ACTIVISM

Recollections on the Founding of the Gay Resource Center

By Don Orr Martin

This story uses fictionalized names.

The first phone call I took (that wasn’t a crank call) was from a lesbian in Lacey. It was 1973 and I was the founder and sole staff person answering the phone at the Gay Resource Center, a new student group at Evergreen. She and her partner had both been divorced from men, and between them they had five kids living in a double wide trailer. She wanted to know if I could offer them any help regarding child custody issues. They were terrified their ex-husbands, who were soldiers stationed at Fort Lewis, would come after them. They invited me over to talk. I learned they had held their “wedding” the previous year at a gay-friendly bar in Tacoma. This was forty years before same-sex marriage was legalized in Washington state. I had no idea what to tell them, so I just listened. Not long after this call, I was flooded with phone messages from people wanting help and support. I needed to compile a list of gay resources fast.

But let’s back up a bit. I was a farm boy from Yakima who had already fallen hopelessly in love with other boys by the time I went off to college in 1970. All unrequited. James was different. In the fall of 1971, James and I were among the first class at a new experimental college, The Evergreen State College in Olympia. He was from a rich Republican family in Portland. Handsome, athletic, and rebellious. He had dropped out of high school and traveled around the world. I, on the other hand, was the product of an under-funded, rural school system and though I was in the top ten percent of my class, I was poorly prepared for higher education. I had not done well in my first year at Washington State University. Both James and I hoped enrolling in this innovative college might allow us a chance at academic success. We were from different social classes but our personalities somehow instantly bonded. We both loved the scenic beauty of the Pacific Northwest and the area’s radical history. Unlike most men I knew, James talked about his feelings. It was easy to share my fears and dreams with him. He somehow made me want to learn and explore new things. He coaxed me to hike wilderness beaches and climb to mountain lookouts. I was falling madly in love again.

When I came out to James, I was terrified of losing his companionship, but I was also dying to explore a deeper intimacy. I decided it was worth the risk, so I screwed up my courage, found a safe moment, and haltingly told him I was gay. He didn’t even flinch. He asked me to describe same-sex desire. I, of course, hoped he had some inkling of these feelings too, but looking back it was a big clue that he didn’t. Rather than distancing himself, however, he seemed to get closer. We took long bike rides together. We stayed up late talking about the coming socialist revolution and how we could be part of it. We even napped together on his bed, drowsy after trying to stay on top of our hefty reading assignments.

There were four of us roommates in the just-built dorms. We had a common kitchen/living room and our own bedrooms. I did most of our cooking. The others eventually figured out I was gay but, amazingly, tolerated living with me. We got along well, though we all hated dorm life. Our building was cold concrete and smelled of new construction. The campus was isolated, still being built, and muddy. James convinced the four of us to find a house to rent in town.

It was a nineteenth century Victorian, four bedrooms in relatively good condition, though the porch was sagging, the kitchen needed work, and there was standing water in the dirt cellar. The house had been empty for a while. We convinced the landlord to let us put new linoleum on the kitchen floor and spruce the place up a bit in exchange for a reduction in the rent. We painted and wallpapered downstairs before we moved in. The next day, we came back to discover that all the way around the kitchen the wheat-pasted wallpaper was eaten off the walls about eight inches above the floor. Rats. Inspecting the kitchen closely for the first time, we found a series of holes gnawed through the backs of the cabinets and a maze of tunnels in the walls leading to the cellar. We boarded up the holes, set traps, and got things furnished and rodent-free just in time for James’s parents to visit.

I was a budding chef and proposed to make a simple yet hearty dinner for this gathering. I desperately wanted to impress James’s mom. To my dismay, however, she seemed to take an immediate disliking to me. “How on earth did you learn to bone a chicken,” she sneered. James’s dad snickered. That was when I realized James must have told her I was gay. It was clear she didn’t want me anywhere near her beautiful boy. About a week later, James packed up and announced that his parents had found him a job with a movie crew filming in the Himalayas. It was an amazing opportunity. And it was the last time I ever saw him.

When I realized he wasn’t coming back I was devastated. I spiraled into a deep depression, began drinking heavily and blowing off classes.

Keep in mind this was only two years after the Stonewall rebellion. It was still illegal for men to have sex with each other even in liberal Washington state. Gay liberation was beginning to emerge in big cities but was nonexistent in tiny Olympia. There was no support, no bar, no organizations, no role models. At some point I was sober enough to realize that if I kept falling in love with straight men, my life would be miserable. James after James. Heartache after heartache. It took me a while, but I eventually figured out if I was going to lead a gay life, I would have to befriend other openly gay men. I could move to a big city, but I’d always been a country boy at heart and that didn’t appeal to me much. The other alternative was to help build a gay community here in Olympia.

At that very moment students at my new college were starting to form student-run organizations. There was Ujamma for Black students, MEChA for Latino students, the Asian/Pacific Islander Coalition, the Native Student Alliance, the Evergreen Political Information Center (EPIC), the Women’s Center. They all got office space, phones, and a small budget. Here was a chance to start a gay and lesbian student group. I don’t know where I found the gumption, but in late 1972 I petitioned the college to establish the Gay Resource Center. The GRC would be one of the first officially sanctioned college organizations for gay students in Washington. There were already gay organizations at the two largest universities, but I believe neither was funded by the institution. It took a lot of persistence to get college funding for the GRC.

The administration initially put up fierce resistance. The nascent college was being closely watched by the state legislature. Conservative politicians looked for any excuse to cut funding. A publicly gay organization sent shivers of fiscal fear through many in the administration. At first, they decided the GRC could not have an office or a phone—there were suddenly no more available. My pleas to be treated equally to the other student groups were summarily dismissed. Fortunately, Maryanne, who staffed the Women’s Center and was a lesbian, offered to let the GRC share their tiny office and two-line phone.

Right away I started a weekly discussion group. Back then we called it a “rap” group. At Maryanne’s suggestion, I borrowed our format from the feminist movement’s consciousness raising meetings that were appealing to a broad spectrum of women around the U.S.

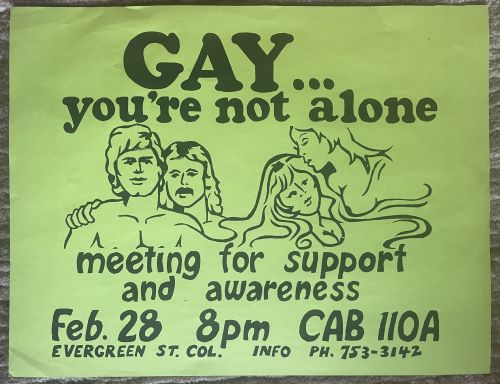

The only regular means of communicating on campus at that time was a newsletter put out each week by the college public relations office. The GRC was not allowed to announce its presence or its meetings in the newsletter. So, I silk-screened posters and put them up around campus. A small group of brave souls met in one of the large carpeted junctions between hallways in the bowels of the library building. Determined to challenge the PR director’s blackout policy, I organized some straight supporters from other student groups to stage a sit-in at his office. We demanded publication of GRC meeting announcements or we would put our posters up in the state legislature. He relented.

We wanted the GRC to serve the whole community, not just the college, but we were nervous about advertising in town because of potential threats. The college was a somewhat safer haven away from downtown and it got enough regular visitors from the community that slowly the word spread about our meetings. Eventually as many as twenty people from the surrounding area were attending our rap sessions, mostly men, including some older guys who in the 1960s had been involved in the Dorian Society, a pre-Stonewall gay rights group in Seattle. The rap sessions were mostly a social affair, but we discussed a wide range of topics from the personal to the political. One of the school’s early adjunct faculty checked us out, and he sometimes hosted a movie night at his house.

As the Gay Resource Center became more visible, the crank calls, death threats, and desperate messages for help started pouring in on the phone line. Gay-curious students would slowly walk past the open office I shared with the Women’s Center or they would linger in the hallway, desperately wanting to talk. I was not prepared to deal with this drama alone. Maryanne, studying for a degree in social work, was a tremendous support. She talked me through a lot of stuff. I eventually convinced Jerry, another student who was coming to the rap sessions, to help me figure out what we could realistically offer as a “resource center” for people with no rights. Jerry had a wider circle of friends and professional contacts. I visited the other gay university student groups in Seattle, Pullman, and Bellingham to understand what they were doing.

We presented our case to the campus governance board for why the GRC was needed and should be funded. We provided excerpts and data from phone calls, attendance numbers at the rap groups, and the list of services people were seeking, such as mental health and substance abuse counseling, legal aid, and medical advocacy. After a close vote of the board, we got our own office and phone. When women joined the staff, we changed the name to the Lesbian and Gay Resource Center—over the years the name would change many times as new sexual minorities were added, eventually becoming the Evergreen Queer Alliance.

The year 1974 was pivotal. A whole new group of activist students was running the office. I had taken a leave of absence from school for financial reasons and for my own sanity. When you go from organizing protests demanding change to actually running the day-to-day operations of the thing you said you wanted, you realize it’s a different skill set. I needed to step down, at least for a while.

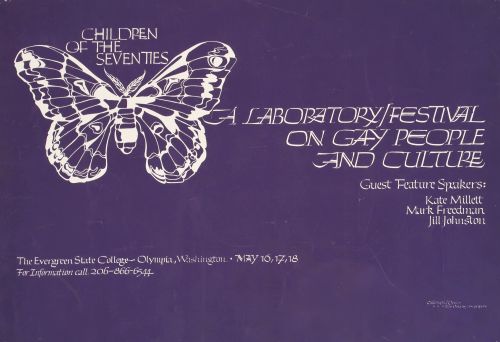

That spring, the new GRC staff hosted perhaps the biggest LGBT event ever produced in Washington state at that point. It was called Children of the Seventies: A Laboratory/Festival on Gay People and Culture. Featured speakers included Kate Millett, Jill Johnston, Mark Freedman, and Arthur Evans. Three days of workshops, music, and art. Hundreds attended. An array of exotic characters invaded Olympia and the GRC scrambled to find housing and accommodations. It was an amazing event. There was broad support on campus, except from the college Board of Trustees.

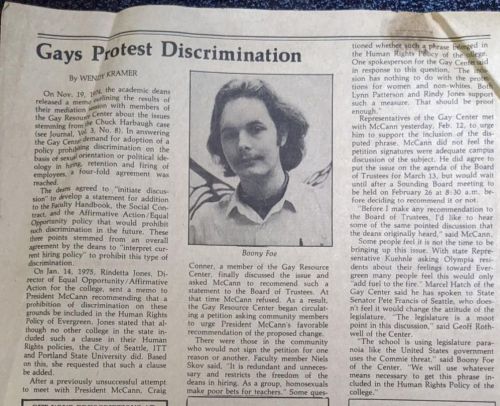

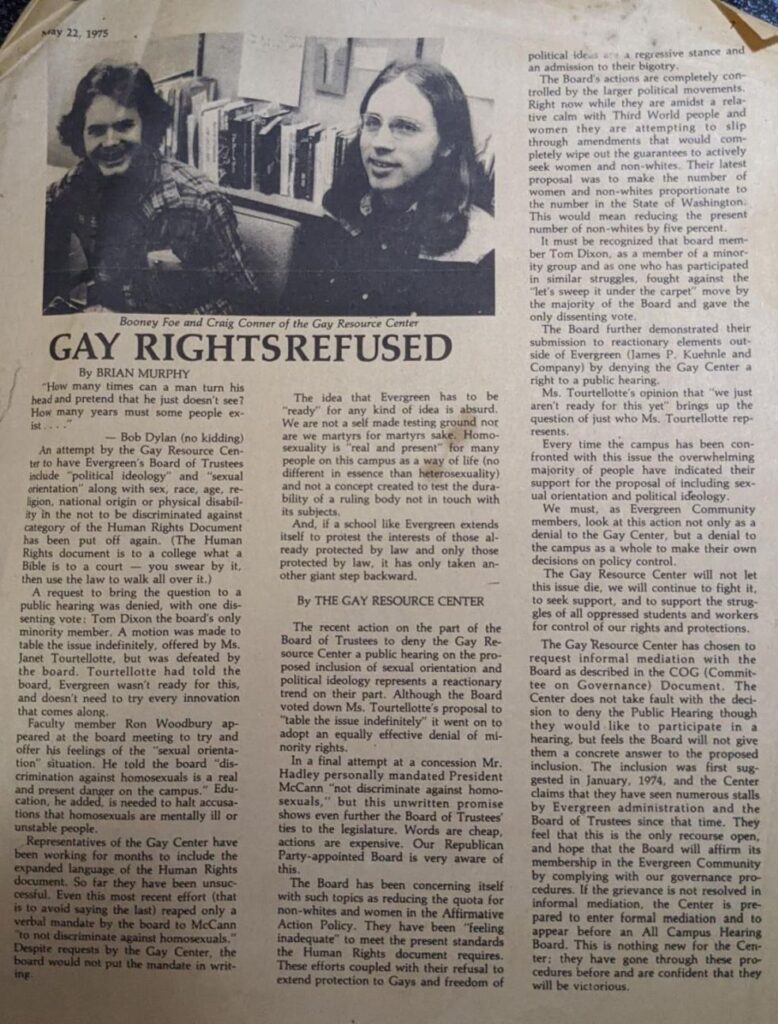

Later that year, one of the coordinated studies programs hired a highly regarded substance abuse counselor from Seattle as an adjunct faculty. Chuck Harbaugh was well known in the gay community in Seattle. He became very popular with the students at Evergreen and was recommended by his colleagues for a permanent position. But the deans rejected his application and wrote a blatantly discriminatory memo that was leaked to the press. They put in writing that they refused to hire Harbaugh because he was gay. This led to ongoing protests on campus and eventual arbitration.

The GRC had built strong support from other student groups by the time classes started in the fall. I came back in time to sit across the negotiating table from deans Lynn Patterson and Rudy Martin, a white feminist and an African-American. I remember feeling betrayed and losing my temper at their casual denial of our human rights, at which point Rudy halted the meeting. Ironically, at least two of the school’s deans were gay and were so intimidated by the institutional power structure that they felt they couldn’t speak up. There was no such thing as employment protection for LGBT people in 1974, and so in the end Chuck Harbaugh had no basis for an appeal. Homophobia won that day.

The GRC staff persisted for years in trying to get the college to adopt a non-discrimination policy on sexual orientation. The Board of Trustees simply refused to consider it. They said the public was not ready; that even though the college was innovative, they didn’t have to be innovative about everything. The first recorded non-discrimination policy I could find for Evergreen was 1995, well after the governor had banned discrimination in state employment by executive order.

Looking back 50 years, I think about all the students who cut their teeth on the struggle for LGBT rights at Evergreen and who went on to be champions of social change. I believe the Gay Resource Center and similar organizations played an important role in advancing human rights and liberty in our society.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer