ARTS

Jazz in Olympia: Big Time Small Town Scene

By David Lee Joyner

Olympia? Why would anyone want to live in Olympia?” That was the response from a Seattle musician I was gigging with years ago when I told him where I lived (2000 – 2006). I discovered that it is the prevailing Seattle view of Olympia, or anywhere else in Washington, for that matter. The typical Olympia reaction is to let Seattle residents go ahead and think it’s provincial, so they won’t move there and make it as crowded and expensive as Seattle is.

I think the state’s capital is a treasure—beautiful, less crowded, economically accessible, friendly, it had great schools for my kids, and it was a convenient commute to my day gig as a professor at Pacific Lutheran University in south Tacoma. To my delight, I also discovered a vibrant community of musicians in Olympia, some of international repute and stature. Unfettered by the lack of local gigs, these wonderful artists’ activities have flourished, and they welcomed me into the fold with the same small-town warmth possessed by the city in general.

While the people and events chronicled here may be old news to some readers, to younger readers and newer arrivals, the story is an inspirational eye-opener.

Olympia Jazz Roots

Duke Ellington’s orchestra played at the Olympia Armory in the early 1940s and came back through for a Northwest tour in 1952, captured on a Folkways album, First Annual Tour of the Pacific Northwest, Spring 1952 (Folkways 02968, 1983). Olympia was an occasional stop for traveling bands during and after World War II, many working the Evergreen Ballroom, one of the most prestigious venues in Southwest Washington, seeing the likes of Woody Herman and Stan Kenton. In the 1960s, it became more of a “chittlin’ circuit” roadhouse. On Sunday nights, it presented acts such as Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and Etta James. But the real history of the Olympia scene as we know it today began in 1971 with the founding of The Evergreen State College and the establishment of Red Kelly’s Tumwater Conservatory jazz club shortly thereafter.

This establishment (1974 – 1978) became the temporary resting place for veteran jazz bassist and long-time road rat Red Kelly (1927 – 2004). Red was a prankster; his most distinguished act of local irreverence was his satirical run for political office as head of the OWL party (“Out With Logic”). Part farce and part scathing commentary on politics-as-usual, Kelly actually won a significant minority vote. Red later opened his club in downtown Tacoma in 1986.

Tumwater Conservatory also revived the careers of two marvelous vocalists. Chuck Stentz’s wife, Jan, responded to Red Kelly’s bidding and jump-started her singing after time off to raise kids. She succumbed to cancer in 1998, but her impact and influence are still felt on popular local singers. The other vocalist to make a comeback at Tumwater Conservatory was Ernestine Anderson (1928 – 2016). After a decline in her career, with Red Kelly’s encouragement, she began singing again in Tumwater around 1975 and was soon heard by bassist Ray Brown (1926 – 2002) at a music festival in Canada. Brown took on the management of her career, signing her with Concord Records.

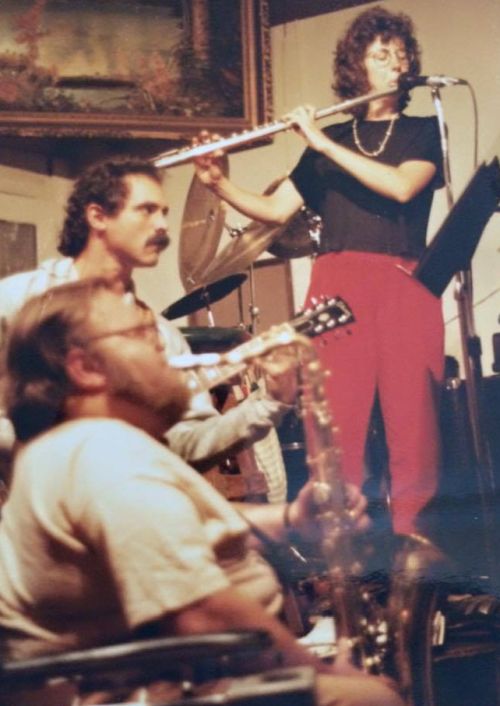

Red eventually moved to Tacoma, but there were other Olympia jazz pursuits, with the music becoming more eclectic. Much of the credit goes to the tireless work of Olympia pianist Michael Moore (1947 – 2023). Moore conceived the idea of his Latin jazz band, Obrador, at Berkeley, bringing it into being in Olympia in 1976. With the help of Eclipse Productions, Obrador performed with Charles Mingus at the now-defunct Tyee Motor Hotel in Olympia on April 3, 1977. The seven-piece band was together for over 25 years. These individuals are still part of the Olympia jazz elite.

Obrador’s music was eclectic, original, uplifting, and entertaining, but Moore and the band’s efforts to bolster artistic appreciation, freedom, exploration, synthesis, and tolerance, and their incalculable support of music and music education with their modest means have had an equal impact on the artistic community at large.

In June 1998, Obrador spent an afternoon at the Escuela de Musica del Municipo de Guanabacoa, a music academy in Cuba. After witnessing the wonderful music made by the children in the squalid conditions of the school, the band initiated The Guanabacoa Project to raise money for the school and to send it musical instruments. Obrador has been equally generous at home.

For all their longevity, Obrador got few gigs, mostly on the festival and college circuits. Like many eclectic artists, the group members were always on the lookout for a venue to play in as well as to encourage performance and experimentation in all the arts, and a place for education and nurturing in the arts. They discovered a vacant downtown office building at 321 Jefferson Street near Percival Landing. Envisioning a communal performing space along with office space for artists of different disciplines, the property was leased and remodeled with volunteer labor, donated materials, and several fundraising performances. Among the many events held at Studio 321 was a community-based high school big band, under the auspices of a jazz component of the Capital Area Youth Symphony Association, later autonomously established as J.A.S.S. (Jazz Alliance of the South Sound). It was a jazz tutoring program spearheaded by local musicians Syd Potter, Richard Lopez, and others.

BWU (Bert Wilson University)

Artistically and physically, Bert Wilson (1939 – 2013) literally played for his life. Born in Evansville, Indiana, he contracted polio at the age of five. Doctors never expected him to survive into adulthood. With lung problems, as much a chronic symptom of polio as the crippling effects that confined Bert to a wheelchair, he took up clarinet and saxophone as therapy. Early on, he was influenced by Charlie Parker and long-time Ellington clarinetist Barney Bigard. In the 1960s, he fell deeply under the spell of John Coltrane, particularly the free music of his latter years.

By 1979, he was stuck in Woodstock, New York, eking out an existence. Michael Moore, who had met Bert at Berkeley, led a fund-raising effort to get him a plane ticket and bring him to Olympia, where he remained.

Bert was a disciplined reedman, composer, and theorist. Through unique fingering systems he developed, Wilson extended the range of the saxophone to encompass six octaves, techniques he passed on to the likes of Benny Golson and Saturday Night Live’s Lenny Pickett. He was Olympia’s most celebrated national underground legend. With his uncompromising modern jazz style and sound, he rarely made formal public performances, but was known by musicians around the world, albeit those dwelling in jazz’s most inner circles.

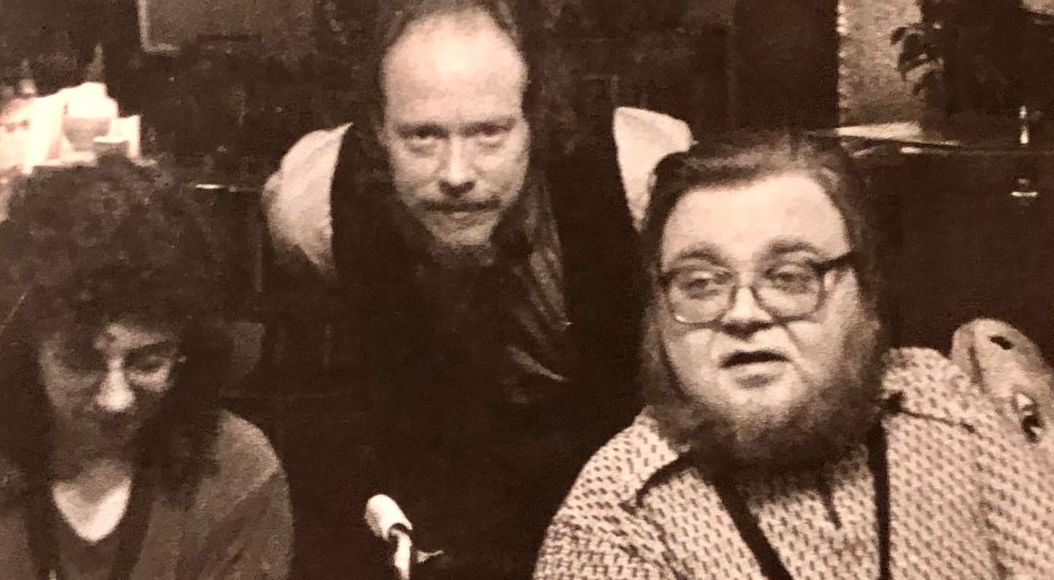

However, Bert Wilson was far from a musical recluse. When he made a public performance, it was often in the company of jazz royalty. But most often, Bert held court at home. There was no more solidifying musical institution in Olympia than the regular jam sessions at Bert’s house in West Olympia, happening almost every night since his arrival in Olympia in the late 1970s. His house was known alternately as BWU (Bert Wilson University), as dubbed by pianist Joe Baque, and The Percival Street House of Jazz. At Bert’s, the mainstream old guard commiserates with the avant-gardists and young jazz students and budding professionals who have driven all the way down from Seattle to try their wings. Bert’s two groups, Bebop Revisited with (Chuck Stentz, 1926 – 2018) and Rebirth (his ultra-modern jazz group going back to his East Coast days), reflected his ecumenical place as the axis of all of Olympia’s jazz styles.

Olympia Jazz Venues

Most Olympia-based musicians drove up north for our gigs, while the Olympia jazz scene thrived mostly behind closed doors.

After the demise of the Tumwater Conservatory, the next bright spot was the Gnu Deli, which peaked around 1979 – 1980. The Gnu Deli promoted modern jazz and hosted notable artists of that genre, such as Anthony Braxton, Sam Rivers, Woody Shaw, Mal Waldron, and Leroy Jenkins.

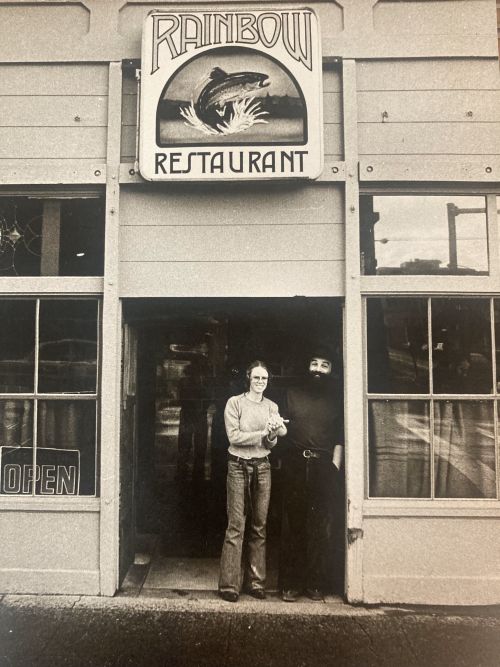

The Rainbow Restaurant on Fourth Avenue was a jazz stronghold owned by Andrew and Laura May Abraham Booker, themselves musicians. Local musicians played there regularly on Wednesday nights, and between about 1975 and 1983, the venue hosted nationally known jazz artists such as Joanne Brackeen, Ralph Towner, and Don Cherry.

One of the most cherished jazz venues in the memories of the local musicians was Barb’s Soul Cuisine, owned by Barb O’Neill (1936 – 2008), who worked for the state Employment Security Department. Barb’s Soul Cuisine was a tiny place across the street from the Rainbow Restaurant. Running on a shoestring budget, Barb had music most every night in the 1980s, often paying the performers out of her own pocket.

The most stable jazz venue in Olympia was the Spar, a venerable downtown diner and tobacconist on Fourth Avenue dating back to the 1930s. There was jazz in the bar every Saturday night. In spite of the smoke, there was no crowd in any city of any size more appreciative or hip than the audience at the Spar. I know that many of my mountaintop experiences have been performing there. Alan McWain was also a tobacconist (hence all the smoke in his establishment) and, when the state and the nation passed laws prohibiting indoor smoking in public places, he sold the Spar to the restaurant and microbrewery chain McMenamin’s. The Spar was remodeled, and live music was dropped.

Other contemporary Olympia venues that showcased jazz occasionally are the Limelight (formerly Thekla) at Fifth and Franklin, Ben Moore’s Restaurant on Fourth Avenue, just west of the Spar, and Traditions.

Bands and Artists

There were many notable bands and artists in Olympia, some established ones I’ve already mentioned, including Obrador and the members therein. Mention should also be made of trumpeter Barbara Donald (1942 – 2013). Cited by Scott Yanow of the All Music Guide to Jazz (www.allmusic.com) as “one of the top female trumpet players of all time,” Donald was prominent in the 1960s and early 1970s. The album Olympia Live (Cadence CJR 1011) is the All Music Guide top pick for her recorded oeuvre.

The bloody banner of Olympia jazz is being waved by local artists with an average age span from about 45 to 80 years old (though there are a few younger up-and-comers). They came to Olympia at a point in their lives where they wanted to come off the road, get out of the New York rat race, and continue their craft in a laid-back and comfortable environment. They retain the artistic passion and intensity of the experience of their youth, still commanding awe and respect from audiences and other musicians. Now, the search is on for young, talented jazz locals who will carry on in future years. Some may be gestating in Olympia right now. Perhaps urban sprawl from Seattle will make its way that far south and increase the number of promising future artists. Whatever its future, for now, jazz in Olympia is alive and well.

*****

David Lee Joyner is a pianist, composer, vocalist, educator, and writer. He was Professor of Music at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma and has performed with major celebrities.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer