the main drag. The greasers hang out there all afternoon and evening in the summer, admiring each other’s paint jobs, revving up their engines, and trying to burn rubber as they take off up the Harrison hill. If you really want to see—and hear—the hot rods on parade you should come back on a Saturday night. You’ll see dozens of ‘very cherry’ cars driving around the loop through downtown, many with their mufflers modified or removed. Besides King’s there are two other burger stands—much quieter—one on each end of the loop: Eagan’s on the west end and Bob’s Big Burgers on the east end. Those two are known to be the places where the nice kids—generally the ones without cars of their own—can congregate.”

“Yeah, we passed Eagan’s and King’s on the way here from Evergreen. I’ll have to check out Big Bob’s.”

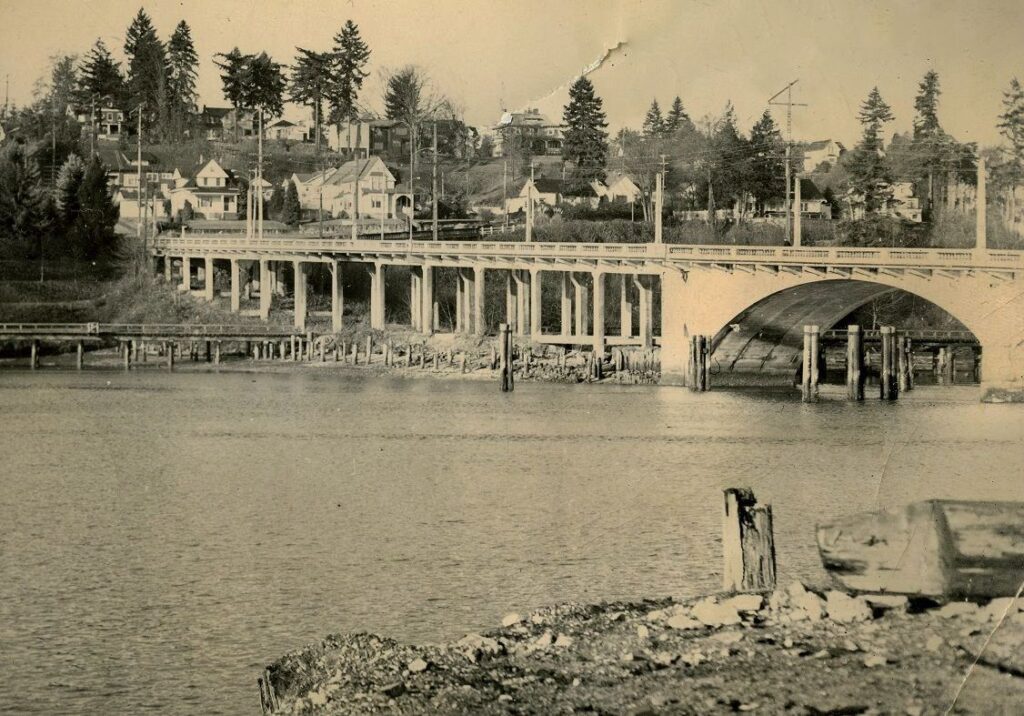

“Another Olympia sound I personally love comes from the swim beach on Capitol Lake. It’s right over there. On those same summer days when the hot rods are revving their engines, the little kids and teens and families bring out their beach towels and coolers. I love the sound of little kids screaming and splashing, and the lifeguard’s whistle. See there. There’s a bathhouse with a little concession stand where you can buy popsicles and ice cream bars. The two-tone creamsicles are my personal favorite. We could stop in there now if you want and try one.”

Fran said she would rather try the chocolate milkshake from King’s. “But maybe not today.”

“So, rain check?” I said.

“Rain check . . . or sun check.”

“Oh, I just remembered,” she said, “we are supposed to catch the Greener van to take us back to campus, right?”

“Right. At 5:00. So, I think we have time for one last cigarette. Here’s a nice bench looking out on the tideflats, and the tide is just high enough to damp down the smell.”

“And where are we supposed to catch the van, oh mister Greener guide? All I’ve got is an address on Simmons Street.”

“We’ll just need to look around. What does that sign over there say? Oh, Look, that is Simmons Street. This must be the exact spot. What luck! Wow! How did that happen?” I said in mock surprise.

Fran said, “I would chalk it up to skillful navigation by my Orientation Guide. And what’s the time?”

“By my watch it’s 4:55,” I said.

“Mine says 5:06. Damn! We may have missed it,” she said.

“I think not, my dear. See that clump of obvious Greeners heading right for us? Oh, and here comes the van. So, I guess we’re right on time. And unless I’m mistaken, we should be hearing . . . something wonderful . . . something amazing . . . something worth waiting for. Here it comes. Hear that low rumble, and how it builds to a mighty blast . . . wooooooo.”

“What is that?” she said. “It reminds me of the steamboat whistle at Disneyland.”

“Excellent guess. It is a steam whistle. It’s at the Olympia Brewery, and it blows off steam like that every day at quitting time. And that tells us it’s exactly five o’clock. So, there’s another Olympia sonic delight, marking the end of our personal orientation tour. You might notice that that low brick building across the street is the County Health Department—a handy place to know if you need a food handler’s permit for a job flipping burgers at King’s, or for an VD test.” I noticed she blushed slightly. “Well, you should be going,” I said.

“Aren’t you coming on the van?”

“No, I’ve got an invitation to dinner at a collective house called Sunny Muffin. I expect to meet some future classmates and maybe join a food conspiracy.”

“Oh, I heard about one of those in Berkeley. Sounds very cool.”

“I’m sure I’ll see you tomorrow.” I gave Fran a quick hug and sent her on her way.

“Rain check?”

“Sun check!”

NOTE: Incidents and characters in this story may be composites.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer