FOOD

Olympia F.O.O.D. Co-op from the Floor Up

By Beth Hartmann

The first day I volunteered at the Co-op was the day we laid the linoleum at the downtown store. There were several people there, and it was hard to know where expertise was coming from, if there was any. I did my part, carefully placing tiles where the glue had been spread.

I was volunteering at the brand-new storefront Co-op in the spring of 1977 because it sounded like a lot of fun and a way to get involved in something exciting in my new and happening community.

I had come to Oly from Seattle the summer before to go to Evergreen. After growing up in Los Angeles, I had spent five years in Seattle selling my crafts and trying my hand at a number of things including the apple harvest in eastern Washington. From what I was hearing, Evergreen was paying people to go to school, and it had all the appeal to me that it had to the many independent-minded hippie leftists who came across it. I had a little over a year’s worth of credits to complete to get a degree. But I had disappointing experiences with visiting faculty and was looking for other ways to get connected and active without further delay.

Greg Reinemer and Charlie Lutz had secured the downtown location on Columbia Street. They did many things to lay the foundations of what is now the Olympia Food Co-op, most of which I don’t know. My memory tells me that at least one of them did this work for Evergreen credit, an “individual contract.” As with so many memories of the time, this one is incomplete and not first hand.

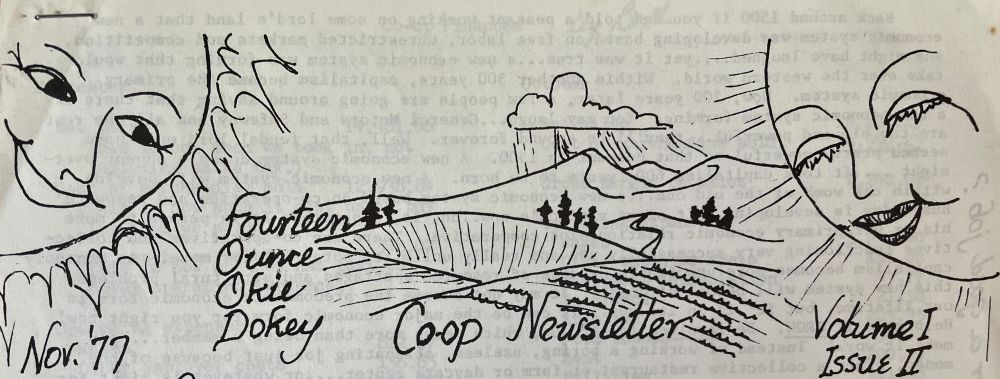

Charlie and Greg had set up the legal name of the Co-op as the Fourteen Ounce Okie Dokey (F.O.O.D.) Co-op. And it was as such that it opened in the spring of 1977.

At the Columbia Street storefront, the floor in place, I watched coolers for produce and dairy arrive. They must have been purchased at auction as we did later with an expanding store or to replace makeshift shelving. There were beautiful wooden bins for bulk grains and nuts, custom built by some loving member of the community.

Then came deliveries. fifty-pound sacks of flours and rice from Cooperating Community Grains in Seattle, fifty-five-gallon barrels of honey and oil, milk and yogurt and tofu from the Seattle Workers’ Brigade. It was fun to cut down forty-pound blocks of jack and cheddar cheese for sale. There were volunteers on hand to stock the first produce. I’ve learned over the years that every food co-op has the same aroma made up from all those natural foods. Our Co-op now had that scent and was suddenly ready to open.

The Co-op was set up from the get-go as a consumer-owned cooperative. As such, there needed to be a meeting of the members to make important decisions. So it was that a decision was made to hire some staff for a salary of $200 per month. Charlie was hired first. Anna Schlecht had a lot of community support at the meeting and was hired second.

It turned out that Charlie had had enough after the long months of getting this enterprise off the ground. I was lucky enough to be picked to take his place that summer. While he worked out his last weeks, I went on a hitchhiking trip all over the Southwest, my last great adventure before settling into my new job.

The Co-op was busy from the start. We worked our asses off taking deliveries, stocking food, working the antique cash register. I saw a lot of joy as people welcomed this new busy storefront. We signed up new members, many of whom wanted to be more involved. Members could work in the store for a discount, so we kept track of that on cards in a file. I taught working members how to break down those blocks of cheese in just the right sizes while others stocked shelves and trimmed produce.

Money came in and money went out. The problem was that none of us knew what all might be involved in keeping good records or managing the money—the members’ money—responsibly.

Not long after I joined the staff, Jim Cunningham was also hired. He didn’t know bookkeeping but he knew we needed some. We always wanted to build connections with the Senior Center across the street, so we put up a card on their bulletin board asking for a bookkeeper. Before long we had an applicant named Sandy Sanderson. He thought we were whacky as could be, but was glad for the work.

Being something of a math nerd, I was very interested in understanding this aspect of the organization. I spent a lot of time with Sandy and Jim, and we developed better ways of keeping track of what was coming in and going out, what we owed and what was owed to us. It wasn’t long before we had an accurate and understandable picture of where we stood with regards to the members’ money.

We had been keeping the store afloat with the sales just fine. But we had been living in blissful ignorance of the demands of the government that we pay taxes. All kinds of taxes. It turned out that this was not optional, not negotiable, and an existential threat to the Co-op. If it could not survive as a business, it would not survive. And we weren’t far off from the feds literally coming and locking our doors.

There are heroes who came to rescue at this point, people with financial expertise who helped us break down the specifics. The Co-op was doing good sales. As things were going, we were in a good position to stay in business if we could find a way to pay those taxes and keep moving forward. I understood the numbers.

We put out the word to our members. We were able to show that the Co-op could make it as a business if we were able to get past this obstacle. As has so often been the case in Olympia, community members stepped forward and extended generous loans. Taxes were paid. The little storefront downtown grew up and moved to the west side of town in 1979. Years later, a second and bigger store was opened on the east side. A million stories later, the Olympia Food Co-op continues to thrive.

We encourage readers to use the form below to make comments and suggestions. Disclaimer