ACTIVISM

Blossom Patches

By Pat Holm

Around 1970, Steve Wilcox and a group of friends decided to lobby for the legalization of marijuana. We formed an organization called BLOSSOM: Basic Liberation Of Smokers and Sympathizers Of Marijuana. I was the sympathizer since I didn’t smoke pot and nobody was doing edibles yet, except for the occasional fibrous brownies. We wrote up a list of ideas, goals, and tasks, and we assessed what each of us could contribute to the effort.

Steve and I met with a legislator, Peggy Maxi, and a Seattle lawyer, Tom Gayton, who were interested in the idea of legalizing pot. These two were from the Central District in Seattle—the bulk of the 37th Legislative District and the main African-American neighborhood of the city. We were all concerned about the number of young men, especially young Black men, who were going to prison on minor possession charges, sentenced like they had committed serious felonies, and who ended up trapped in the criminal justice system.

I had been working as a researcher for the Department of Corrections keeping statistics on adult felons for quite a few years and I knew the prevalence of this racial injustice surrounding marijuana convictions. Progressive Black legislators like Peggy Maxi were interested in changing the laws. In Washington state the legislature meets for just a few months out of the year so when Steve and I had our meeting with Maxi in 1971, there really wasn’t enough time for a bill to go through the whole process. The effort that year was short-lived. But the idea got some traction.

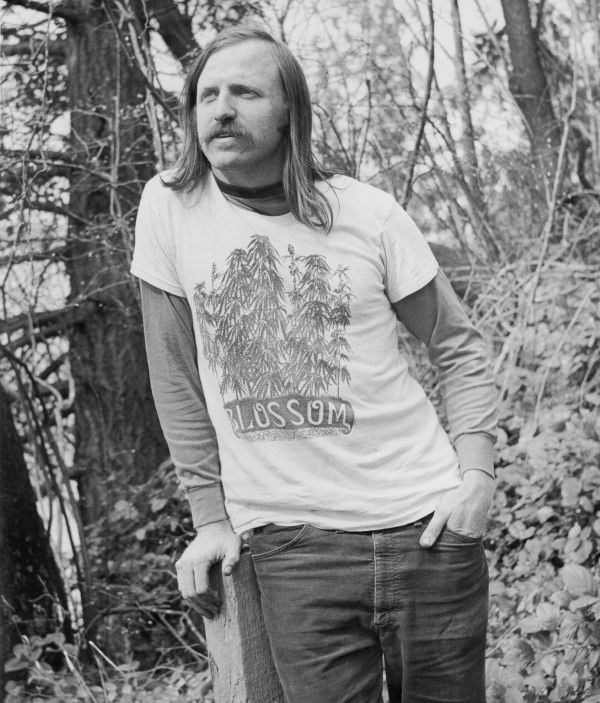

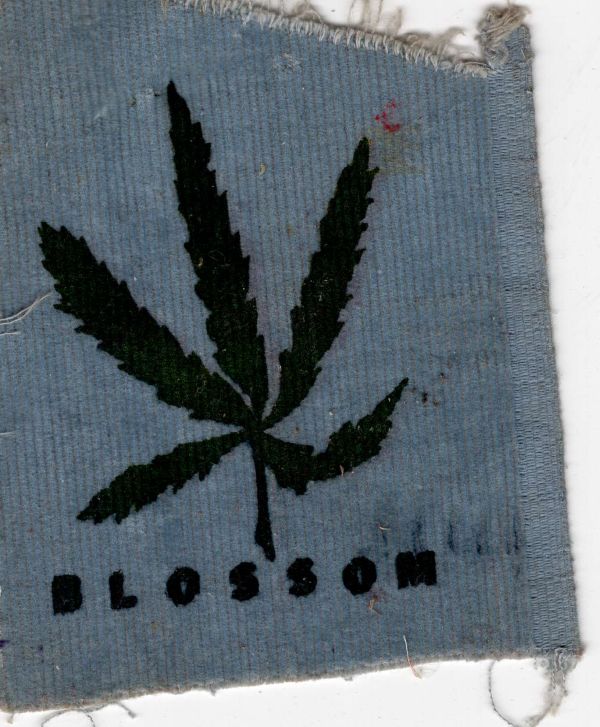

Steve and I moved to Giles Road in May 1971. Our neighbor, Bob Gillis, was a friend of mine and a local artist. He designed silk screens, and we had a place in our house to do screen printing. We put up some tables in the basement that we could leave up. Bob and I came up with three basic designs of a logo for Blossom and for a series of promotional images. For example, we sold individual blossom patches. It was a way of identifying like-minded folks and making a little money for the cause from small contributions. People would sew the patches onto their clothes. In my case, since we printed them in our basement, I screened them directly onto my clothes. Or if folks wanted T-shirts with one of the designs we could print them a shirt with the design of their choice.

A few years later when a rock festival, called Satsop River Fair and Tin Cup Races, was held near Elma, Steve and Thom Abbott went with their silk screen equipment and printed blossom patches onto women’s breasts. The guys had a lot of fun, but I was a bit jealous of Steve’s fondling of all of those young women’s breasts. The festival was a rainy, muddy event, so I was glad I opted not to go.

This whole BLOSSOM enterprise went on for quite a few years. It took decades to change the laws. Starting with Oregon in 1973, individual states began to liberalize cannabis laws through decriminalization. California became the first state to legalize medical cannabis, sparking a trend that spread to a majority of states. Washington and Colorado were the first states to legalize and tax cannabis for recreational use.

I was surprised to learn from my journals that we had four legislators meeting with us in that first couple of years when we started advocating for legalization. Besides Peggy Maxi, there was Mike Ross (a Black Republican), Pete Francis, and Dick King, who was a fellow Unitarian and a legislator. I believe Pete and Dick were both from the Snohomish area. Mike Ross advocated for the decriminalization of cannabis in 1971. He was elected to serve the predominantly Democratic 37th District. During his term in office, Governor Dan Evans appointed Ross to the state Law and Justice Planning Committee. Despite his style of working within established political channels, Ross didn’t shy away from controversy. The bill he introduced failed, but It is believed to be the first bill to legalize the recreational use of marijuana, four decades before the drug was ultimately legalized in Washington.

At some point, Thom Abbott went to Washington D.C. to attend a meeting of NORML (National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws). Three states were present in those early days: Washington, California, and Michigan. A report submitted to Congress by the National Institute of Mental Health concluded that, based on various studies, marijuana is not addictive, that it cannot be shown to be physically or physiologically harmful, and that its use does not appear to lead to hard drug addiction.

Note: In summer of 1971, President Richard Nixon began what he called the “War on Drugs.” The Republican party took up the “war” as a major plank in their platform. Any candidates who opposed it were labeled soft on crime and it became nearly impossible for states to consider decriminalization or legalization of marijuana because it was a federally-classified dangerous drug. It was later revealed that Nixon’s administration was conducting a massive drug operation involving the US military in Southeast Asia and flooding inner cities in the US with heroin and cocaine.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer