ACTIVISM

The Unstoppable Unitarian Women of the 1980s

By LLyn De Danaan

The late 1970s and early ’80s were heady times for lesbian and radical feminism. Locally, 1977 was the year of a chaotic Washington State Women’s Conference that brought together 4,200 women in the heat of July Ellensburg. The conference became a battlefield not only over ERA but also lesbian rights and a plethora of other issues. Christians, Mormons, radical feminists, and lesbians hammered away at their differences.

Coincidentally, Dixy Lee Ray was the nonconformist, pro-nuclear-power and bring-on-the-oil-tankers governor of Washington 1977 to 1981. She wore sweatpants and men’s shirts and brought her dogs to public events. If not for her politics, we would have loved her.

I, meanwhile, stoked myself with bell hooks Ain’t I a Woman (1981) and Margin to Center (1984), Adrienne Rich’s Lies Secrets and Silence (1979), Marilyn Frye’s The Politics of Reality (1983), Barbara Deming, and Lizzie Borden’s Film Born in Flames (1983). I all but memorized Monique Wittig’s work, particularly The Straight Mind (1989). I read Audre Lorde and Mary Daly. Betty Friedan and other straight feminists called us the “lavender menace.” We were.

All of this reading gave me a perspective that has informed my life. I had and have an “angle of approach” (Monique Wittig) that guides me.

However, I was a single lesbian parent and lived in the woods. My social life revolved around The Evergreen State College. And Ricco, my son, and I were relatively isolated on Oyster Bay. I wanted a connection with a broader community and believed that Ricco would benefit by knowing people outside of my rarified world of politics and teaching.

I joined the Olympia Unitarian Church in the mid-1980s and I found my local heroes.

I didn’t know much about Unitarians other than having read Ralph Waldo Emerson and being a devotee of May Sarton. After I joined, I learned that there had been many famous Unitarians . . . many of them activists in the abolition movement, social services, women’s movement . . . and politics in general.

When I joined, the Olympia congregation was meeting in a small meeting house built in 1872 but acquired by the small Unitarian group in 1958. It looked very much the proper New England-style church: a small, white structure with a proper steeple. There was no permanent minister, so congregation members took turns officiating at Sunday services. It was a non-patriarchal flattened social structure. It seemed very kid-centered and I found the members warm and welcoming. I stayed with the Unitarians through many changes and valued my years of singing with the choir.

My tribute here, however, is not to the church itself but to the several women whom I might never have had the opportunity to meet if not for the church. Carol Fuller, the first woman superior court judge in Thurston County, Jocelyn Dohm, founder of Sherwood Press, and Meta Heller, a former D.C. lobbyist, tax reform and antinuclear activist, were members. Meta, probably in one of her gold lame blouses, climbed the fence at Bangor during one action. She called it “the best day of my life.” These were among those whom I admired. They were outspoken, farsighted, community-minded, and determined to work for justice.

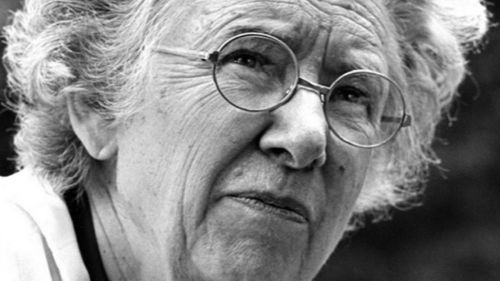

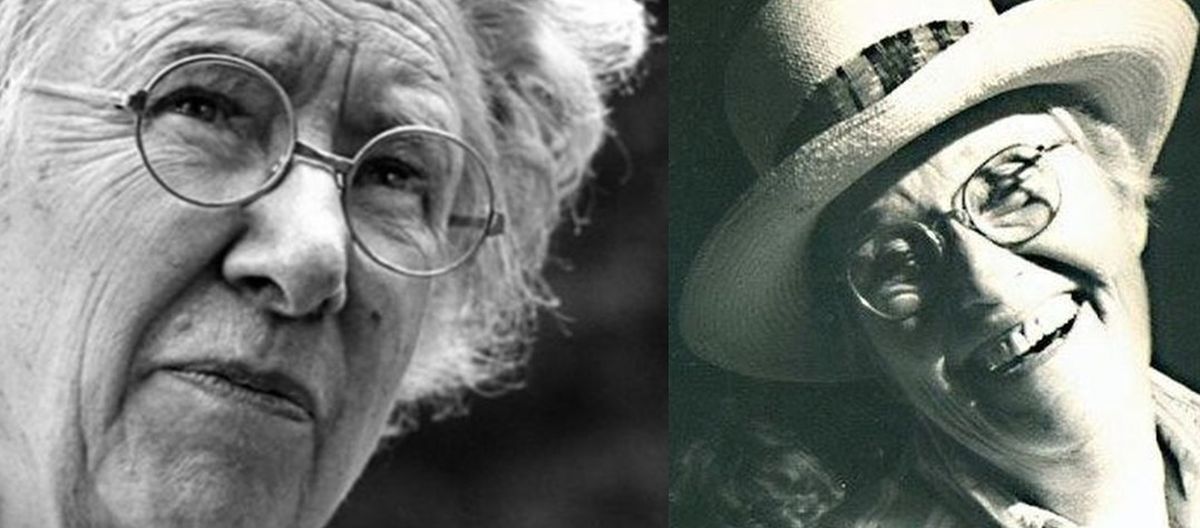

Two I want to especially remember are Gladys Burns and Kay Engel.

Gladys Burns was exceptional. I knew her daughter, Carol, a documentary filmmaker whose film about Frank’s Landing and the fishing wars (As Long as the Rivers Run) remains a magnificent tribute to those times. Then I met Gladys. Gladys was the executive director of United Good Neighbor (now United Way), president of the Washington State Mental Health Association, and she kickstarted or organized many of the social services in Thurston County. Her work for a mental health center began in the 1940s. When I first knew her, she was in her mid-70s. A friend told me that Gladys and activist women friends, including Mary Lux, a Washington State legislator and Olympia City Council member, met on Sundays to plot their next steps to make Olympia a better place to live. A Unitarian friend, Carol McKinley, and I were so impressed by Gladys that we considered making “What Would Gladys Do” bracelets to rub like Aladdin’s lamp as we contemplated our actions in difficult community situations.

Kay’s hearty, non-gender-conforming way of being in the world always cheered me. She was gregarious and good-humored. She was forever ready for action and prepared to be on the front lines of it. Kay and I cofounded the Unitarian Triangles group for gay and lesbian members before the church became a Welcoming Congregation. In the early 1980s, when Zan Lussier was founding of Stonewall Youth, Kay was a big supporter. Later, she helped to establish the church’s Out of the Woods shelter for homeless people. She was called St. Kay by cofounders.

The thing that most inspired me about Kay in the 1980s was her involvement in the White Train protest movement and the Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action. The White Train was used to transport nuclear weapons from Texas to the Naval Submarine Base at Bangor on the Kitsap Peninsula. The protest was nationwide but Bangor is in our “backyard” and the train passed over local tracks. Kay was there, one of the blockading dissenters. Kay introduced me to Hollis Giammatteo who spoke at the Unitarian Church. In 1984, Hollis and seven other women walked the tracks of the White Train from Bangor to Amarillo to “form a chain of resistance in towns and cities along the tracks.” They were sparked by peace communities everywhere and determined to carry a message of nonviolence. Kay and Hollis were my teachers, instrumental in forming my dedication to pacifism and nonviolence.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer

Gladys Burns was a mentor and a dear friend to me. She, Mary Moran and Margie Reeves supported me and many other parents and children in our community. She taught me to be an organizer for support systems for parents. She said all parents need to ask for help and she encouraged me to do so. I attended Parents Anonymous meetings that she organized where I learned many helpful parenting skills and was able to talk about my struggles and joys. Gladys, Mary and Margie were activists as well as open, loving souls. I will never forget their impact on my young self and on our community.