ARTS

A Brief History of Theatre of the Unemployed

By Don Orr Martin

Beth Harris and Tina Nehrling, their lives in limbo, set out on a road trip from Indianapolis to Olympia in late 1974. The two old friends from high school had reunited to write a dramatic new script. It was Act I, Scene I of Theatre of the Unemployed.

Beth and Tina had worked together on theatre projects in Indianapolis and appreciated the transformative power of acting out one’s story, not only for audiences but also for the creators and performers. Although they hadn’t lived in the same community for five years, their shared vision, chutzpah, and trust provided fuel for this uncertain journey. They wanted to examine relationships between women, men, and children, between grassroots communities and the collusion of corporate or governmental interests. Within a week of arriving in Olympia, Tina had filed articles of incorporation and applied for nonprofit status—Theater of the Unemployed was a reality, not just a dream.

Our troupe came together organically and by serendipity during a time of economic recession and political and cultural turmoil. We were an unusual, evolving group of mostly white, creative, working-class, young adults who wanted our perspectives to be heard. Our hard-working collective created or produced 17 plays on a shoestring from 1975 until 1981.

Beth Harris dropped out of New York University at the end of her first year. Students had shut down the university in protest against its complicity with the Vietnam war and institutionalized racism. Beth feared that a university could not prepare her to live a life of integrity. She was living in downtown Indianapolis and working at a childcare center when she decided to try college again at the just-opened Evergreen State College, which was founded by innovative educators. She came to Olympia at the end of 1971 with family friend Billy Campbell, who was also looking for a better fit to finish college. Working as a paraprofessional counselor/academic advisor at Evergreen, Beth listened to the traumas and challenges that many young women faced as they struggled to make their lives matter. She had a burning desire to help voice the commonality of their experiences and visions.

Billy Campbell (who goes by Will now but we all knew him as Billy) contemplated a career either in law or as a male model, but was more interested in getting a well-rounded liberal education in history, politics, and the arts. He had performed with Beth and Tina in children’s theatre in Indianapolis before moving to Olympia. His movie-star looks and stage authenticity gave him a stellar presence. When they got to town, Billy and Beth roomed together with some other students in a funky house in Mud Bay, and when the lot of them had to move in the spring of 1973 they joined me at the Emma Goldman Collective.

I came to Evergreen after a year at WSU also eager to escape the conservative values of my rural upbringing, looking to challenge an America at war in Vietnam and against its own citizens’ civil rights. I wanted to create new social institutions, to live and work collectively, to promote gay liberation. I got the theatre bug in kindergarten, singing solos and entertaining neighborhood moms. I reveled in dressing in costumes and taking on new personas. I played lead roles every year through high school, including being cast in a semi-professional production by the Yakima Warehouse Theatre. The opportunity to do issue-oriented, “street” theatre was a perfect fit.

Maggie Simms, like me, was an original Greener in 1971. She grew up in New Mexico, the daughter of hippies. Later, her dad was a professor in Cheney, Washington. Evergreen, the new college opening in Olympia, sounded like the ideal school for her and in her first year she studied fine arts. She was floored when her faculty member bluntly told her that she had no talent. The instructor’s husband, however, believed she was a natural actor and encouraged her to do theatre. She tried her hand at improv and was in two plays at Evergreen when she became acquainted with Billy Campbell who encouraged her to move into Emma’s in 1974. Her interest in theatre blossomed. Within a year she would take on a mammoth, full-length play with 20 actors, her first time directing.

Tina Nehrling grew up in Indianapolis and worked with Beth Harris on the high school student newspaper. Both of Tina’s parents had done theater and her dad was a radio personality for over 40 years. She appeared in her brother’s experimental films and acted in her first show at Indiana University—an unscripted improvisational play that broke the mold of traditional theater for her. She went to Woodstock, was active in the antiwar movement, and hitchhiked across the country. In 1974, waiting to do her senior year in social work, Beth called and said, “You want to start a theater?” Tina was thrilled. As she and Beth drove across the Great Plains they planned what Theater of the Unemployed could be, its purpose, principles, and focus. Beth already had an idea for a play about women’s lives.

Grace Cox transferred to TESC in 1972 after attending Highline Community College in Seattle where, as a once conservative teen, she was exposed to the radical movements of the day, such as feminism, the Panthers, and the American Indian Movement. She went on to work as a boycott organizer for the United Farm Workers in Tacoma. Grace’s family moved from Memphis when she was 11 to a bungalow directly below the flight path of the main SeaTac airport runway. Her parents were involved in community theatre and her dad even had a lead role in a Disney movie. Grace and I got to be close friends at Evergreen. I admired her wit, humor, and dedication to social change. I encouraged her to move into our collective household in 1975.

Beth, Tina, Billy, Maggie, Grace, and I, all living together in a the Emma Goldman Collective, became the core group of the Theatre of the Unemployed.

Friends and neighborhood folks also found their way into our productions and took on lead roles. Most notable was Debe Edden. Debe grew up in Pasco and Kennewick, and completed high school in Auburn where she was friends with the theater crowd but never thought theater was something she could do. She was exposed to feminism and activism at Green River Community College where she got involved in readers theater and loved it. Not long after transferring to Evergreen in 1974, she was cast in Interview – A Fugue for Eight Actors. Just a couple of months later Debe was in Ellen’s Box and remained a core member of Theatre of the Unemployed through 1980, helping to write scripts, directing, and acting in our productions. In 1981 with several notable Olympia activists such as Tom Nogler, Harry Levine, and Steven Kant, Debe started Heartsparkle Players, which focused on sexual abuse prevention. And in 1991 she was a founder of Playback Theater, which is still going strong today (2025).

Participating in the radical political and cultural upheavals of the late 1960s and early ’70s, we developed a love of collective performance as a resource for personal and institutional transformation. Our understanding of theatre was shaped by writers, directors, and actors who saw theatre as a collective cultural endeavor that provoked critical thinking and resistance to oppression. From writers like Bethold Brecht and Peter Brooks, we sought dramatic strategies to expose structures of injustice.

Each of us brought a complementary skill set to the group. Beth had the vision, clarity, and theoretical framework; Tina had passionate energy, a keen sense of justice, and a winning way of connecting with folks; Billy was a versatile actor, a worker bee, plus he had a truck; Maggie had a thirst to master acting technique, focusing on physicality and character development; Grace was a musician, singer, and eminently articulate; I was a graphic and set designer and wannabe lyricist; Debe focused on the community-oriented, humanizing aspects of this “mosaic of moving in and out of creating, performing, and working through issues.” Cate Burnstead and Greg Falxa, two close neighbors, often headed up our technical crew.

The issues we chose to examine arose from our individual interests and commitment. We employed a variety of theatrical styles, from straight drama and musical comedy to poetic multimedia readings, satire, street theatre, one-acts, and poignant vignettes. We would sit at an oversized dining table and pound out dialog on an Underwood typewriter, the person at the keyboard at any given moment having the most power. Our scripts were copied by mimeograph. We advertised auditions and rehearsed in backyards, living rooms, or rent-free spaces.

We recruited actors and tech crews from Evergreen, community organizations, state agencies, even local taverns. We did tons of research for our scripts, usually involving people directly affected by the topic. Our printed programs were small booklets of information on the issues raised in the plays.

The idea was to be available, affordable, and mobile—we would go to the people, not the other way around. We would be truth-sayers and mavericks. We performed in schools, parks, community centers, churches, prisons, grange halls, and, on rare occasions, theatres. Each play’s set was unique and easily transported. Early on, we built six sturdy plywood cubes about 18 inches square with one open face. These doubled as storage boxes, carrying crates, stage furniture, and moveable risers. We even had stage lights made from coffee cans, 2×2 poles, extension cords, and dimmer switches.

Rather than try to document every play Theatre of the Unemployed mounted, here are a few brief descriptions of our major productions:

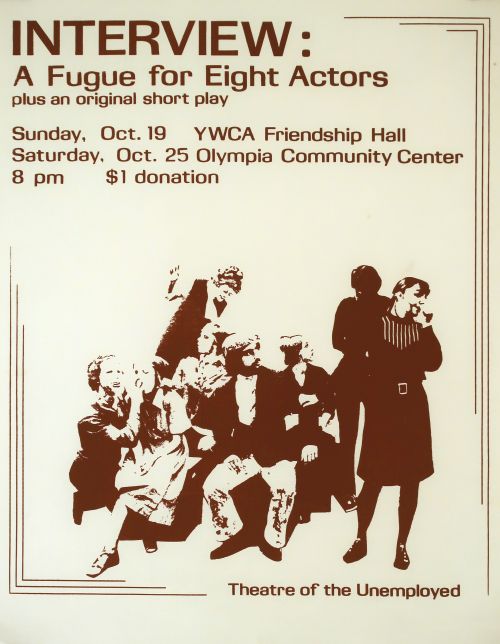

Interview—A Fugue for Eight Actors

Our first play, by avant-garde playwright Jean-Claude van Itallie, was directed by Tina as part of a conference called On Working organized by Beth at TESC. The play kicked off the conference instead of the usual keynote speaker. Four masked, smiling interviewers question applicants—a scrub woman, a house painter, a bank president, a maid. The 1960s experimental genre is unsettling. Phrases as such “I’m sorry, excuse me, next” depict social alienation, bureaucratic detachment, and emphasize the dehumanization of work. Grace directed a Workers Chorus during the conference with musical performances, readings from Studs Terkel’s oral history Working, poems, and a singalong. There were two productions of Interview, the later version went on the road. February and October 1975

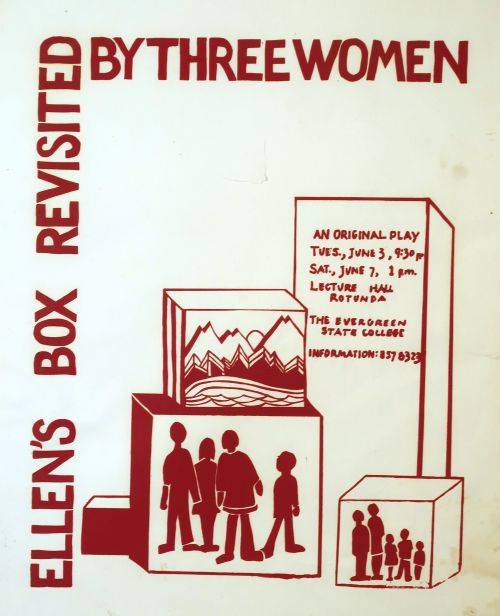

Ellen’s Box—Revisited by Three Women’s Lives

An original script was developed from improvisations by the actors—three women and a man—that focused on common themes. The improvisations drew on the actual life experiences of the women in the cast, and they instructed the male actor on how to take on roles of people who had impacted their lives. The final staging examined how the socialization of women boxed them into certain roles and behaviors and the effect this had on their identities, relationships, and boundaries. It also explored the strength and beauty of the women’s internal lives, creativity, and aspirations. Feminist issues were a core theme. The characters each created a safe place to survive—boxes—that constituted the set. The actors played multiple roles, often switching gender. Later in the year, Ellen’s Box was the first theatrical production filmed in Evergreen’s media studio. Spring 1975

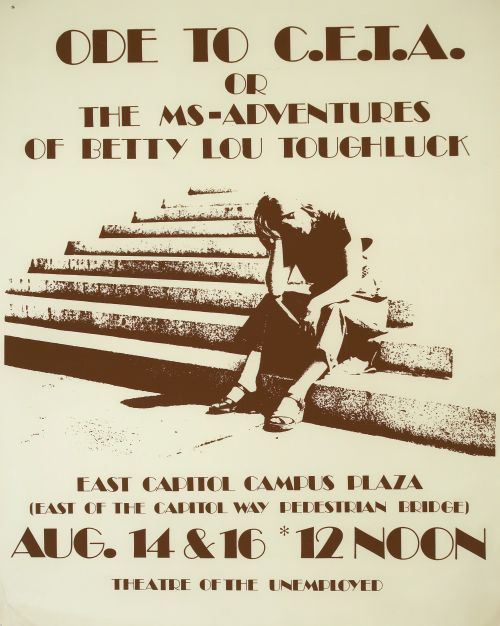

Ode to C.E.T.A. or the Ms-Adventures of Betty Lou Toughluck

An original script written with input from people hired under C.E.T.A. (Comprehensive Employment and Training Act) and some of the state employees who administered it. Betty Lou was a single mom looking for a job under President Ford’s employment program. The play was staged on a multi-level concrete fountain on the east Capitol campus in Olympia. Each level was a layer of state and federal bureaucracy. A clothesline spanned from top to bottom. Congress clipped dollar bills to the clothesline and as they descended, each layer of government cut off a portion so that little was left for the workers at ground level. A live band of accordion, clarinet, tuba, and trombone played We’re in the Money. The lunchtime audience of state workers sat on terraces across from the stage. This play received national publicity via Associated Press wire service. Summer 1975

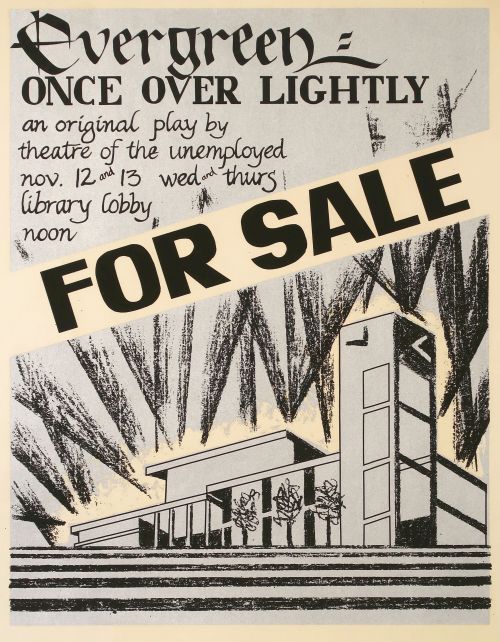

Evergreen Once Over Lightly

A spoof on the contradictions between The Evergreen State College’s idealized educational rhetoric and its reality as a state institution. Beth Harris had spent a year as an academic advisor listening to student dissatisfaction and complaints. These experiences and our research about Evergreen’s curriculum development became the basis of the improvisational script. The play focused on the lack of student voice in curriculum planning. College faculty and administrators were caricatured in sketch-comedy style. We exposed and lampooned the arbitrariness and uncertainty of Evergreen’s curriculum planning process. The 1970s were the height of America’s youth rebellion, and when students realized how they were viewed and treated, they gathered en masse, shut down the school for three days, conducted teach-ins, and wrote up demands. Curriculum planning changed. It was the most dramatic audience reaction Theatre of the Unemployed ever got. Fall 1975

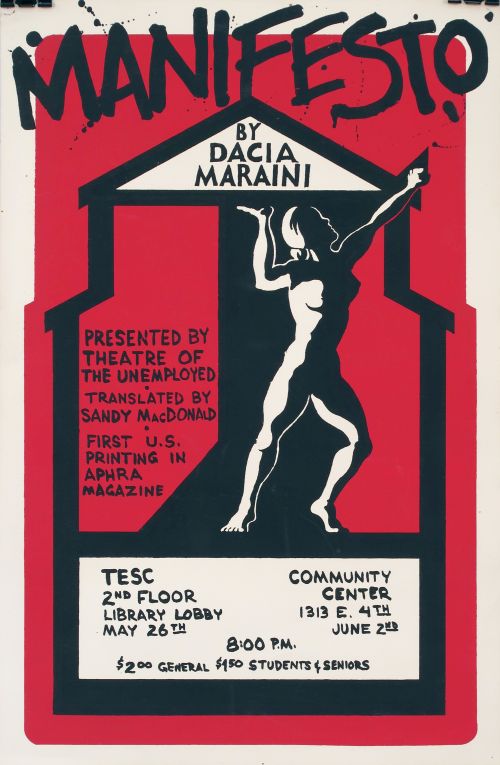

Manifesto

A three-act play with 37 characters written in 1972 by Dacia Maraini, an Italian feminist. It follows the life of a young woman in her quest for identity and independence in a social order where men control, objectify, and abuse her. After her arrest and imprisonment, she develops an 11-point manifesto on women’s rights and humanity. Maggie Simms received college credit for directing the play, rehearsed over seven weeks. She cast 20 actors, mostly Evergreen students, who were anxious to be part of a drama production because the college still had no formal theatre department. Maggie employed a rehearsal technique of acting out the intention of each scene without using the lines in the script, which helped with blocking and gave the actors insight to their characters. Tina Nehrling played the epic lead role. The set was designed by a batik artist. Performed at Evergreen. 1976

That’s Agribiz

An original work and perhaps Theatre of the Unemployed’s most intersectional play, That’s Agribiz blended issues of industrial agriculture, fundamentalist religion, nuclear power, water rights, farmworker conditions, processed foods, organic farming, and consumer education. The fictional U & Me Sugar Inc., a Mormon-owned mega corporation, applies political pressure to build nuclear power plants so they have enough electricity to pump millions of gallons of water from the Columbia River to grow sugar beets on arid land. Meanwhile they suppress farmworker organizers and market highly-processed foods, putting their sugar in nearly everything, as a middle-class family tries to eat a healthy diet and make ends meet. A guitar-playing narrator introduced each scene with Woody Guthrie songs. An ingenious set design featured three rotating panels in a mobile frame showing: the corporate boardroom’s idealized “farm of the future;” a humble farmworker clinic; and a supermarket shopping aisle. We wrote new lyrics to That’s Entertainment (That’s Agribusiness), and Food, Glorious Food (Food, Overpriced Food). Performed at the Olympia Community Center; for a Tilth alternative agriculture conference; and at venues in eastern Washington and Oregon. 1976 and 1977

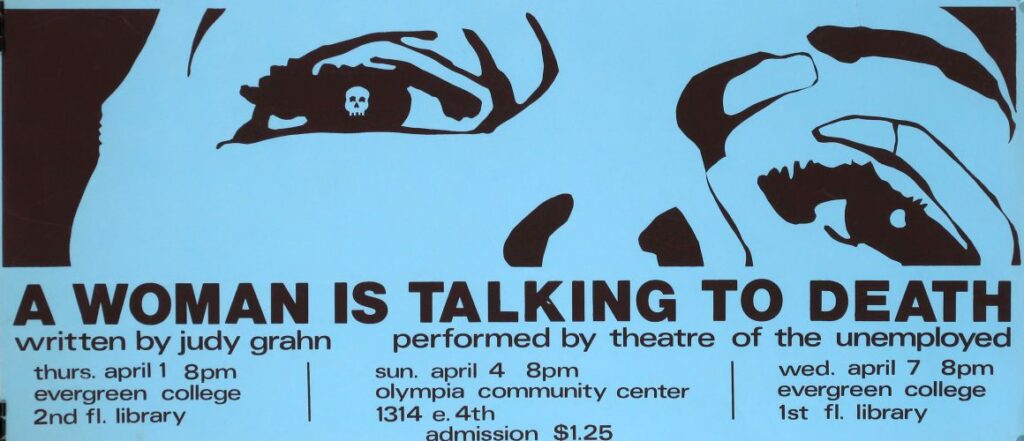

A Woman Is Talking to Death

Lesbian writer Judy Grahn’s poem with nine “scenes” was transformed into a multimedia performance piece with narration and stylized choreography. It is a complex and deeply emotional story that starts with a gruesome traffic accident on the Bay Bridge, and the legal and psychological consequences for the Black driver and lesbian witnesses. It examines guilt, suspicion, racial and sexual social status, violence, and death, ho death. We performed it in Olympia and at Langston Hughes Cultural Center and the Asian Cultural Center in Seattle, where they insisted we not use the “n word” as written in the poem. 1976

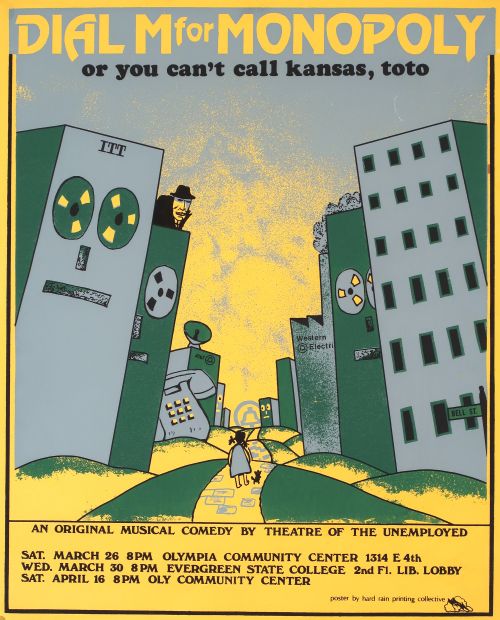

Dial M for Monopoly, or you can’t call kansas, toto

It’s hard to visualize it in our age of cell phones and the internet, but in 1977 there was only one telephone option, Ma Bell (we changed it to Pa Bell). Dial M was a musical critique of monopoly corporations, in the style of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, sung to the tunes of The Wizard of Oz. Dorothy, another a single mom looking for work (Somewhere I’ll Find Employment), becomes a lowly directory assistance operator. During a whirlwind of training, she accidentally uncovers corruption and unfair labor practices. She decides to “Go off to the commission, Commission of Utilities” to testify against corporate greed. Along the way she meets a fired lineman stranded on a telephone pole, the elderly Emma Rustin who depends on her phone but can’t afford it, and a cowardly union boss. Phone company employees helped us research the issues. The set was a giant push-button phone with elevator doors and an upper platform where Dorothy is held captive by the Wicked Wiretapper until she is rescued by her friends. Performed in many locations in 1977. We can’t take sole credit but, shortly after our play, the Bell monopoly was broken up.

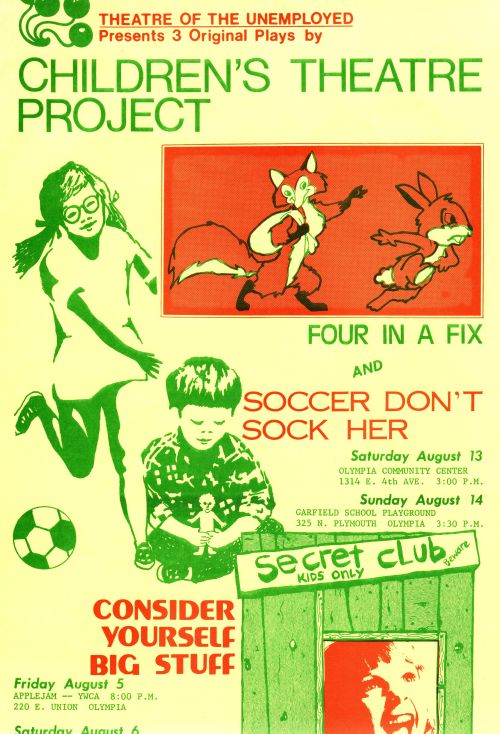

Consider Yourself Big Stuff, Four in a Fix, and Soccer Don’t Sock Her

The Children’s Theatre Project was a nine-week program involving eight actors, ages nine to 16. They did over 20 performances in three towns of an original children’s play focused on divorce called Consider Yourself Big Stuff. After being turned down for grant funding, Beth paid Debe and Tina to coordinate and direct the program. A local newspaper reporter came to interview the directors, but the young actors demanded to answer the reporter’s questions. “Everything in life is not Disneyland. It doesn’t hurt to face the bad things and find out how to deal with them,” one of them said. The young actors also helped write two other short plays, Soccer, Don’t Sock Her and Four in a Fix. These dealt with problems kids face: body image, disabilities, parents, poverty, sexism, and bullying. Where else would kids find an art form dramatizing their problems in a positive way, performed by kids? Summer 1977

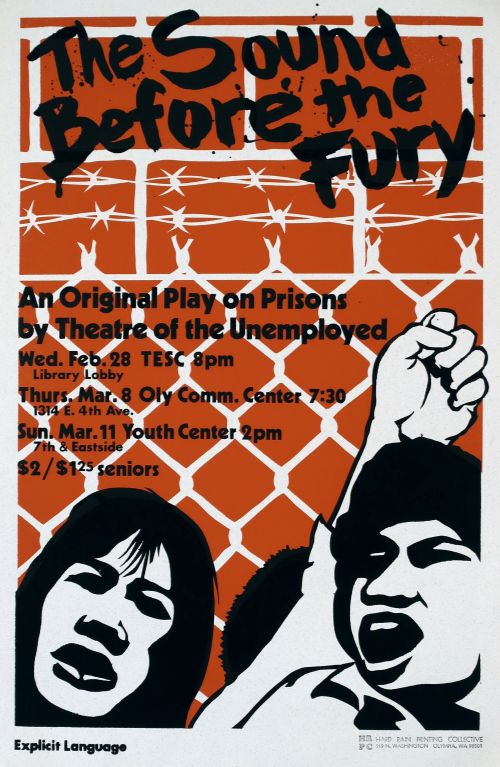

The Sound Before the Fury

Through the 1970s, Theatre of the Unemployed visited people who were incarcerated in all of the state’s adult correctional facilities for both men and women. In Walla Walla Penitentiary “reform” measures allowed prisoners to establish clubs. We supported a group called Men Against Sexism (MAS), a club that protected young, weak, and gay men and trans women from sexual assault. We did performances, workshops, and asked those incarcerated to help us research and write scenes about resistance to the racist, dehumanizing, and dangerous conditions in prisons. The result was a series of vignettes about prison life as well as the effects of incarceration on families and supporters. At an officially sanctioned banquet we attended on July 4th weekend 1978, prison authorities in Walla Walla feared a disturbance. They put several members of MAS in isolation and detained members of our group in the city jail. No charges were ever filed against us, but MAS was disbanded and some of its members were sent to other prisons. During production of the play, members of our multiracial cast, especially those who had close relatives in prison, experienced trauma from the issues raised and the stress of the show. It was our last major production. Performed in Olympia, Seattle, and Portland. 1979

It is interesting to note that all the core members of Theatre of the Unemployed were deeply affected by their work in theatre and continued a lifelong commitment to performance arts, especially in service of social change. Beth used theatrical techniques as a college professor, and to organize protests against US foreign policy and apartheid in Palestine. She noted that direct action was less work and more immediate than script writing. Tina taught drama in middle schools and continued to adapt scripts she developed in the 1970s on topics such as date rape. Maggie and her husband produce original, historical dinner theatre in Colorado and she writes strong, complex female characters into these shows. Will performed plays in San Francisco for several years after leaving Olympia. As a member of Citizens Band—formed in the 1980s—Grace performed and recorded original songs and labor tunes until being sidelined by a stroke in 2023. I acted in or directed community theatre in Olympia well into the 1990s and continue to write plays and do readings of my stories as part of a queer elders writing group in Vancouver, BC. Debe continues to do Playback Theater performances in Olympia and around the world.

This story is based on interviews I conducted in 2020 and in collaboration with Beth Harris and Tina Nehrling. I hope to someday edit the interviews into a podcast with snippets of dialog and songs from our shows.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer

I enjoyed reading this article. Thanks..

Oh my gosh – brings back so many memories! I was only on the periphery, in the audience for a few of the performances, and continue to be amazed by the brave, passionate, prescient people you all were and are. Don, thank you for documenting this history!

How cool is this?