SCHOOL

Part 2: Joining the Faculty at Evergreen

By LLyn De Danaan

(Continued from Part 1: Finding My Place in the Universe)

The campus was mud and machinery with a few pillars of concrete here and there. Staff and deans were in trailers on the property. The scent of something grand was in the air.

***

Merv Cadwallader liked me and wanted me on the faculty. I sat across the desk from him in his humble trailer office and listened to his vision. He said he wanted anthropologists, not sociologists. His hair was gray and was combed forward in what is called a Brutus cut. He looked like a cross between depictions of Julius Caesar and a monk. If he had his way, we faculty would all have been leading monkish lives—cloistered on campus, literally full-time mentors and teachers. One had to be willing to give one’s life to this enterprise. It was he who brought the idea of coordinated interdisciplinary studies to Evergreen. It was he who wanted a spring renaissance fair with choral singing, the celebration of student accomplishments, very ancient Greek or Californian or both. That event morphed into a Super Saturday public relations event. Someone else’s dream. Most everything morphed over the years.

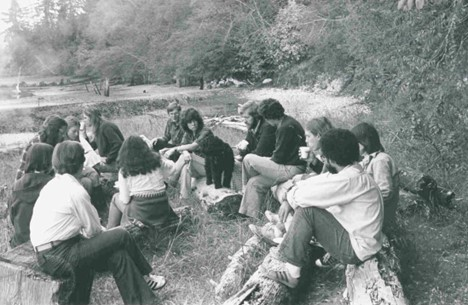

I was invited to a Pack Forest Conference Center retreat. I believe it was the spring before our opening in the fall of 1971. I knew no one other than Carolyn Dobbs. I had encountered her at UW and she was on a trip with some of us to Delano to join the United Farm Workers protests. The retreat was for newly hired first-year faculty, deans, and, probably, other administrative staff. Women faculty were in a cabin together. The cabin had bunk beds with thin mattresses and few, if any, other amenities. I was fine with that because I’d lived in farm labor camps over the previous two summers and had slept many a night on split bamboo floors. I was pretty tough and gritty. The only woman in the cabin with whom I felt an affinity was Mary Ellen Hillaire. We sat at a picnic table on a little porch attached to the cabin and talked.

Willie Unsoeld led us on some rope challenge, a test of our mettle or courage or trust I suppose. Willie had achieved fame for his Mount Everest climb in 1963. He had also been a staff member with the Peace Corps in Nepal during the same time I was in Sarawak. I learned that some of the male planning faculty did not care for Willie. He had led them on a grueling and precarious mountain journey and scared the wits out of several. I had, coincidentally, seen Willie on a boat trip on Lake Chelan a summer or so before, but didn’t know then who he was. I had watched young people gather at his feet as the boat, The Lady of the Lake, chugged toward Stehekin in the North Cascades. I noticed his signature hat. It seemed he was a heroic character of some sort, a storyteller, a bigger-than-life fellow, with a silent spouse at his side. And here he was at my first Evergreen gathering.

At the retreat, I was partnered with Richard Alexander, Steve Herman, Richard Brian, and Ted Gerstl and tasked to plan and coordinate a new, upper-division class we would call Human Behavior. The planning faculty had not prepared for transfer students, but there were many. Something had to be cobbled together for them. Richard was a tall, imposing redhead who talked a lot about his southern background and education. Steve, an ornithologist, introduced me to the poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Richard Brian could teach math to anyone with only a pack of frozen peas as a prop. Ted was an endearing, sometimes silly fellow, and psychologist with whom I loved playing pranks and enjoyed debating substantive theoretical issues in our work, egged on by panels of students. We worked out a book list and themes and had a wonderful year. Our faculty seminars were exquisite. I remember one seminar on Doris Lessing’s The Golden Notebook. We knew how to be colleagues and grow with our students. I loved these guys and we remained friends. Ted and I were younger than the others by several years. Yet I, an uppity woman, was put in charge of the nitty-gritty of the program. The only and first woman coordinator of a program.

We had no offices at first. The buildings weren’t ready. So, a solution that became a model for programs for years after was born. We retreated to Sun Lakes State Park in Eastern Washington near Coulee City. We loaded vans with food and sleeping bags and projectors, films, books . . . five faculty and nearly a hundred students.

We must have been mad. We hadn’t learned yet how to organize a program . . . we didn’t know what a program was! And yet we were off for a couple of weeks as if we knew what we were doing. One of our first tasks was to group the students into seminar cohorts and help them get to know each other. I can’t recall how we cooked. But people weren’t as picky then, so we somehow pulled it off. I do remember that Richard Alexander screened my favorite film at the time, The Night of the Iguana. We traveled to a local pub several times and I played my favorite song at the time on the jukebox, Help Me Make it Through the Night. The pub ran out of beer, unaccustomed as the owners were to such an onslaught of customers.

We were able to enter the campus buildings after two weeks away. We had seminar rooms, but students quickly covered fluorescent overhead lights with gels or tissue because, of course, fluorescent light would make us all sick. There were few established rules, so our first big scandal was born: dogs attended classes. The local papers made a thing of that. Dick Nichols, the campus PR jockey, thereafter scrutinized photographs to go out to the public for any suggestion of a dog. Doors hadn’t been hung on our offices yet. I constructed one from a cardboard refrigerator box and cut an arched opening that I and others had to crawl through.

I lived in a log cabin on East Bay Drive for part of that first year. I soon went crazy in that dark wood structure with only my Seattle cat, Portable, for a companion. (Portable attended seminars held in my house.) We (the humans) could talk for hours about a book. That’s all we did. That was the idea. No schedules, no clocks, nothing but digging into books and ideas. And potlucks. Lots of brown rice.

My brother, Judo, and his little family moved to Olympia when I did. Judo enrolled in Evergreen’s first media program and had a radio program on KAOS called The Ivory Brother. The family rented a house in east Olympia at first, then moved to rural Sleater-Kinney. He fished part-time with his father-in-law, a Ballard fisherman. As he had done before, Judo lost interest in academic life. He met two other Evergreen students, Mike Saul and James Koons, fellows with money. Together, they launched a kayak school and rafting company on the Rogue River in Oregon. Judo lived on a bench in their garage with his 45-rpm records and a stack of treasured comic books. He is still on the Rogue, though not on a bench, and he still fishes. Before he left, I lived with his family on Sleater-Kinney for a while to escape that lonely East Bay cabin.

I soon found a better, more grown-up place to live in Olympia. Friends and fellow faculty, Ida Daum (aka Ida Tafari) and Naomi Greenhut (aka Bonnie Alvarez) rented a big Victorian and had room for me. Ida was a biological anthropologist whom I knew from activist stuff in Seattle and Naomi was trained in a branch of neural science and was a dedicated revolutionary of some stripe. The house had few rules but we were to be home every Thursday eve for Naomi’s chicken soup. Naomi and Ida left Evergreen fairly early on, Ida to Jamaica where she became a Rastafarian—much honored at her passing—and Naomi with partner Claude to full-time politics.

I learned to be even more resilient and quickly adapted to their quirky ways. They wore thrift shop fur coats and sat at a card table in front of the blazing fireplace to prepare for the next day’s classes. They invited assorted people to come to stay or move in. Once it was a circus troupe. Once it was a fellow who had taken a vow of silence and wrote little notes to me. Once, it was a French hitchhiker named Claude. He was allowed to stay permanently in exchange for cooking our meals. He and Naomi had a child together and lived as a family after she left Evergreen. One visitor later joined the faculty when I urged her to apply during my academic dean years (1973 – 1976). I managed to interview her in Buffalo, braving a massive snowstorm, while I was in the east doing a series of prospective faculty interviews. Her name was Joye Hardiman. Maxine Mimms, who was her friend from Seattle activist days, and LeRoi Smith were regular visitors. Maxine and LeRoi were Evergreen faculty members.

I was ready for my own place and the next chapter of my life after a year or so. In 1973, I became an academic dean, Evergreen’s first woman academic administrator, and I bought a boring ranch-style house on Decatur Street in Olympia. That would not do. Naw. I met Marilyn Frasca, who was hired by Evergreen, and, with the aid of estate agent Doris St. Louis, found us a moldy, run-down, blackberry-choked house on Oyster Bay. Marilyn and I moved there and she started knocking down walls with a sledgehammer. It was an effort to modify the cramped floor plan.

Maxine bought the place next door with a couple of partners who soon realized they were not cut out for our decidedly “alternative lifestyles.” Maxine bought them out and Marilyn knocked down one of her walls. Susan Christian bought the defunct Brenner Oyster Company buildings below us. Soon, faculty member Craig Carlson, a William Blake enthusiast and faculty member, put up a Lindal log home on adjoining property. He gave me white frizzle chickens to add to my growing menagerie of poultry and rabbits. He gave me a couple of apple trees that he subsequently uprooted after a row with me. His goat, Jerusalem (also a Blake devotee), trotted around the neighborhood eating everything we planted. I grew to loathe the sound of the bell on its collar.

Cappie Thompson rented Maxine’s place as she forged her career in the fabrication of fabulous glassworks during the early days of Mansion Glass. She drove to Cold Comfort Farm to enjoy Richenda and Bill Richardson’s wood-fired sauna. Their shop in town, Childhood’s End founded in 1971, was in its infant stage. Others circled the fringes of this crazy life. Some stayed for a bit, most moved on after a short residence. Joye Hardiman had a tepee pitched on my drain field one summer. It was all fitted-up with exotic rugs inside. I hosted a feminist summer camp one year for philosopher Marilyn Frye and her partner, along with Hollis Giammatteo, a writer who had, in the interest of peace and with a group of Seattle lesbians, walked the route of the white train that carried nuclear weapons from Amarillo, Texas to Bangor nuclear submarine base in Washington. Chelsea Bonacello was a visitor. She shingled and painted Maxine’s house. Jean-Vi Lenthe, who sometimes performed her poetry with Noh Special Effects at Carolyn LaFond’s coffee shop, Intermezzo, was here and there. As was Moon Beam, who lived in a painted caravan somewhere on the westside of Olympia. Relationships were sometimes intense and fraught. A woman who later became an Evergreen board member referred to us as “the Valley of the Dolls.” It was not a compliment.

However, it was all very brave. And we endured. Susan, Maxine, and I are still on Oyster Bay, side by side. Cappy and Marilyn still own property up the hill. Many have come and gone. Some will be here as long as we are able. A community, not a commune. An effort. A truly remarkable shared life.

We encourage readers to contact us with comments and corrections. Disclaimer