ACTIVISM

Violence and Non-Violence: A Tale of Two Tactics

By Anna Schlecht

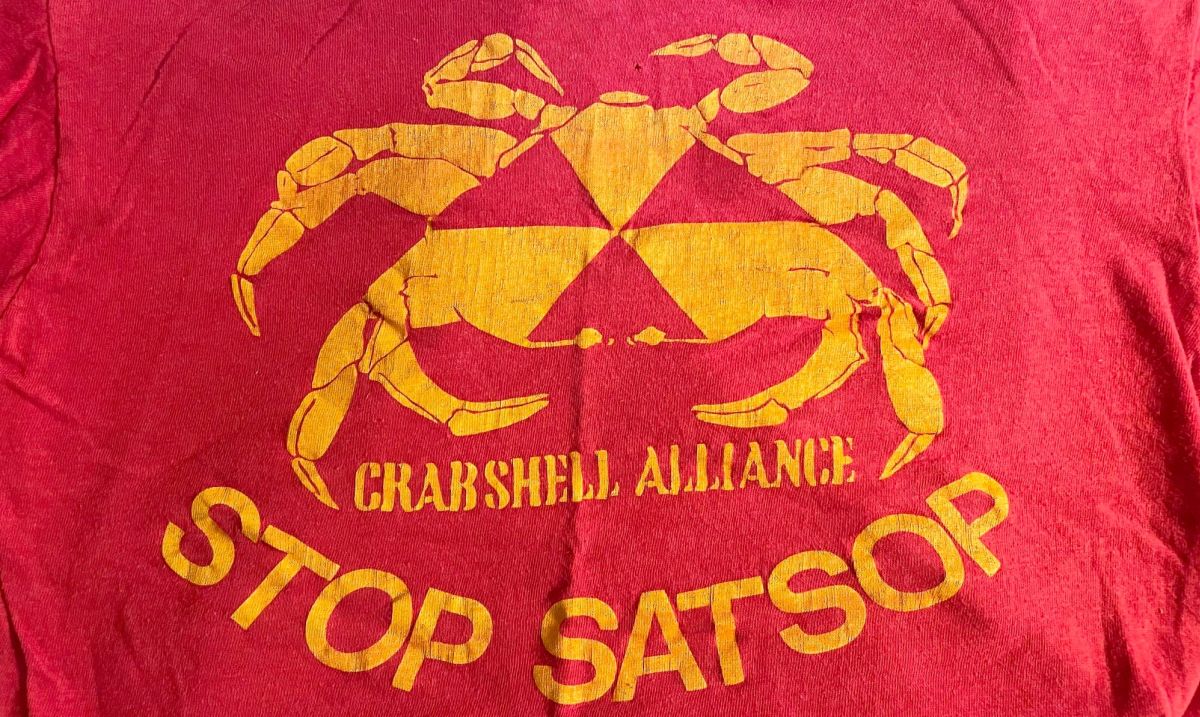

Crabshell Alliance was a vastly different kind of political action group for me. Until 1975, my political experience had involved bouncing around the antiwar movement in Madison, Wisconsin, most of which was DIY, male-dominated, and raucous. In Crabshell Alliance, I found myself as part of a well-organized effort with clear strategies, effective tactics, and women in leadership.

As a young activist, I saw the anti-Vietnam War movement propelled by a wide range of tactics. One of my idols, Abbie Hoffman, was a serious activist as well as a talented political jester who recognized the immense value of using humor and theater to inspire war resistance. Hoffman wrote an activist manual titled Steal This Book, which explained how to “Survive! Fight! And Liberate! In the prison that is AMERIKA.” This book was everything to us young radicals, and I definitely stole my copy.

The manual I really needed would have been a safety guide on how to avoid the sexual predators rampant in the antiwar movement. Young women, especially teenage activists like me, were easy prey for older men. This is not to say that leftist men were unique—the same abuse almost certainly happened among young Republicans, but you wouldn’t know because right-wing women didn’t talk about sex, much less sexual abuse. In those days, there was a complete lack of political analysis of rape and domestic violence. Women’s liberation was different than fighting imperialism, but no less crucial. Those experiences of dodging all the sexist vultures drove many women like me into the women’s movement.

Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Madison was a hotbed of antiwar action. I was join in high school student walkouts and often went downtown for rallies that turned into riots once the police arrived with clubs and tear gas. I always wore a coat with big pockets to carry bandanas, along with baking soda and water to mix up the tear gas antidote.

While I was still in high school, the ROTC was bombed so often that the recruiters resorted to having a plain storefront without a sign. My most vivid memory was the August 1970 bombing of the University of Wisconsin’s Sterling Hall in Madison. Like many, I was stunned by the scope of destruction and the death of a late-night researcher, Robert Fassnacht, caught in the blast. A few years later, one of the bombers, David Fine, held legal defense team meetings in the back room of the Main Course Restaurant, my hippie collective. Talk of the bombing rumbled across the political landscape with activists all over Madison immersed in an impassioned debate of tactics—do we fight violence with violence, or should we flip the script and respond with nonviolence?

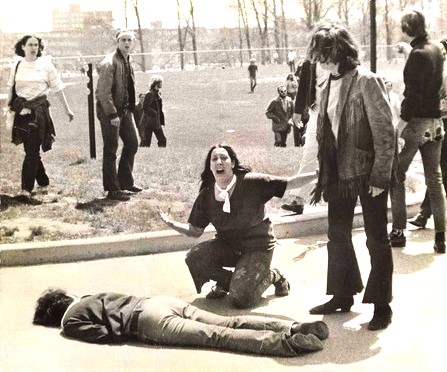

The Sterling Hall bombing was inspired in part by the Kent State and Jackson State shootings, which had occurred a few months earlier. State police in both incidents fired on students, killing four at Kent State and two at Jackson State. I was deeply affected by the searing image of a horrified teenager kneeling over the body of a murdered Kent State student. This girl, Mary Ann Veccio, was my age and could have been me. While the Vietnam War was raging on the other side of the globe, it seemed that we were on the verge of a civil war here.

For White kids my age, this was the first experience with violent political repression. Some of the older White activists I knew had been part of the civil rights movement and had gone south as allies for Black activists who constantly faced threats, assaults, and murder. For me, this was a more distant reality. As many journalists pointed out, Kent State was the first time that middle-class White kids got gassed, clubbed, and even murdered.

Nixon had left the White House in disgrace in 1974; the Vietnam War ended the following year. The Wisconsin campus that once pulsed with antiwar fervor had devolved into an apolitical party scene. The UW Library Mall, which had been the battle zone of protestors versus riot cops, was now filled with fraternities hosting huge outdoor costume parties. I felt deeply disillusioned and wanted no part of college life.

The worldview of my generation had shifted. There was no longer a sense that revolution was imminent; instead, many of us began to look for ways to create smaller revolutionary communities. Thousands of us flocked to the West Coast looking for a fresh start. Around this same time, the anti-nuclear movement created a hugely different approach to political organizing.

The No-Nukes movement had emerged as one of the big issues following Vietnam. In 1973, President Nixon had rolled out a plan called Project Independence to make the US energy self-sufficient by 1980 through conservation programs and conversion to “alternative” energy sources. These new sources were going to be nuclear power plants, with a goal of building 1,000 by the year 2000. While the idea of energy conservation was a huge hit with environmentalists, the nascent nuclear power industry seemed to be driven by corporate profits more than conservation, much less public safety. The potential for nuclear disaster was a real and present danger.

In Washington state, opposition to nuclear power was organized by the Crabshell Alliance. Crabshell was one of several alliances using aquatic names, including the Clamshell Alliance in the Northeast and the Abalone Alliance in Southern California. While separated by thousands of miles, there was a call-and-response dialogue between organizers that harmonized our approaches. This kind of collaboration—sending copies of regional pamphlets and posters across the country by mail—gave me a deeper understanding of the movement I was a part of.

The Olympia Food Co-op, where I worked, was one of the recruitment hubs for the Crabshell Alliance. The organizers were seeking people from the greater Olympia area to join the movement to stop a nuclear power plant under construction at Satsop, 27 miles from Olympia. At first glance, Crabshell and the entire antinuclear movement fit the model of leftist activism—getting the largest number of people to go to a protest and raise hell. But differences emerged quickly.

First, we all had to take nonviolence training. I attended a class taught by Ada Keith (Kramer) who in turn had learned about the power of such activism by working with Glen Anderson of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, in addition to other organizations. Ada gave us an overview and lead us through a series of scenarios to practice and deepen our understanding of non-violence as a tactic for social change.

Many non-violence movements were inspired by the Highlander Folk School, a training center in Tennessee for social justice activists and leaders. I knew about the Highlander School because one of the teachers at my free school (aka alternative high school) was Thorsten Horton, the son of Myles and Zilphia Horton, who were founders of this school. I took a couple of classes with Thorsten and learned about Highlander, its values, and the overall philosophy of nonviolent civil disobedience. At the time, I had no idea of the significant role that this school played in the Black civil rights movement, influencing icons like James Bevel, Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King.

All this training seemed like a lot of added work to slow us down. Once we got through our training, I impetuously wanted to head straight out to the nuclear power plant and start protesting. But next came the formation of affinity groups.

New recruits had to join a Crabshell affinity group. Mine had some amazing people, a couple of whom I still know. While we had all gone through training together, we still needed to meet a few times to strengthen our bonds before the action.

Together, we went over our nonviolence readings, discussions, and role plays. The organizers wanted us to be prepared before going out to Satsop and other nuclear sites. We acted out all of the steps involved in our planned actions: how to approach the gate, how to sit down and link arms, how to respond to being arrested, and generally how to treat people with mutual respect.

That approach—standing up to physically rehearse our plan—was a technique to create a body memory of what to do, and it helped to get us out of our heads. Many of us had read lots of books about revolutionary theory and history. Instead, this approach was a practical how-to. It allowed us to tap into the human level of our actions without being driven by intellectualized theory, where people can be reduced to concepts more than flesh and blood.

The Trident Nuclear Submarine base was located near Bangor, Washington, which was on the Kitsap Peninsula on the eastern side of Hood Canal. Since it was a submarine base, there wasn’t much to see unless the subs rose to the surface.

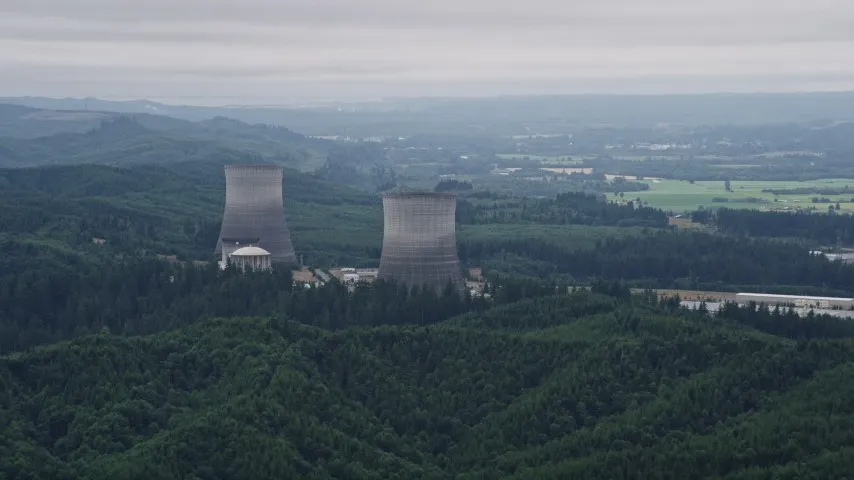

Satsop, however, was a highly visible presence in an otherwise bucolic area near Elma. The project was managed by the Washington Public Power Supply System, commonly known as “Whoops!” The surrounding area felt like occupied territory once WPPSS began construction on two giant cooling towers. I remember looking out the window while driving there and seeing the towers, visible for miles and sticking up over the trees like the Eye of Sauron tower in Lord of the Rings.

Our affinity group joined in a couple of mass actions. Once we got to the sites, things went pretty quickly. Months of preparation yielded to a rapid chain of events. As all of our affinity groups sat down in front of the gate, we were swarmed by police and company officials ordering us to leave. Waves of arrests began soon after the warnings. Then we were all loaded onto buses that took us away to be processed. Once we were processed, we’d be released to our support teams, all part of a fleet of hippie cars and trucks to ferry us home. Soon thereafter, we would hold a debrief to examine what worked, what didn’t, and what we each learned.

Every step of the way was guided by principles of nonviolent civil disobedience and mutual respect.Differing from the open warfare between activists and riot cops, we all learned that nonviolent resistance did not involve breaking windows or wrestling with the police. Having been minted in the boisterous days of the antiwar movement, the more deliberative tenor of the no-nukes movement was deeply impactful.

Our affinity group was musically inclined, so we got mimeographed copies of anti-nuke songs. These clever rewrites of familiar tunes were our no-nukes songbook. We performed them everywhere we could—rallies, fundraisers, and other events. We called ourselves something catchy like the Crabshell Chorus. We were nowhere near as good or well-known as the Seattle-based group called Shelly and the Crustaceans, but we did have our own little following.

Ultimately, Satsop collapsed due to bad management and a successful referendum requiring voter approval for any new financing. Later, when I got a job working for the City of Olympia, I learned that WPPSS had become a cautionary tale because it triggered one of the largest municipal bond defaults in US history. However, Trident was impervious to our protests and continues to the present day as one of the US military’s primary nuclear submarine bases.

Like many political movements, Crabshell Alliance faded into the background, and activists moved on to do other work. What has remained for me and many other participants was the way we did the work—using principles of nonviolence, making decisions by consensus, and respecting the leadership of women. For me, this was the beginning of shifting toward women-led political activism.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer